Your works emerge from melting, grinding, casting – almost like forensic rituals. What do these manipulations of synthetic materials allow you to say or feel that more traditional methods cannot?

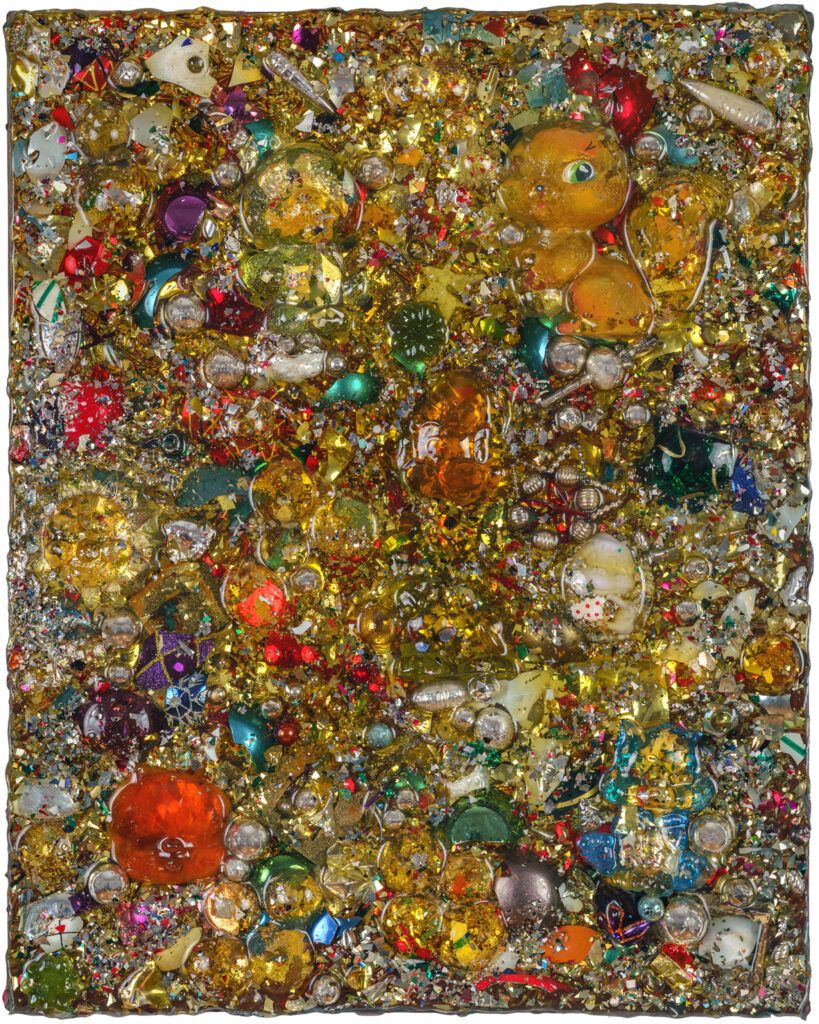

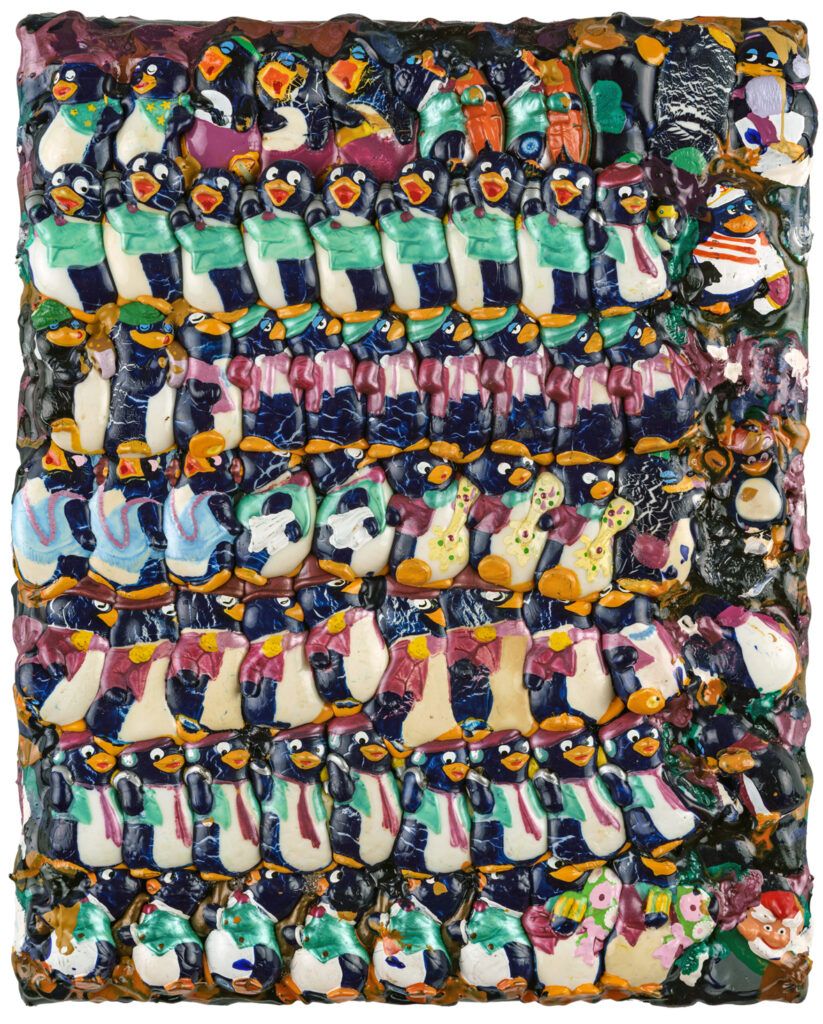

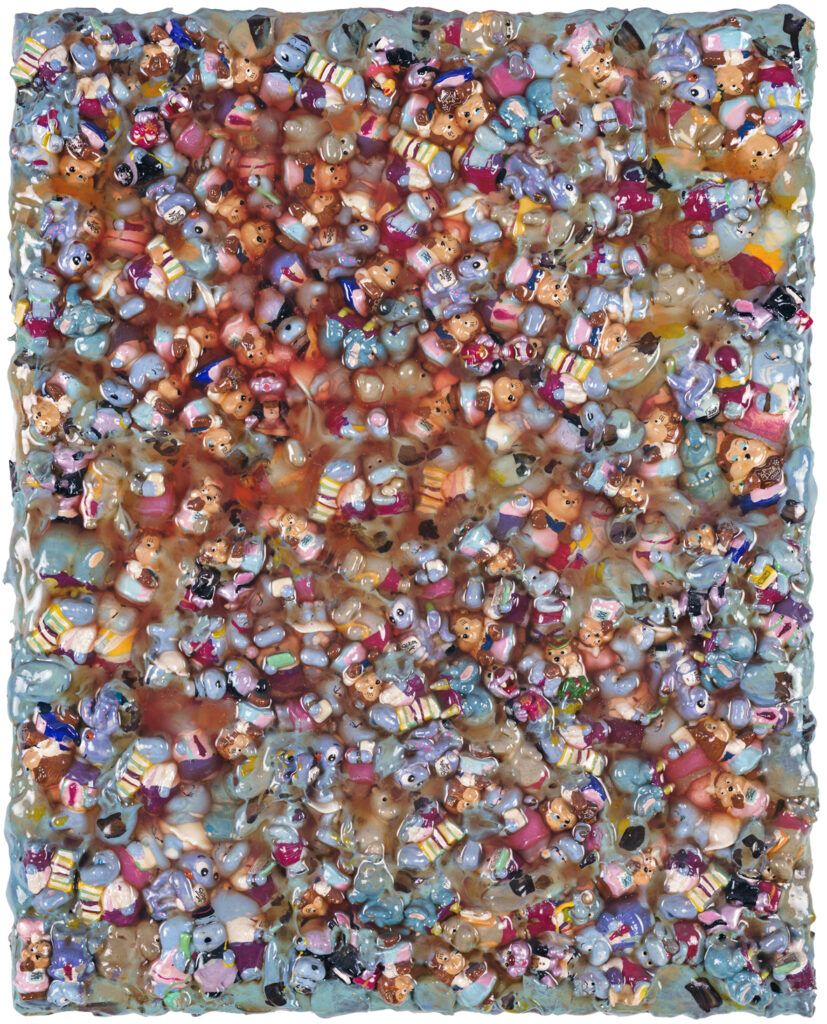

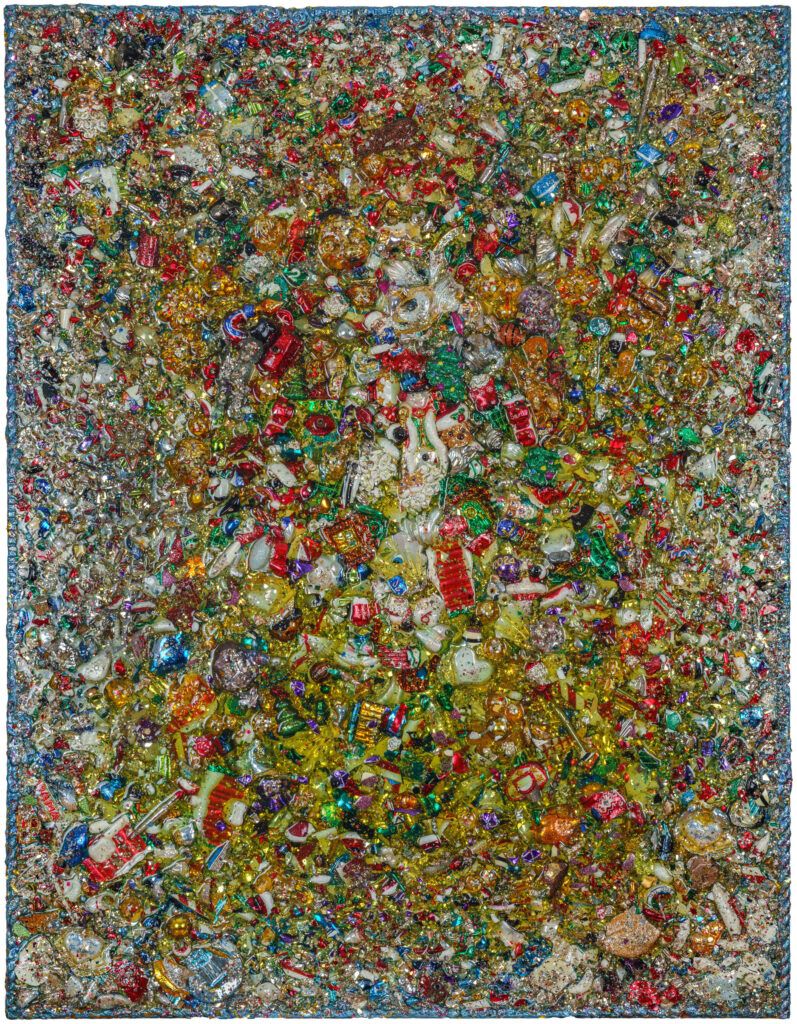

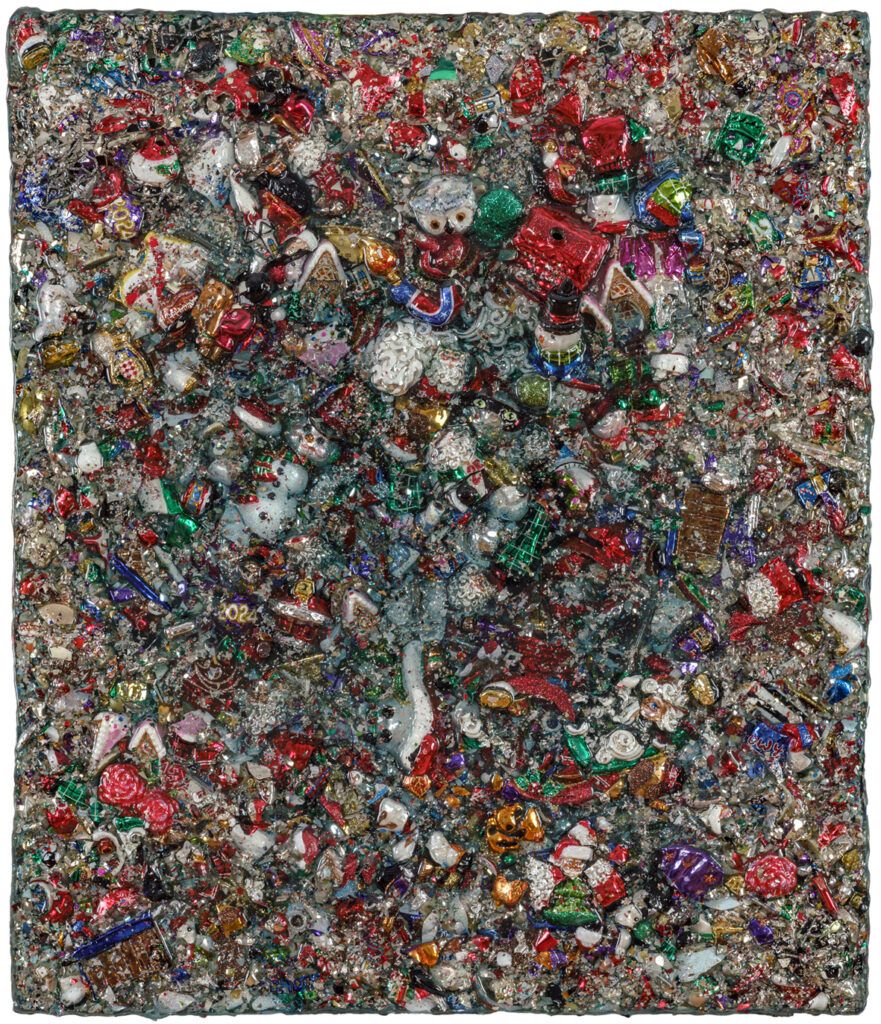

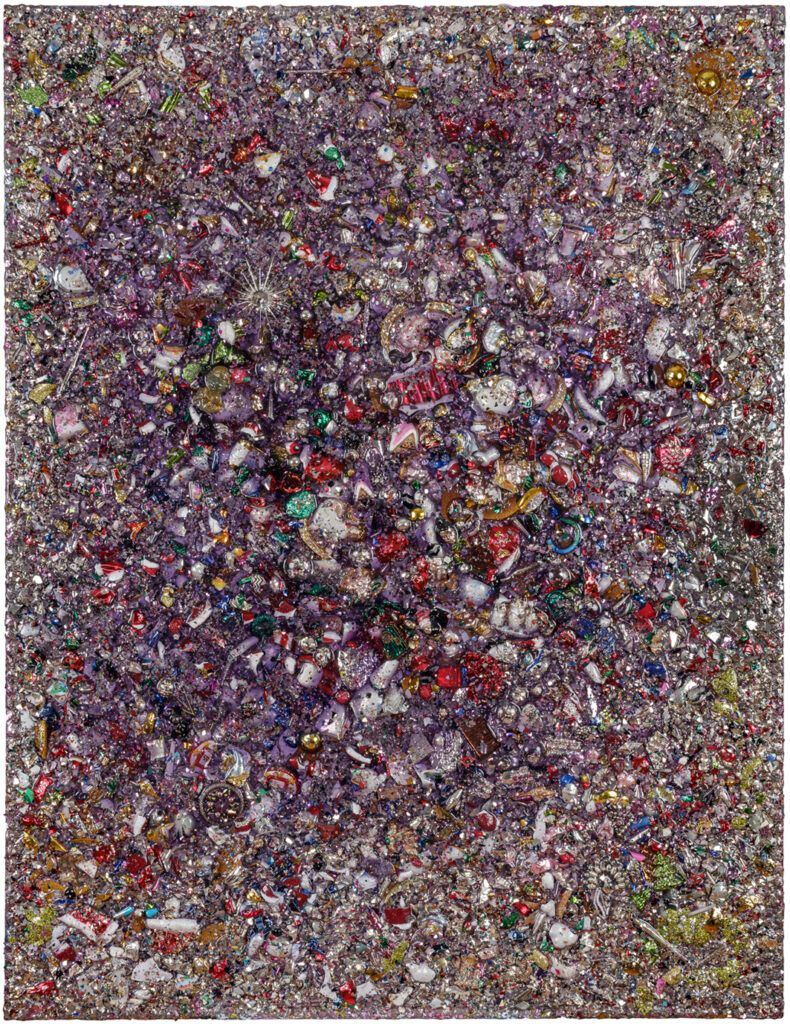

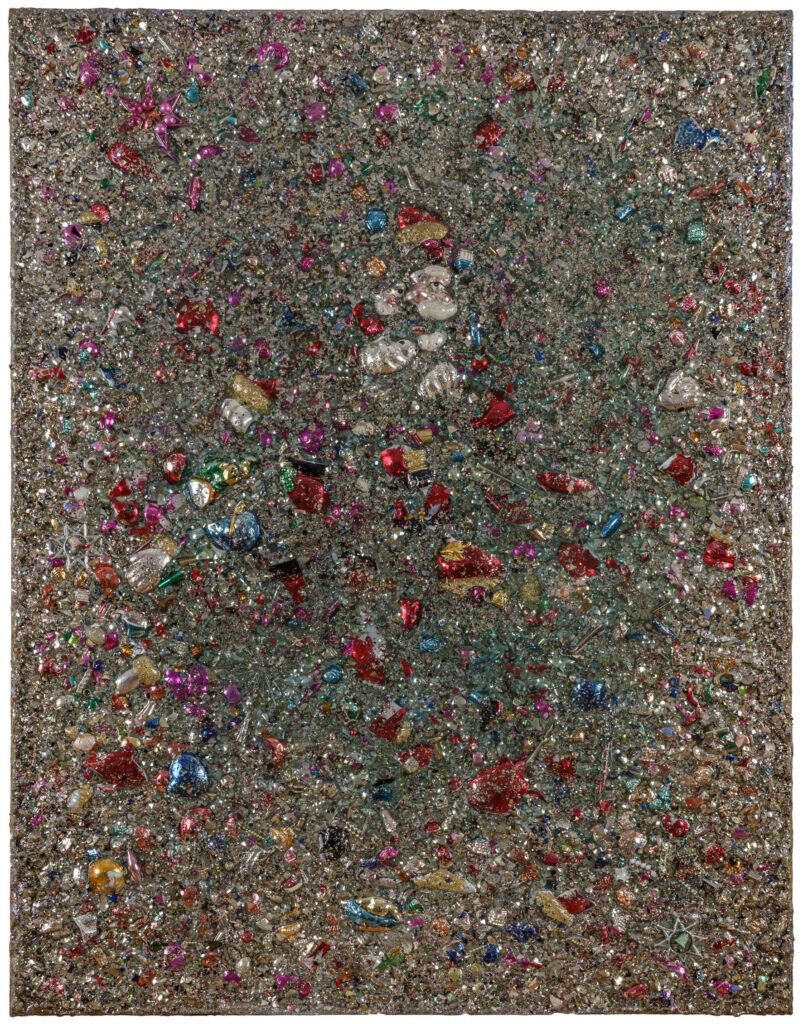

I like working with physical objects such as plastic or rubber figurines, beads, glass Christmas baubles, anatomical models, stuffed animals, and so on, because I’m drawn to their three-dimensionality, shape, texture, color, as well as the way they reflect the passage of time. I often reach for materials from the past – damaged, dented, incomplete, faded, or otherwise degrading. I use them much like paints in traditional artistic methods. I try to paint with objects, in this way incorporating them into the space of the painting. For me, the object becomes something more than just inspiration for a painting. It becomes the painting itself.

Ready-mades, toys, plastic debris – your pieces feel like they’ve survived a strange catastrophe and returned as witnesses. Do you see these objects as relics of our overproduction, or do they take on new mythologies once in your hands?

I think it’s both. Most of the objects that appear in my works come from the early days of capitalism in 1990s Poland. It was a unique time – no one was really thinking about the consequences of mass production or how it would affect us and the environment. After years of communism and poverty, the sudden flood of colorful Western goods in the shops felt like a promise of a better reality.

I have the sense that foreign-made trinkets held a kind of magic for us. They were like amulets or talismans, protecting us from the grayness and sorrow of the communist past. Owning them made us feel connected to the free Western world – a world we didn’t fully understand yet, but one that carried the promise of a brighter future. By working with objects from that era, I feel I’m engaging not only with their form, but also with the hopes and personal histories contained in them.

You navigate between figuration and abstraction, sculpture and painting, matter and metaphor. Is this crossing of boundaries a conceptual decision, or does the work demand to shift shape?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve found it difficult to define what I do in binary terms. I feel that these divisions are imposed on us artificially. As humans, we tend to categorize everything and fit things neatly into boxes – it gives us a sense of security. But in my creative work, instead of clinging to rigid classifications, I try to search, to explore, to experiment. I engage in a dialogue with these divisions to show that they don’t have to be oppositional – that they can, in fact, be two parts of a greater whole.

Childhood is a recurring undercurrent in your work, but often refracted through warped or ghostly forms. What kind of memories do you think materials hold, especially artificial ones?

There is certainly a “memory of the era” embedded in toys – the prevailing trends, promoted attitudes, all perfectly suited to be reproduced as plastic dolls or rubber figurines. Layered onto this is the personal memory of the owners, for whom a toy bought and brought home is no longer just a mass-produced object and gains a private character. It becomes a “container” for individual projections.

The 1990s in Poland were a time of hope and chaos. Society still lacked a map to navigate the new reality. Wild capitalism caused social stratification. On top of that, the adults of that era mostly came from the post-war generation. They carried with them a heavy burden of anxiety inherited from their parents, which resonated in social relationships. Growing up at that time, I absorbed that strange atmosphere of transition and unrest, and perhaps it sometimes comes through in my works.

There’s something both seductive and repellent in your surfaces – shiny, colorful, glossy, but also sticky, burned, wounded. Are you consciously playing with attraction and repulsion?

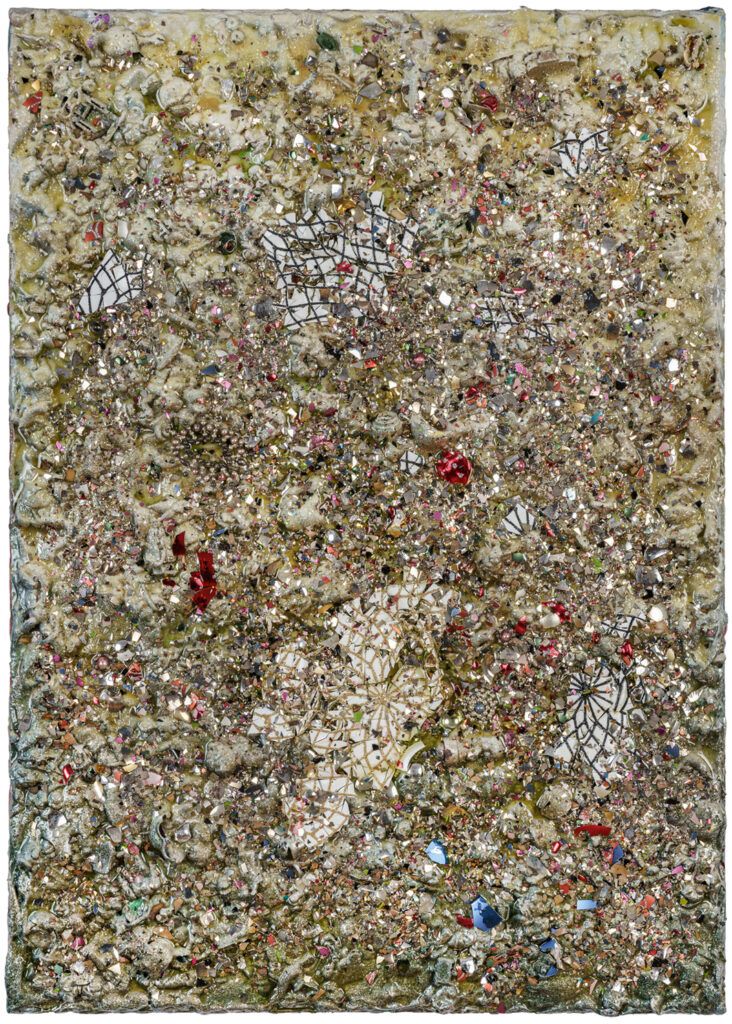

I’m interested in creating a kind of tension that evokes conflicting emotions. That’s the case, for example, with the series Sharp Glitter, in which I used hundreds of shattered Christmas baubles and resin casts. The works sparkle, seduce, draw you in – they invite touch, provoke curiosity about what they’re made of. But the surface, made of broken glass baubles, is sharp and dangerous. Touching it can hurt you.

The title refers to a practice from the early years of Poland’s political and economic transformation. Back then, glitter wasn’t as readily available as it is today, so people would crush Christmas baubles to decorate things like greeting cards.

Pop culture and consumer symbolism run through your practice like a coded language. Do you see your work as critique, celebration, archaeology, or all of these at once?

I think it’s everything at once. The culture we live in is too complex to focus on just one of its aspects. I also feel I wouldn’t be entirely honest with myself if I focused solely on criticism. I relate more to the attitude of a researcher or archaeologist, who uncovers the remnants of a lost civilization from the sand and tries to piece together how it once functioned.

You’ve exhibited widely from Berlin to Nairobi, Amsterdam to Katowice. Have different places changed how your work is received or interpreted?

I think so, yes! My works take on completely different contexts depending on the geographical region. In highly developed Western countries, themes related to overproduction come to the forefront; in post-communist countries, the theme of political and social transformation plays a major role; and in developing countries, it’s probably the issue of wastefulness that stands out most.

Finally, what’s currently fermenting in the studio? Are you dreaming of new textures, collaborations, or conceptual thresholds?

I’m currently developing my latest series, Secrets. I dream of a perfect, homogeneous structure that merges relief with oil painting.