Your work delves into the phenomenon of post-truth and the mechanisms behind it. What initially drew you to this subject, and how do you translate these abstract concepts into visual art?

Post-truth caught my interest as a mechanism for creating alternative versions of reality – often more compelling and persuasive than facts themselves. At first, it stemmed from frustration with populist politics and media manipulation. Over time, rather than trying to oppose these forces, I decided to consciously make use of the same tools – emotive messaging, or the aura of revealed truth – to draw attention to how beliefs are formed, especially that kind we tend to accept uncritically.

That became the starting point for my doctoral work. It led to a series of paintings exploring how virtually any assumption can be elevated to the status of “truth” if presented the right way. One of the works referenced a thought experiment by Bertrand Russell–it concerned belief in an absurd object: a cosmic teapot orbiting the Sun, whose existence can neither be proven nor disproven. Around the same time, I was also developing works inspired by Austin Osman Spare’s concept of sigils. I began painting strange, occult-like symbols that, in reality, carried no meaning at all.

As time went on, post-truth became more of a method than a subject in my practice. In 2019, together with my friends – Paweł Baśnik, Jędrzej Sierpiński, and Nikita Krzyżanowska – I founded the Nihilist Church: an art collective and nomadic gallery operating on the edge of Dadaist irony. Our aim was to create a space that doesn’t proclaim revealed truths, but also resists sliding into cynicism. It’s a pessimistic form of engagement that uses absurdity and grotesque to comment on the world around us. We work performatively, anti-hierarchically, and subversively, dealing with the crises of religion, politics, and the environment.

At the same time, I co-founded another project: Bezimienny (Nameless Hero); a painting collective I’ve been developing since 2019 with Paweł Baśnik and Jędrzej Sierpiński. The project is rooted in Gothic, a cult video game series in Poland. For the first year, we operated anonymously, creating a credible illusion in which the paintings were made by an avatar from the game. Through that, we were testing the mechanisms of post-truth, identity performance, and the idea of the artist as a brand.

You employ a pseudoscientific aesthetic to highlight the absurdity of conspiracy theories and fundamentalist beliefs. What role do irony and humor play in your work?

Irony, in this context, serves a demystifying function. It’s not about ridicule, but rather about creating a sense of distance from structures that try to impose a ready-made image of the world. My works often hover on the boundary between the sacred and the mystification. I construct forms that resemble worship artifacts, yet offer no clear interpretation. In this sense, irony is not just a critical strategy, but also a way to reclaim spiritual space.

Your artworks are described as an iconography of an imagined religious system. Could you elaborate on how you construct your own symbols and abstract ornaments?

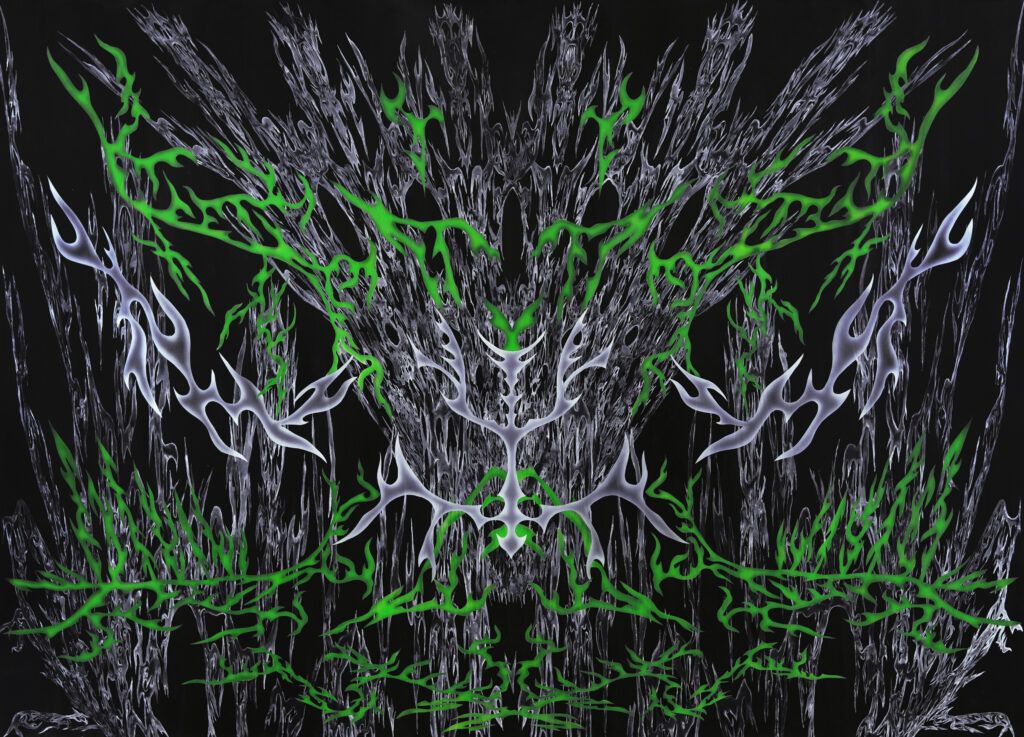

They are expansive, almost fractal-like structures in which symmetry plays a key role. It’s one of my fundamental formal tools. I use it consistently, as it lends the works a sense of grandeur and helps to build a particular atmosphere. The design process usually takes the longest. I begin with a general sketch, which I gradually densify; the ornamentation often grows outward from the center. A lot depends on the specific painting or sculpture. Sometimes I only have a vague vision of the mood I want the piece to convey, and the whole thing unfolds quite intuitively during the design phase.

When designing ornaments, I often draw on specific art historical periods, especially Gothic art. I have great respect for historic art. It’s an important source of inspiration for me. That’s why I usually begin work on larger projects with visits to museums.At the same time, despite clear references to pre-modern aesthetics, my works are firmly rooted in the present. I’m interested in playing with the tension between tradition and contemporaneity. I reinterpret historical forms through my own lens, blending them with elements characteristic of today’s post-digital aesthetics.

Your approach to spirituality is reminiscent of Malevich and Kandinsky, but without positioning art as an opposition to belief systems. How does your vision of “atheistic spirituality” manifest in your artistic practice?

For me, atheist spirituality is primarily connected to deep contemplation – one grounded in rational inner experience. After leaving the Church, I didn’t feel the need to turn to esotericism or other alternative belief systems. Art – both its creation and reception – became, or perhaps had always been, a natural equivalent to those kinds of needs.

In my work, I feel close to the ideas of Kandinsky, who believed that form, rhythm, and color can influence our inner world and help structure our experience. Even though our visual languages are different, the way of thinking about art as a tool for deeply experiencing reality feels very much aligned. An important extension of this practice is the activity of the Nihilist Church. The exhibitions we organize create our own kind of community and “mysticism.”

The ‘Adoratio’ exhibition explores non-religious spirituality through abstract iconography. What led you to this exploration, and how do you envision the audience engaging with it?

“Adoratio” was my first major solo exhibition, and I wanted to dedicate it entirely to the idea of atheist spirituality – not as a negation of religion, but as an alternative form of spiritual experience. Together with the exhibition’s curator, Gabi Skrzypczak, we wanted to approach the subject seriously, without falling back on irony.

My main points of departure were Kandinsky’s writings on Concerning the Spiritual in Art, the philosophy of André Comte-Sponville, and Sam Harris’s book Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality Without Religion.

The exhibition space was divided into three sections. Each had its own distinct character, but together they formed a cohesive narrative. At the center was a series of green-toned paintings, including the two-and-a-half-meter-tall titular piece Adoratio, which served as an introduction to the entire exhibition.

Further on, I placed an object inspired by the classical form of a solar monstrance – but without the host. In its place appeared only black ornamental forms. In the same room was a small bronze sculpture and several paintings framed in handmade frames I created myself, featuring sharp, aggressive shapes inspired by primal belief systems.

The most important part, however, was the underground crypt, immersed in near-total darkness. It took time for the eye to adjust, gradually revealing hidden details. At the center stood a wooden, abstract altar. The atmosphere was completed by the scent of natural incense, burning in old censers I had found at a flea market, and ambient music composed by my friend Michał Gątarek. I wanted the audience not just to view the exhibition, but to enter into a deeper relationship with it – to step inside as if into a contemporary, secular temple.

Can you describe the process behind creating the objects in ‘Adoratio’? What materials and techniques did you use?

Most of the paintings were created using airbrush techniques, with stencils I prepared by hand. This allowed me to achieve perfectly smooth lines and subtle tonal transitions, giving the works a different character than those painted with a brush (as in the case of Vanitas). It’s a time-consuming technique, but one that offers a high degree of control over form.

When it came to the sculptural objects, such as the Monstrance and the Altar, I worked with multiple materials and techniques in parallel. Both were primarily made of wood, with elements that were laser-cut, CNC-milled, assembled by hand, and finished using various woodworking tools. The Monstrance also featured hand-turned details, while the Altar was the most technically complex piece in the entire exhibition. I wanted it to fill the space – it was designed specifically with the architecture of the Łęctwo gallery in mind.

The small bronze sculpture placed on the upper level of the exhibition was one of the most time-intensive works. After designing it, I sculpted it by hand in plaster before it was cast in bronze.

The Temple of Tales – Mythology, Nature, and Time Your installation at BWA Wrocław builds an alternative religious history inspired by Apollonius of Tyana. What drew you to his philosophy, and how does it inform the visual language of the space?

One of the exhibition spaces I co-designed with my partner Paweł Baśnik at the invitation of curator Joanna Kobyłt, was a speculative response to the question: what if “Apollonism” had become the dominant religion? Apollonius of Tyana was a figure believed to possess healing powers and prophetic insight, but it was his philosophy – focused on metempsychosis, reverence for life, vegetarianism, and contemplation of nature – that drew our attention the most.

In designing the space, we wanted to envision a form of spirituality that was not anthropocentric, but grounded in relationship with the natural world. In my painting series, I focused on solastalgia – a term describing the existential anxiety caused by the loss of the natural environment. The installation also included an object: a tabernacle containing an ammonite fossil, reliefs of trilobites, and several other artifacts.

An integral part of this narrative were also Paweł’s works: a portrait of Apollonius of Tyana and a series depicting animal hybrids, serving as visual metaphors for interspecies kinship. Together, we also designed a large-format jacquard tapestry portraying Orpheus playing music to wild animals – a symbol of harmonious coexistence and interspecies affinity.

The use of ammonites, trilobites and references to geological time gives your work a sense of deep history. What is the significance of fossils in your artistic storytelling?

For me, they are material evidence of a world that existed before humans on a scale that surpasses our everyday understanding of time. They are a reminder of the persistence of life – life that didn’t begin with us and doesn’t necessarily have to end with us.

In the exhibition, fossils appeared in several places and each of them held meaning. At the center of the space, I placed the aforementioned “tabernacle,” inside which, in the role of a relic, rested a genuine ammonite fossil that I purchased and treated as the focal point of this speculative temple. The spiral form of the shell also references the golden ratio, often seen as a symbol of cosmic harmony.

The trilobite reliefs and other plant and animal fossils were kindly loaned by the Geological Museum in Wrocław. These are authentic, untouched fragments of the past–not artistic interpretations. Their presence lent the entire space not only physical but also symbolic credibility. Fossils remind me that we are only a brief chapter in the vast history of life on Earth.

You explore solastalgia, the grief over environmental change, in your paintings. Do you see your work as a form of ecological activism?

In these works, I commemorate trees that are characteristic of our climate zone: birches, larches, pines, and spruces. The awareness that many of these species may disappear from our region within the next few decades genuinely saddens me. It was both an emotional and conceptual experience – I’ve been vegan for years, and ecological issues are deeply important to me. I believe that art, in this case, can also serve as a form of activism – a way of restoring sensitivity in a world where we are systematically taught to suppress it.

What questions or emotions do you hope your audience leaves with after experiencing your work?

I want my work to be one of the possible paths for people who have left religion and feel a certain kind of emptiness because of it. I’ve noticed that many turn toward irrational beliefs – often simply because there’s a lack of space for a form of spirituality that isn’t rooted in faith. What I’d like to show is that the contemplation of art can fill that space in a way that is both profound and grounded in a scientific paradigm.

I also hope that people who identify with traditional religions can find something meaningful in what I do – perhaps through shared visual codes, or the specific atmosphere I try to create.

What’s next for you? Are there any future projects or themes you are currently exploring?

I’m currently working on a new painting that will be presented in the group exhibition Æon, held at the London location of Krupa Gallery. The central theme revolves around viewing the world on a geological timescale–one in which human history appears as an almost insignificant detail.