Your creative path didn’t begin in fashion – it started in the lab. What did the world of pathology offer you that fashion eventually replaced or redefined?

I started in pathology because of my analytical and curious nature. I’ve always loved experimenting. But I quickly realised that working in the lab was serious business. It wasn’t that I didn’t take the tasks seriously; in that environment, one wrong measurement could have huge consequences. Everything had to be measured precisely, orders had to be followed strictly, and the process had to stay on track. What I soon realised was that I was missing something, my own element. What was I actually offering? I was mostly learning from books and applying that knowledge, but nothing I did really screamed Sumeyya. I’m not saying that every task needs to have a personal touch, but it’s important to work with passion and purpose.

After deciding to leave, which my chemistry professor actually encouraged me to do, I felt lost and empty. I had always been creative, but back then, I didn’t believe I could find a career in a creative industry. I stopped listening to my doubts and started applying to art schools. Of course, I was rejected at first because I didn’t have a proper portfolio.

Eventually, I applied to a fashion course, explained my background and got accepted. It began with that acceptance, but I think many fashion and art students, including myself, want to feel accepted and seen. Sometimes, that leads to trying to impress others instead of focusing on your true purpose. I remember asking myself during graduation: This might be your last collection—what do you REALLY want to do? I realised that once I started creating what I genuinely enjoy, without strict rules or fear of consequences like in the lab, it began to fill that emptiness and gave me a real sense of purpose.

So, to return to your question: fashion replaced the rigidity of the lab with the freedom to create without needing approval. Two personas will always live within me: one, the professor shaped by the world of pathology, who analyses, plans and chases perfection; The other, the artist, who embraces creativity and imperfection.

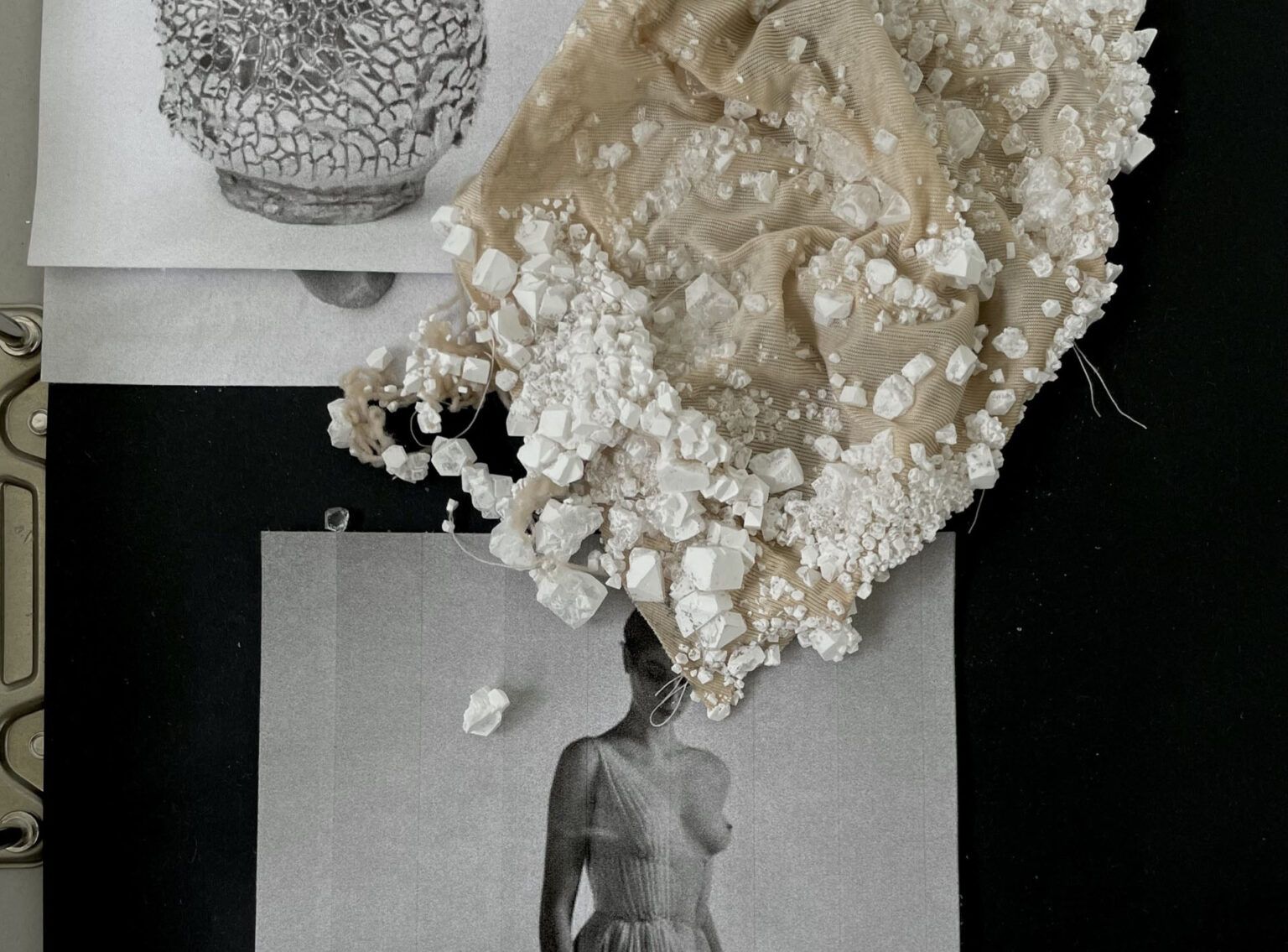

Your garments crystallise in a salt bath over several weeks, there is something spiritual in that slowness. What have these waiting periods taught you about time?

I love this perspective! When I first started crystallising, I realised how calming and meditative the entire process was for me. It felt like ascending to a different state of mind, allowing me to live in the moment. That’s one of the greatest lessons the process has taught me.

We live in a world where fast fashion and instant gratification in general are normalised. Everything happens so quickly and easily now: we don’t have to dive deeply into books, wait for meaningful conversations or slow down in any way. The slow process of crystallisation stands in direct contrast to this rapid pace. It requires patience, presence and trust in time. Waiting for the crystals to grow makes the final result even more valuable and special. The beauty unfolds slowly, which reminds us that some things are worth the time and care they demand. So the process itself becomes a spiritual practice, an embrace of slowness in a fast-moving world.

Salt is a symbolic material – healing, protective, preserving, and even destructive in excess. What drew you to it, and how do you understand its role in your work?

During my graduation, I experimented with a variety of materials, always through a scientific lens; things like biodegradable plastics, fruit leather, and other alternative textiles. I first came across crystallisation during a textile course in my first year. I didn’t pursue it deeply at the time, but I took a photo of the experiment and told myself, ‘One day, I want to come back to this.’ Graduation felt like the right moment to finally revisit that idea and see where it could lead.

What initially drew me to salt was its slow, almost meditative process, the way crystals form gradually, one by one. There’s something fascinating about witnessing that kind of natural growth. It teaches patience and presence. Crystallisation doesn’t allow you to rush. It invites you to slow down with it, to surrender to time. But it’s also unpredictable.

You can never fully control how or where the crystals will grow. Sometimes, they surprise you, forming in unexpected places or changing texture overnight. That unpredictability is part of what keeps the process exciting. It reminds me to let go and allow the material to take the lead. Salt is also deeply paradoxical. It can look solid, sharp and durable, yet just a little warm water is enough to dissolve it completely. That fragility alongside its strength really resonates with me. It reflects life in many ways: how things we believe to be stable can suddenly shift or vanish.

I knew I wasn’t the first to crystallise garments or objects with salt, there are a few artists and designers who have explored it before me. But I was determined to find my own signature within that process. I began blending different types of salt together to create new textures and formations. During graduation, I didn’t have the time to fully refine the technique, but I knew I had found something meaningful. After graduating, I continued developing it simply because I loved the process. Now, three years later, I’m still learning. Crystallisation keeps surprising me. Each experiment feels like a new discovery and, because of the nature of the process, every piece is one-of-a-kind. I couldn’t duplicate them even if I tried.

There’s a sense of sacredness in your pieces as if they belong in a shrine rather than a closet. Do you see them as objects to be worn or as art objects?

My work sits somewhere between clothing and sculpture. It often starts as a garment, but once it goes through the crystallisation process, it changes, becoming more fragile and temporary. Technically, you could wear it, but that’s not really the point. The fact that it can’t be worn easily makes it even more interesting. There’s a tension in that: it looks like fashion, but it behaves like art. They feel more like frozen moments, delicate and meaningful, as if they hold a quiet kind of importance. I don’t really see them as garments anymore. To me, they’ve become art objects. My process is deeply experimental, I call every single item I create an experiment. Each piece is truly one of a kind, shaped by the unique growth patterns of the crystals, which cannot be duplicated or reproduced. I also believe that fashion doesn’t have to be wearable all the time. Sometimes, its power lies in provoking thought, emotion and challenging our ideas about what clothing can be.

Looking back at the path that led you here, from the lab to the fashion studio, what would your younger self say if she could see your work now?

I think she’d be quietly amazed and maybe a little confused. I didn’t take a traditional path, and back then, I couldn’t have imagined combining scientific experimentation with something so emotional and tactile. But I think she’d recognise the curiosity. The same desire to observe, to test, to understand materials deeply, that’s still at the core of what I do.

She probably also didn’t expect the path to be so experimental, shaped by intuition rather than a fixed plan. And I’m sure she never imagined there would be people out there who admire this work. That part still feels surreal, and I’m incredibly grateful for it. But most of all, I think she’d be proud that I followed that curiosity all the way through, that I gave things the time to unfold slowly instead of giving up.