Some might feel you just recently emerged on the scene, but you’ve been an active artist since 2002 and probably beyond. Do you feel like your current fame is suddenly more intense?

Yes, I’ve been doing theatre around Europe – and beyond – for over 20 years. But when I started writing songs and touring with concerts, my audience kind of multiplied by ten. Still, that doesn’t automatically make me a star or “popular” in the music industry sense. My audience is mostly artists, intellectuals, and some beautifully weird people. I’m far from being mainstream-famous, especially in music – but I don’t mind that. I like where I am.

What do you think catapulted you to stardom, specifically? What is the most relatable thing about you for your fans, in your opinion?

I think the most accessible part of me is my “gay” voice – that’s number one. Then come the melodies, and then the lyrics. Those are the top three qualities that people can connect easily. After that, maybe it’s the emotional availability, the honesty… and, not least, my humour and my irony. My tendency to make fun of myself, and also of things that matter – to me and to society. It’s all part of the same package.

The “About” on your website states that you’re a theatre maker and choreographer first. How does this part of your life intertwine with touring and appearing on the stage in a different context?

I’m definitely stretched between two very different careers – one in theatre and choreography, the other in music and songwriting. Sometimes I manage to bring them together and create bridges between those worlds. But often they exist in separate contexts – different industries, different audiences. Still, I love it when they overlap. Some people come to my concerts because they know my theatre work, and some come to my theatre shows because they like a few of my songs. Then suddenly they find themselves in a performative, complex piece they maybe never expected – and that’s a beautiful clash.

How do you feel you and your art are perceived in your native Bulgaria?

I’ve created more than 40 stage works over the past 25-30 years. Usually, my favourite is the last one – because it’s fresh and takes me into new territory. But if I look back, Som Faves is probably the one that represents me best. It was built on 100 different topics, and I loved spreading myself that wide, touching so many themes and ideas. I toured it a lot. It was also very compact – just a keyboard, a small painting, and a cat. It all fit in one suitcase. I love making shows that travel light.

My most recent solo piece, METCH, might also be my favourite. Yes, I have to travel with 40 of my paintings, but it includes so many new elements – new drama, new ways to relate to the audience – while also echoing past works like Lili Handel, I-Cure, and P Project. It opens a new conversation.

How do you feel you and your art are perceived in your native Bulgaria?

My audience in Bulgaria is incredibly supportive. The general Bulgarian public is more shy, more suspicious than Western audiences – sometimes more introverted – but I do my best to make my work accessible. At the beginning, some were shocked, like when I performed P Project and had the audience participate and even get paid during the show. For some, that was disturbing. For others, it was a joyful revolution. It’s usually very polarised – but I believe most cool people say “yes” to my work and my way of expressing ideas.

How different is it for you to sing in your mother tongue compared to English? My perception is that your voice has a lower register in Bulgarian. Do you feel some sort of internal difference when composing in either language?

When I sing in Bulgarian, my voice becomes more raw, more grounded, a bit more aggressive – sometimes even a little macho, especially with the folky songs. It’s heavier. Maybe that’s how I help people recognise the sound as part of their culture. It’s not something I plan consciously – but I do notice it. Singing in that way can be more exhausting, but I believe it helps the message land better. Because my content isn’t always easy – I can be contradictory, subversive – so I make the form more familiar, so people can access the meaning. Interestingly, when I sing in Bulgarian, I also sound less queer than in English – but that’s just the vocal colour. The content might actually be more subversive in Bulgarian, because there’so much more to subvert here in Bulgaria.

How do the themes you sing about come to you? Do you decide you want to sing about a certain topic and write a specific song to deliver a message, or is it more instinctual for you?

I only write about things that are important to me. And “important” doesn’t just mean things I love – it includes my fears, my shame, my shadows. I try to give equal respect to the light and the dark, in myself and the world. There’s no discrimination – everything deserves to be sublimate in a piece of art, to become a song, to be celebrated.

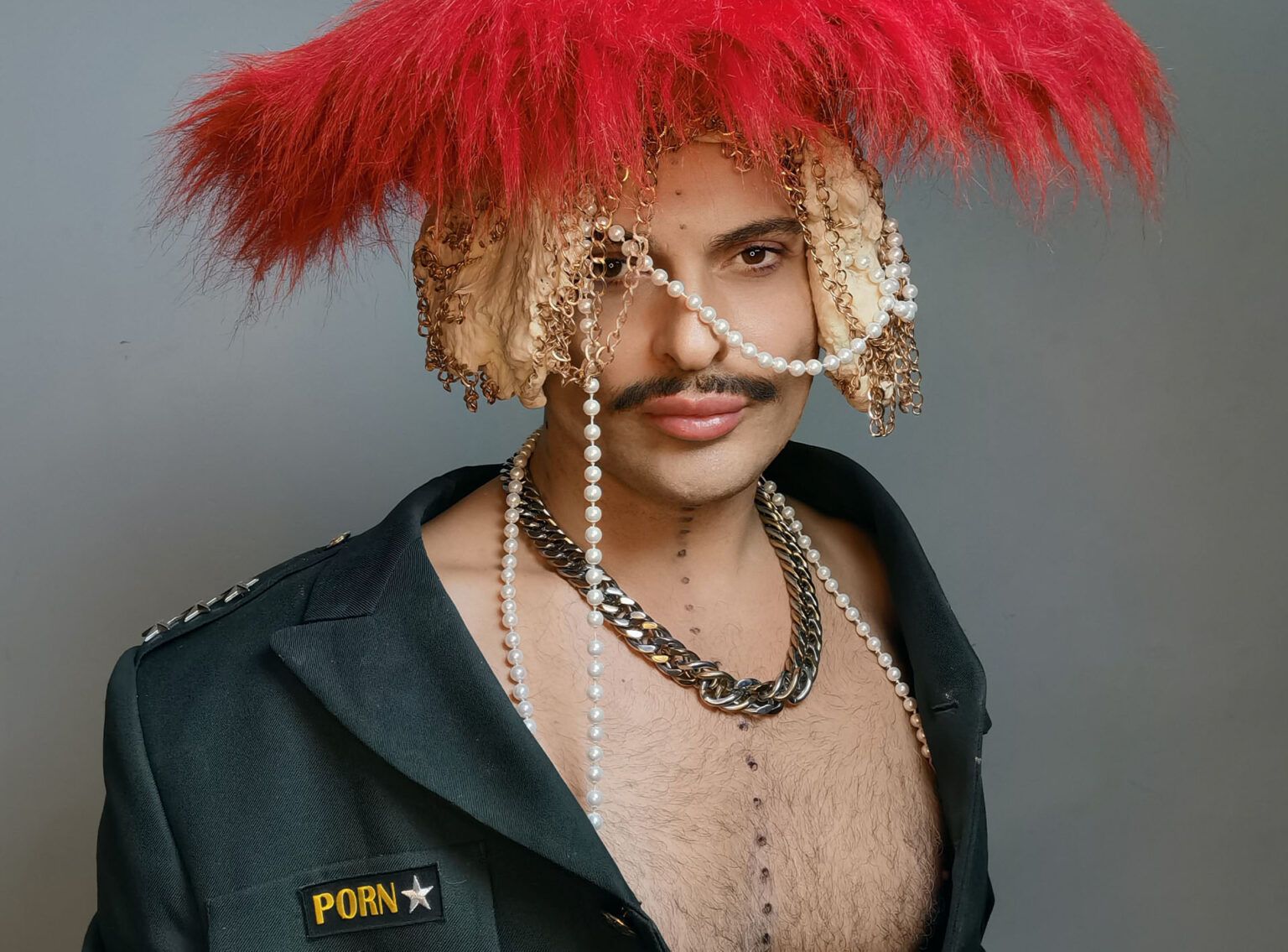

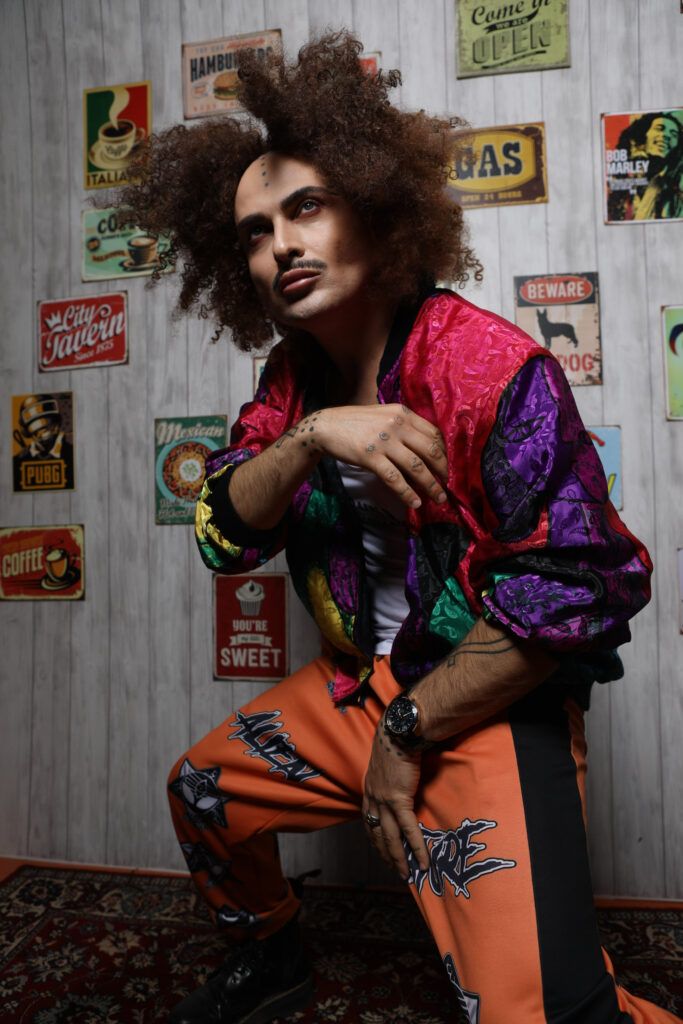

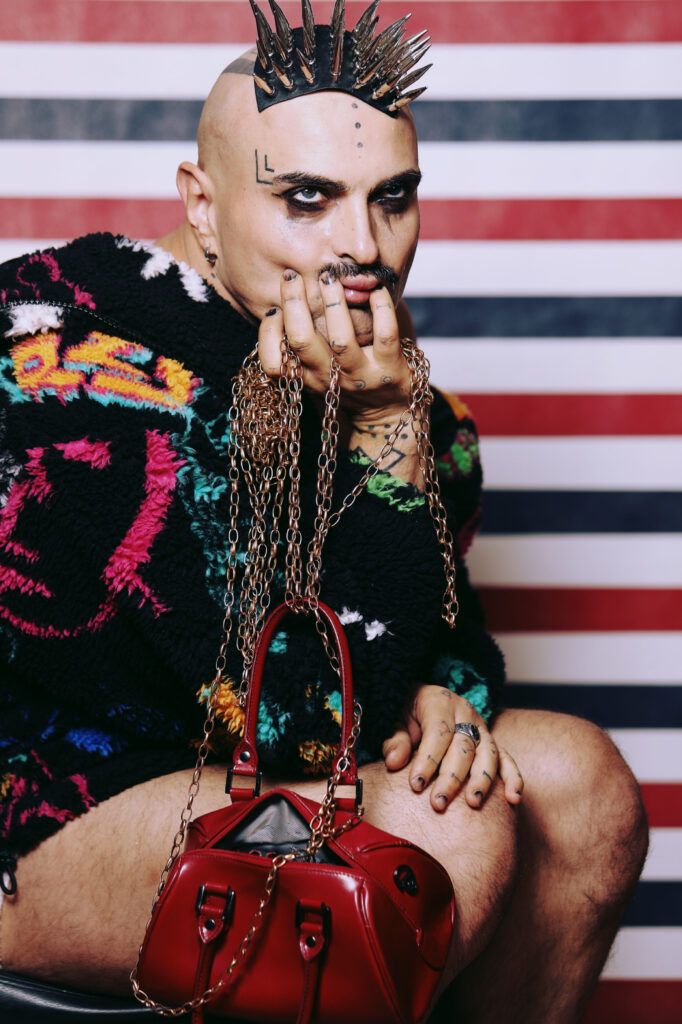

Your style and visage are always very colourful and eye-catching, and also change quite often. What inspires you regarding your self-expression?

I believe that the performative body is not a normal body – it’s not binary. It’s male, female, animal, alien, machine – all at once. It contains evolution and contradiction. So I allow myself to constantly transform. Of course, it may not be as diverse as it seems; I’m always within a queer, colorful, trashy aesthetic. Sometimes, I allow myself to be minimal and stylish, but rarely. My main drives are colour, contradiction, and queerness.

What does queerness mean to you? How do you experience the world through this lens?

I’m not a specialist in queer theory, but for me, being queer means being openly non-binary or gay, or simply non-traditional – and being proud of it. It means being ready to talk about it, to protect it, and to pay the price for being different. It’s not just a label, it’s a position.

Do you have artists whom you would consider your muses? Are there any figures, styles, and influences that directly shaped you and your expression?

When I was a little boy, I loved Kenny Rogers. Then came Elton John, his music was my safe place when I was a bullied queer kid. I even wrote a song called Elton John. Later, I fell in love with jazz: Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone. Madonna’s Girlie Show changed me, inspired me to dance, stretch, do yoga. Annie Lennox’s Diva album, I was addicted to it. Then Björk. Then, The Emancipation of Mimi – Mariah Carey! I trained my voice for years with her music. Now… I just listen to chill playlists on Spotify. I’m too busy with my own music. When I’m alone, I want silence. Or sex. Or chill vibes.

Is there a comparison to any fellow artist that you would consider the highest compliment?

I don’t like comparisons that much. No artist does. People do it to try and connect, and most of time, they have good intentions, but for us, it’s not flattering. Every artist works so hard to have their own voice, their own message. Sometimes, we might sound a bit similar, but it’s the content that matters most for me – what you stand for. That’s what makes you truly unique.

Is it your first time at the Pohoda Festival?

Yes, it’s my first time, and I’m very excited. I’m grateful to be invited and curious to meet people from the region. For me, every performance is a conversation – and every conversation is different. I’m looking forward to seeing what this one will be.

Is there a question you would love to answer, which you haven’t been asked yet?

Nobody ever asks me why my songs aren’t on the radio. And the answer is: they’re not meant to be. Each song is a sentence, a piece from a much longer conversation with my audience. Some of those sentences get more attention, others less. But none of them are written to be hits. They’re written to be honest and to give direct access to a particular part of me.