How did you find your way to a craft such as a tapestry weaving? Is there someone who introduced you to it?

The answer to this question can be traced to when I was 15. I had a dream of becoming a photographer, we even had a darkroom at home but my parents were getting a divorce at that time and the darkroom went with their relationship. Therefore, I lost the base for my interest and my parents decided it wasn’t the right path for me anyway, practically discarded my dream and came to the conclusion I’ll be better off as a weaver, as I had the dexterity that would go to waste should I become a photographer. So, the decision that this half-dead, half-existent craft was the most suitable was made by my parents. (laughter) Both my parents have a creative and artistic background and a lot of friends involved with textile crafts and, coincidentally, a new field of study called Handicraft Textile Processing opened on a local high school of applied arts and crafts.

The school itself doesn’t exist anymore as it was closed in 2007 but it was excellently equipped. It was focused on folklore and design, offering folk costume and scenic costume design classes and such but my field of study was purely tapestries and their history. The practical parts, i.e. weaving, were led by forewomen from the renowned Moravian Tapestry Manufacture in Valašské Meziříčí, Czechia. My first year was driving me up the wall as I had no idea what I’ve gotten myself into and how it’ll be useful in the future but I realized only after finishing my university studies that there’s meaning in going back to textile crafts and that I’ve learned an important and immensely valuable thing.

Do you think there’s a future for traditional Czech handicrafts such as lacemaking, bobbin lacemaking or weaving? Can we expect a renaissance with the new generation?

I’m afraid I can’t give a definitive answer that as the future role of traditional crafts is a complex question but, the way I see it, there are two issues I’m noticing recently. One is the upcoming existential generational exchange that has to happen for the craft to stay alive, the textile factory owners and craftsmen and craftswomen are looking for successors and apprentices so now we’re basically waiting if there’ll be some young people to take up their mantle – the exchange is already slowly happening and it’s important to support this upcoming generation. The schools also try to attract students by relabelling handicrafts as design that could, in my opinion, help the craft survive but somehow devoid of the tradition it’s rooted in.

And the other thing is how vocational and high schools approach the handing down of crafts because, back in the day, it used to be a social, domestic and community thing – people gathered and learned from each other. I also think that our parent’s generation was raised at the brink of consumerism – they were used to austerity during the communist regime and then, suddenly, everything because more available so there was no need to endlessly mend clothes or to produce them, which also applies to handing down crafts that might have been perceived as obsolete – with honourable exceptions. That’s OK in my book, it’s a process but the result was that a lot of the kids in our generation didn’t grow up around embroidery, knitting, crocheting and such. I also think that the increased mechanization of production in all fields and the prevalence of sedentary office jobs will drive more people towards manual work and crafts.

How did the collaborations with other artists come to life?

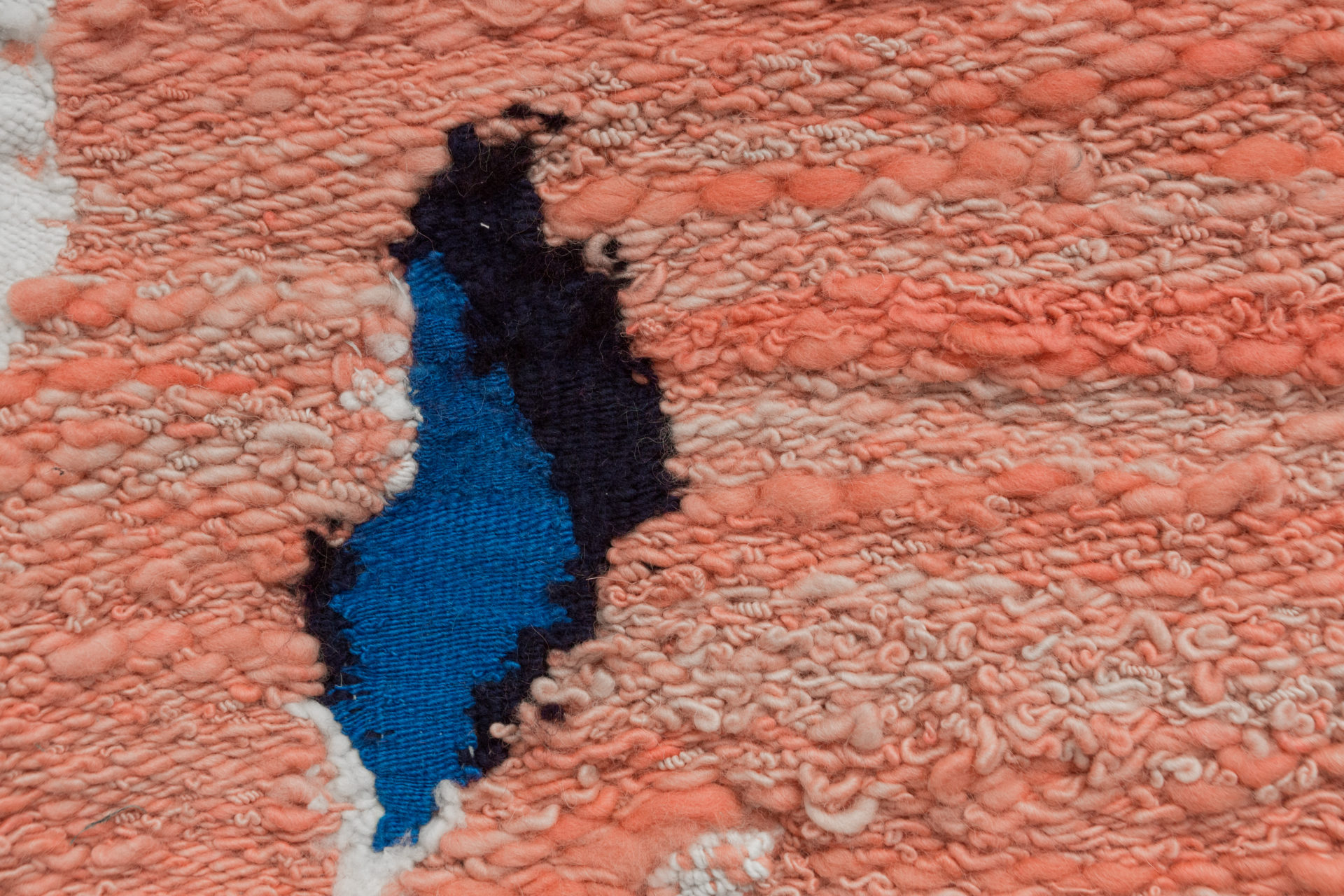

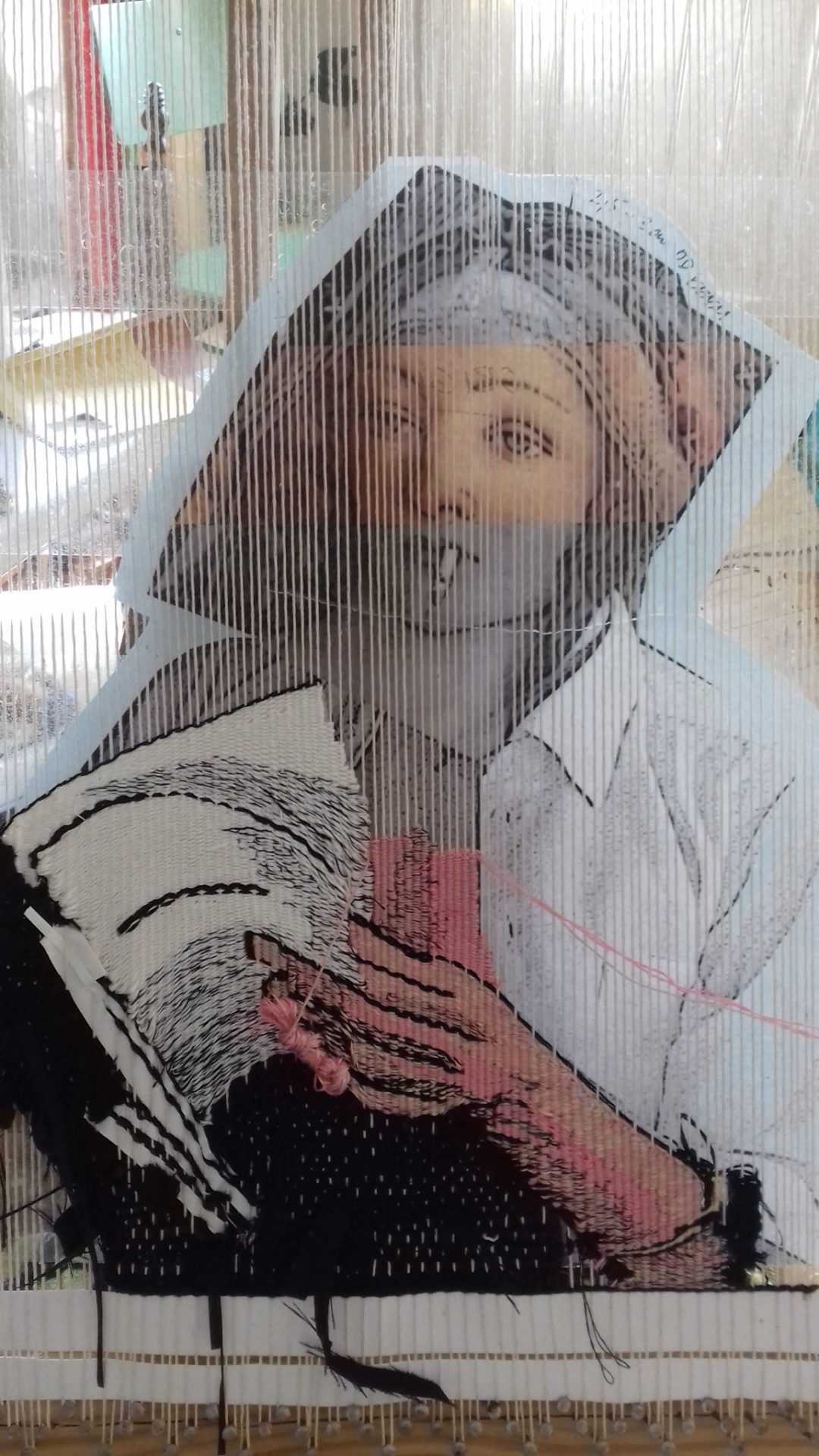

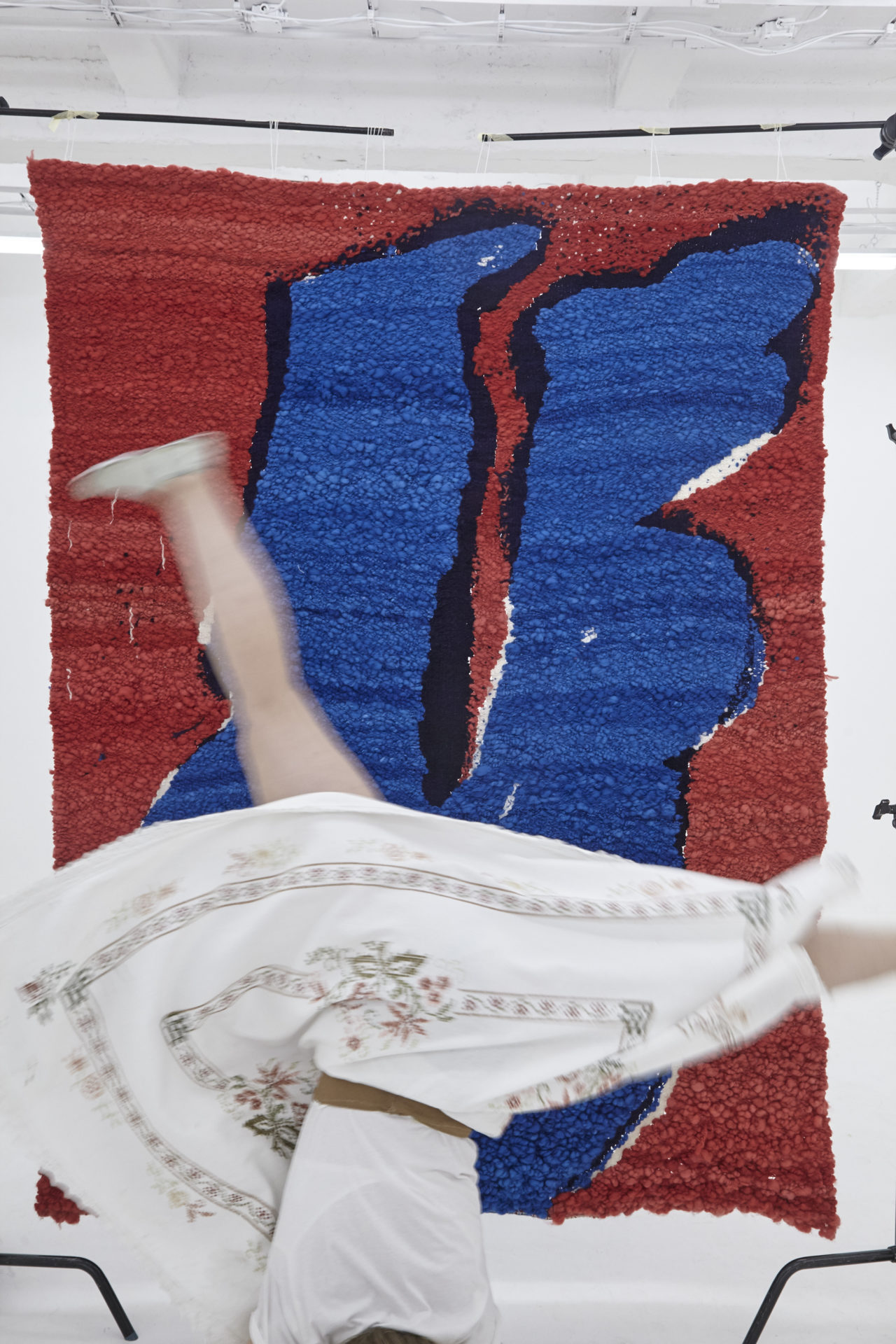

Either I contact them or they approach me. Painter Martin Lukáč was the first experimental crack at a collab. I approached Martin with the offer of creating a tapestry and he was happy to participate. We designed two pieces and as it was my first project, I wanted to go back to my roots, to Valašské Meziříčí to create them. But the manufacture has their own terms – they refuse textile designers and only want to collaborate with artists but artists of the younger generation don’t usually know there’s this possibility. Even if they do, the road to the finished tapestry is long (from one to up to three months) and quite costly, especially the finances are a dealbreaker. That’s why I think contacting Martin first was really efficient. We involved students in the weaving process, to lower the costs and, for me, it was THE project where Martin and I started to learn as the new generation. For a great weaver to master the craft, it takes about five years of daily practice so we really just started learning how everything comes together. As for the finished project, I’m extremely satisfied with the result that has both the artistic and the craft value and is the testament to the importance of the harmony between the craftsman and the artist. You can even trace our progress from a classic gobelin to a tapestry and more creative types of weaves, you could liken Martin’s pieces to a kind of improvement diary. The girls who helped me even learned how to spin yarn on a spinning wheel and, in the end, it took about two years to perfect the thread but we’ve used them all anyway.

At the start, we made imperfect but effective yarns that gave the gobelin its lively and dynamic form and as we improved, we were able to spin a thread that wasn’t accidental and became technically perfect. Both ways, the imperfections and technological quality are essential for mastering the craft and the resulting product. Thanks to the project with Martin, Czech fashion designed Klára Nademlýnská subsequently asked me for collaboration and I have more planned out in the future.

Your Prague studio is called WNOOZOW – what does it mean?

Well, I can’t really find the original source but when I was about 16 or 17, I’ve read a manga where Wnoozow was a Japanese princess of some kind and I’ve used that nickname back then at the dawn of online chatting and it stuck with me. And as I’ve never managed to track down the manga as a proof, it might have as well been a dream.

Do you think that tapestry is perceived as art by the general public rather than a soft furnishing?

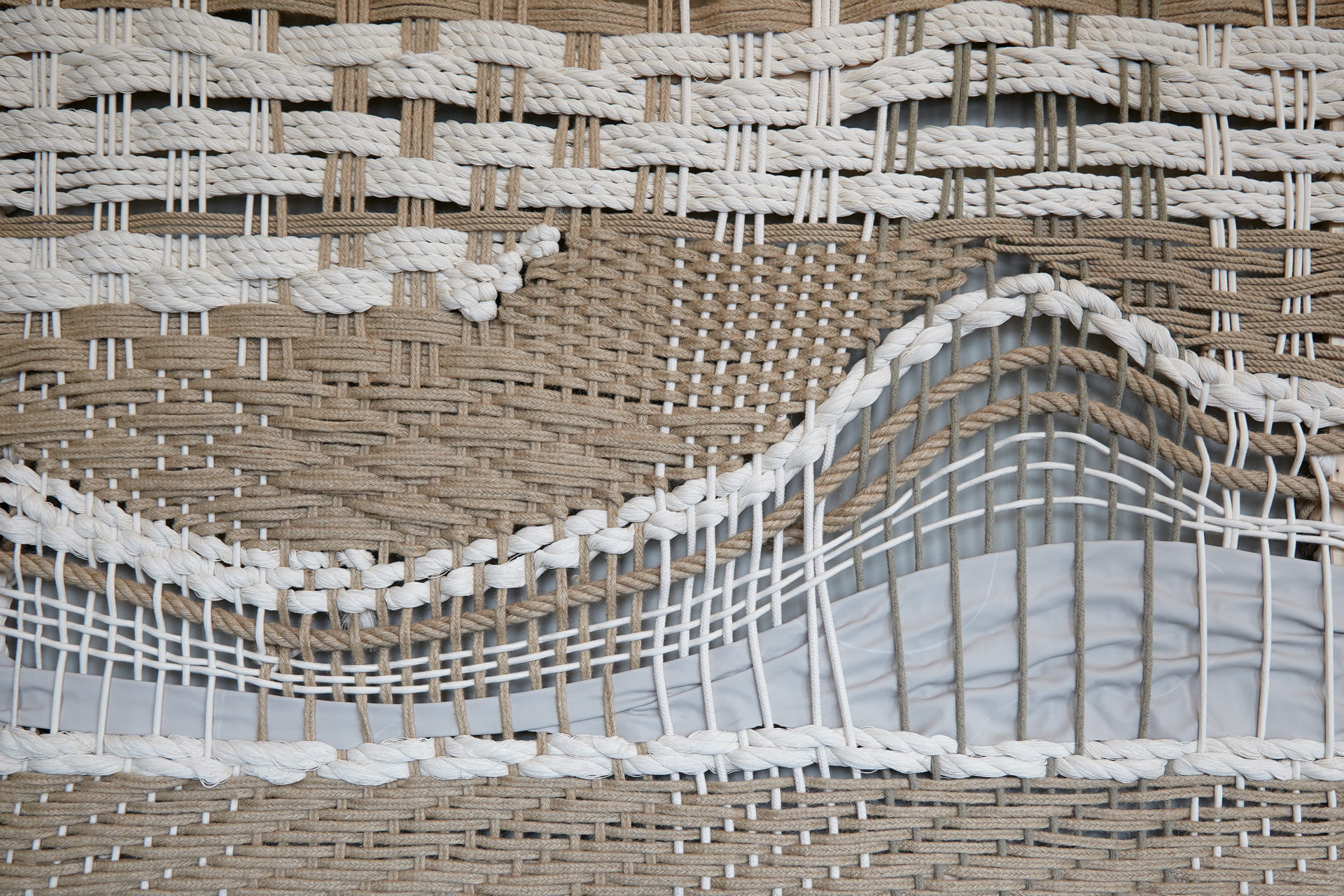

I live in my own bubble of textile art, if you ask anyone within it, the answer is evident. I did a kind of a survey once, among the masses, and most people were surprised that tapestry still exists and that it had left the walls of castles and chateaus and has been transformed into new forms. Regarding terminology, a tapestry is an umbrella term for hanging woven textile art and gobelin is one specialized branch of it that started in Paris in the 16th century and now it’s only made in Valašské Meziříčí but the general public could call even a macramé hanger a tapestry.

What do you think about preserving and passing on of such region-specific (textile) traditions, should they stay within their place of origin and be a true heritage or spread in any direction in order not to go extinct?

This is a very fresh issue that still resonates because if we take Valašské Meziříčí, the gobelin tradition practically hasn’t changed since 1898 when they started. The current director is someone who’ll never let the tradition outside of the walls of the institution and doesn’t let in any new weavers or textile designers and claims that the quality of gobelin production has degraded in Czechia during the last century because of modern influences. Once the owner of the Valašské Meziříčí manufacture told me that the weavers working for him somehow gain the historical skill and insight over the years, that you can almost see the change as if they were living multiple lives, that’s fascinating. The gobelin is treated as an artwork, starting with the motive selection and its “transcript” and ending with the appraisal. I’m a bit conflicted in this situation and even had a little back-and-forth with the director about the natural lifecycle of gobelins’ production. We can see that globalization kind of undermines the notion of tradition and its survival and the sense of national identity and has a tendency to degrade or appropriate cultures. But, on the other hand, you would hate for the tradition to die in a museum. Right now, I’m meditating on how to go about it, to not to bastardize the tradition and honour it at the same time. I would say that you don’t necessarily need the heritage to learn the craft but you should take the whole package – learn its history, roots, and purpose, create a connection and appreciate it.

ABOUT THE WNOOZOW STUDIO / Daniela Danielis is the founder of the WNOOZOW label, which is a textile and tapestry workshop. The label is established on the art and craft market since 2016 and managed to build up a name that’s recognized both in Czechia and Slovakia. The main focus of the workshop is weaving of gobelins, tapestries and handmade fabrics tailored to the needs of prominent artists and textile designers. The label picks up the historical threads of gobelin making that have more than a 120-year-old tradition in Czechia. Tapestry weaving is a technology producing artworks that are regarded as an artistic craft of the highest quality. The material for each piece is chosen individually and uniquely and is locally and sustainably sourced. It’s also hand-processed from the start, from spinning the yarn to hand-dyeing it with natural or certified artificial dyes. The weaving itself is done by experienced weavers who majored in specialized weaving fields of study. The label’s subsequent activities are courses for the expert public, student groups or designers. WNOOZOW did a prominent collaboration with fashion brand NEHERA and participated on a collection, which was presented at Paris Fashion Week in 2018. The collection was a success and soon being sold in Japan. Another significant project was a collaboration with contemporary painter Martin Lukáč, called That Time in Vigeland Park, that was displayed in the building of the renowned record label LOVE THEM. Last but not least, another mention-worthy collab was with Czech fashion designer Klára Nademlýnská that yielded three gobelins created for the label’s 20th anniversary, which were then inserted and/or transformed into clothes. One piece was bought by a private collection in New York.

Weaving / Daniela Danielis

Gallery & Tapestry gobelins / Martin Lukáč

Interview / Františka Blažková & Markéta Kosinová

Translation / Františka Blažková

Photography / Lucia Kuklišová – Gallery & Tapestry details // Matěj Visczor – Weaving loom // Danila Danielis – Archive pictures