TEXT BY ALEXANDER LEPIANKA / As the night kicked off, the guests weren’t intending to explain themselves. They were unconcerned with making sense of their self-assembled fantasy of music, powders and smoke, of their minor dramas and ceremonies of pleasure-taking. Yet, the party had found itself in a curious setting—not in its physical environment so much as in the presence of a sonorous antique. In the wake of their fourteen-hour encounter, the guests circulated images and video clips that begged the question: what had happened there? Where had they been?

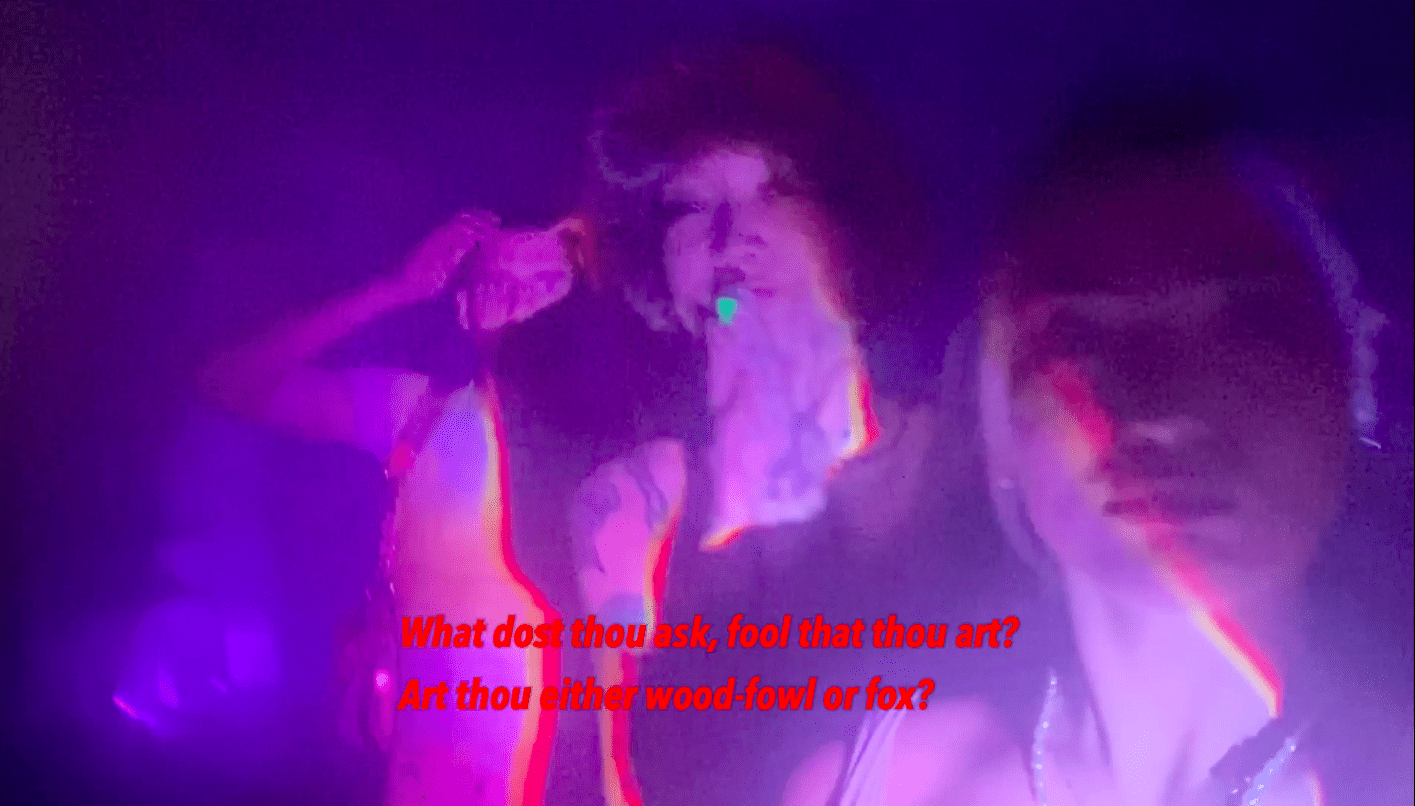

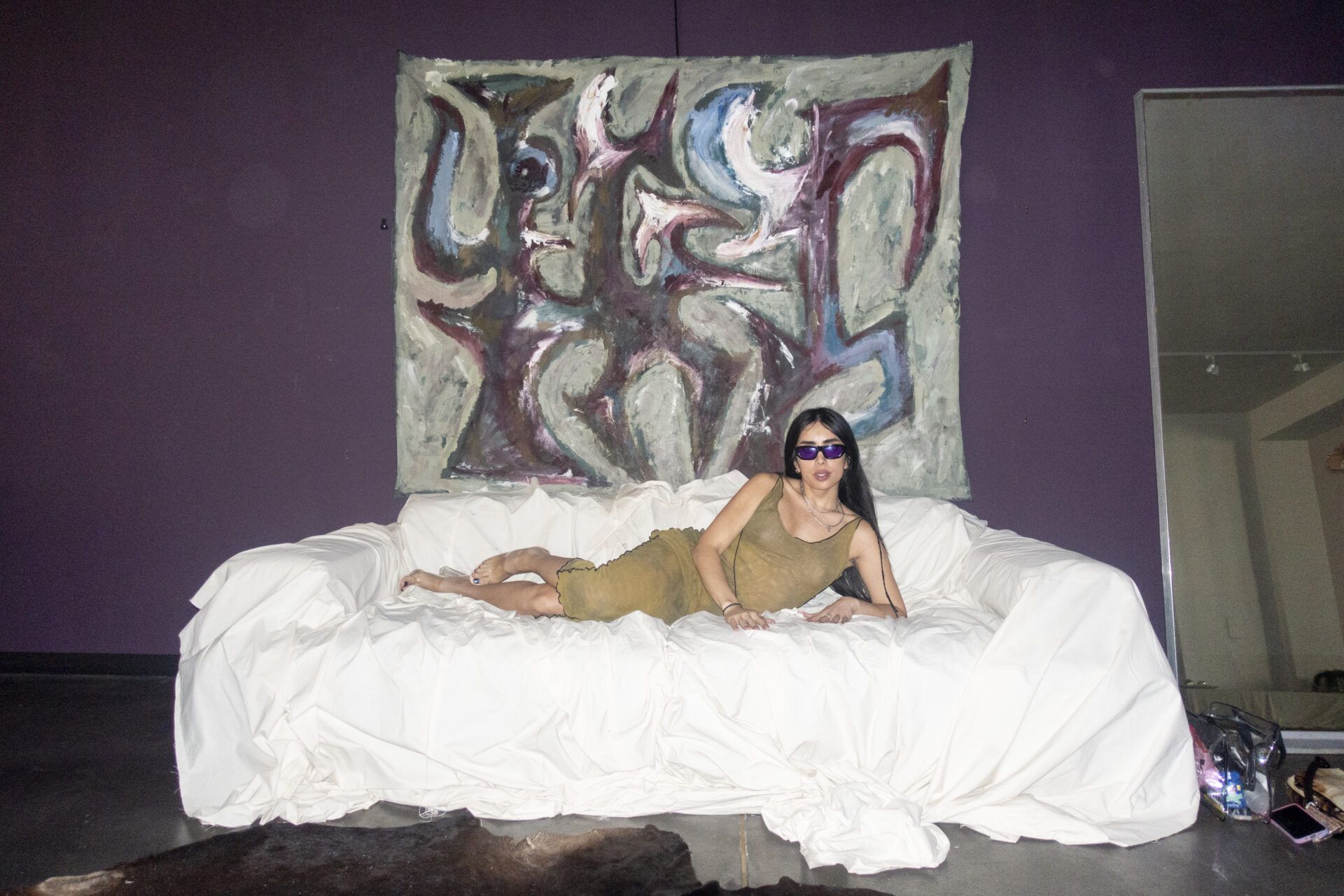

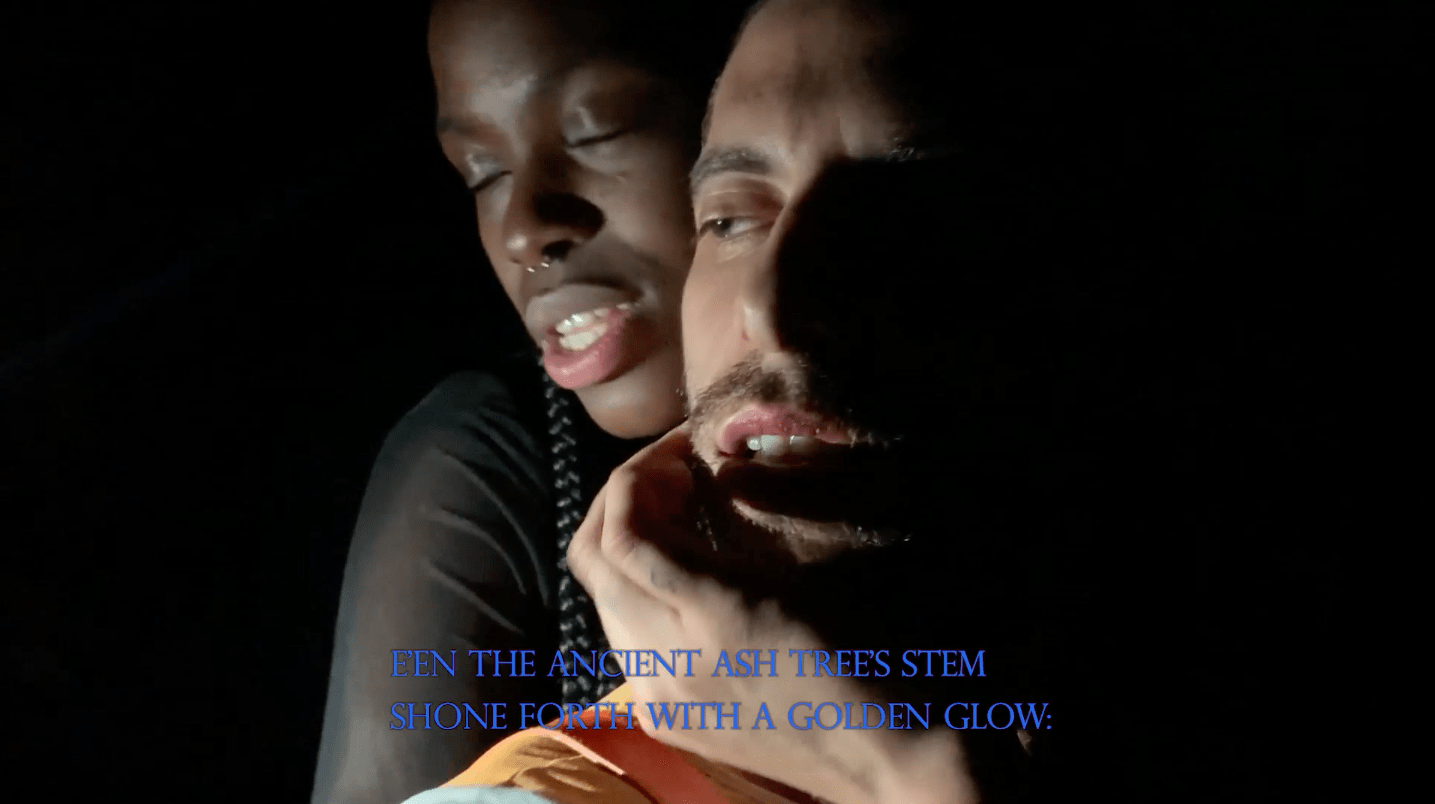

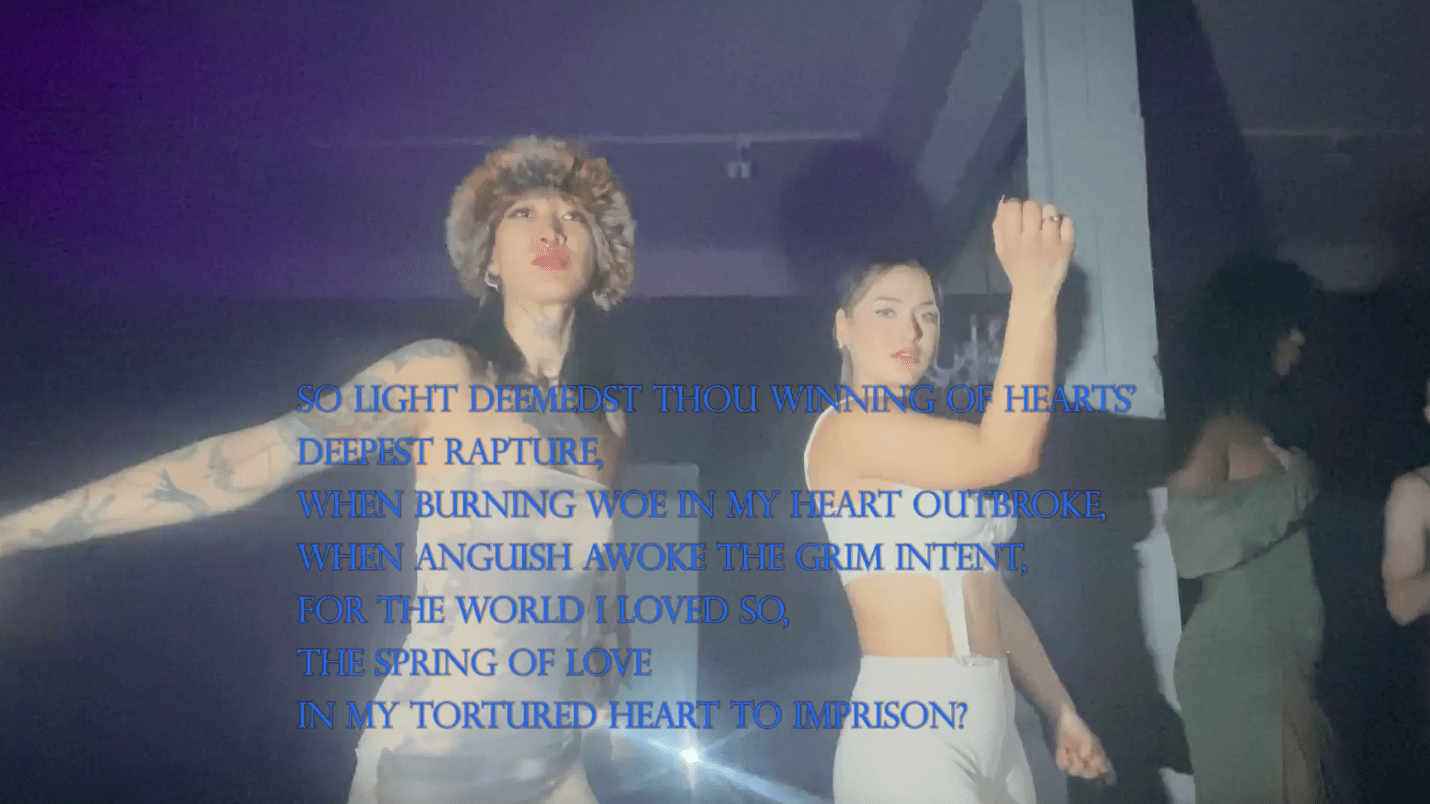

As participants of Alexander Fahima’s The Rules of Attraction, the revellers were the uninvited guests of Richard Wagner’s opera tetralogy, Der Ring des Nibelungen. Produced in March, 2021, for the Berlin Volksbühne’s digital performance series, Next Waves Theatre, Fahima’s opéra concrète exists somewhere between house party, live performance, video stream, and mail art. As a video work, the film follows a party in real time, filmed with sparse directorial cues on the participants’ smartphones but with its soundtrack and subtitle text taken from the original opera. Frame by frame, the libretto imparts meaning to the scenes. At times, the scenes suggest teasing enactments of the drama, but Wagner never dictates the content of the performance. Only at a few points—for example, a solo by performance artist Steph Quincy or an action painting by artist Mauro Ventura—does the camera cease wandering with its operator’s attention. But, even these moments are self-directed responses to the camera’s surroundings. As night rolls into day, the opera stays open to improvisational, vernacular forms of participation—in short, a party.

On one hand, The Rules of Attraction’s formal openness makes reference to contemporary public-participatory art, namely to the work of the British artist Jeremy Deller. Fahima’s use of party as medium resembles Deller’s Procession, a work conceived for the 2009 Manchester International Festival that took the form of a parade, celebrating the diversity of the city’s occupants: Unrepentant Smokers, The Last of the Industrial Revolution, Carnival Queens, and so on. Fahima also shares Deller’s concern to wrest open a national tradition or heritage, making it hospitable vernacular use.

However, Fahima’s work is deeply historical in its scope, “squatting,” to use the artist’s term, both Wagner’s opera tetralogy and the heritage it symbolizes. While the participants were informed about Fahima’s project and exposed to Wagner’s tetralogy as a historical and semantic backdrop, there is no concern for Wagner apparent in the performance itself, as if the guests really did break into the operatic tradition, take shelter in its durational form and help themselves to its expressive techniques. Nevertheless, the captions and clips that circulated after the opera’s premier revealed the part’s unlikely achievement: it staged an encounter between Wagner—both the artist and the figure of a virulent, anti-semitic strain of German nationalism—and a class of young aesthetes who would not otherwise traffic in lines of Romantic verse or identify themselves with figures of the German national mythology.

Yet, it is possible that Wagner was and is already standing in the room. Fahima’s gesture is telescopic. By collapsing together seemingly disparate points in musical history, his opera suggests that no person who parties or perhaps even dwells on German soil can fully disinherit themselves from Wagner or the world that made him. However distant this estate may seem—especially from something as unassuming as a party—its legacies are as immediate as those of nationalism or empire. Wagner left an indelible mark on this inheritance. If this mark cannot be erased, if its archives cannot be dissolved, then the only adequate response would be to break in, paint over the walls, and practice living anew.

As a party, Fahima’s opera is not a laboured means to these ends, and it does not need to be. Both participants and viewers find the tetralogy to be hospitable and capacious enough to squat in. This openness is, however, generally true of Wagner’s work, and not just for the artists, musicians, and performers who succeeded him.

Wagner’s endowment, which he himself inherited, comprised more than a history of music. For several decades leading up to the mid-nineteenth century, dandies, feminists and anarchists alike found Wagnerism an eclectic, catch-all label for diverse political aims. The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, the darling of nineteenth-century composers, helped Wagner fashion music into a modern paradigm of identity or inwardness. Since Wagner, music provides a way for isolated individuals to overcome their private experience and recognize by way of melodic expression that subjective, inner feeling is an experience shared in common. A one-time friend of the composer, Friedrich Nietzsche also saw in Wagner’s music a power of tragic revelation, capable of disclosing this fundamental truth about human experience. However, Wagner’s descent into folkish nationalism was, for Nietzsche as for present-day observers, a reversion to a fractured and reactionary worldview of the “overwhelming feeling of unity leading back to the heart of nature” that Wagner’s opera ought to have expressed. Still, despite his attempts to overcome Wagner as a representative of diseased modernity, Nietzsche, like Fahima, still insists on appropriating or sheltering vibrant forms of life in this intellectual heritage.

As Fahima’s opera shows, a party is not just a gathering but a medium in which sound collides with musical tradition, with material bodies and the ideal worlds that they bear. This conjunction is what Fahima references in the full title of the work, On reading #foucault’s #lusagedesplaisirs feat. a very slow #bohemianrhapsodyremix [aka The Rules of Attraction, opéra concrète]. An image on Fahima’s Instagram reveals the occurrence behind this peculiar formulation: a book lies unnoticed at a noisy, Berlinois gathering of queer folk until it catches the artist’s eye and offers up its contents. Fahima’s viewer, then, joins this gathering in the halls of a troubled but irreversible heritage with an invitation to overwrite its sounds and meanings. Promising and vernacular, this occupation does not aim to dissolve the estate, but to abuse its generosity, redraw its inferences, and inhabit its joys.

CREDITS

TEXT / Alexander Lepianka @polishwatersports

Concept, Production and Live Direction / Alexander Fahima @alexanderfahima

Set Design / Matthew Bianchi @sensitivefatherfigure

Costume styling / Emmanuel Pierre @epeerie

Production Management / Leanne Mark @leannemark and Jimmi Kriste @lurid.sensation

Action Painting / Mauro Ventura @sollidha

Solo / Steph Quinci @isabellaparigi_

Video Call Performance / Darian Mark @dariangmark , Lili Dobronyi @lasenza_girl

Remix / Patrick Mason @iampatrickmason

Dinner / Generation Black @_generation_black

Casting / @mother.loading

Dramaturgy / Selin Davasse @radicalized_faghag

Live-Editing / William Reiss

Set Design Assistant / Olivia Ballard @oliviaballardballard

Video Artwork Assistant / Deividas Vytautasad @deividasvytautas

Featuring and filmed / @alyhalovemustdie @lascenseuremotionnel @federey @_iliaspaci_ @justkennyx @linakoel @sollidha @sensual_psycho @groovy_ch1ck @oliviaballardballard @algard @shse2000 @isabellaparigi_ @iampatrickmason/