You describe war as a “deadly game” set against the backdrop of nature—both a silent witness and a medium between life and death. What role does the landscape play in your compositions beyond setting the scene?

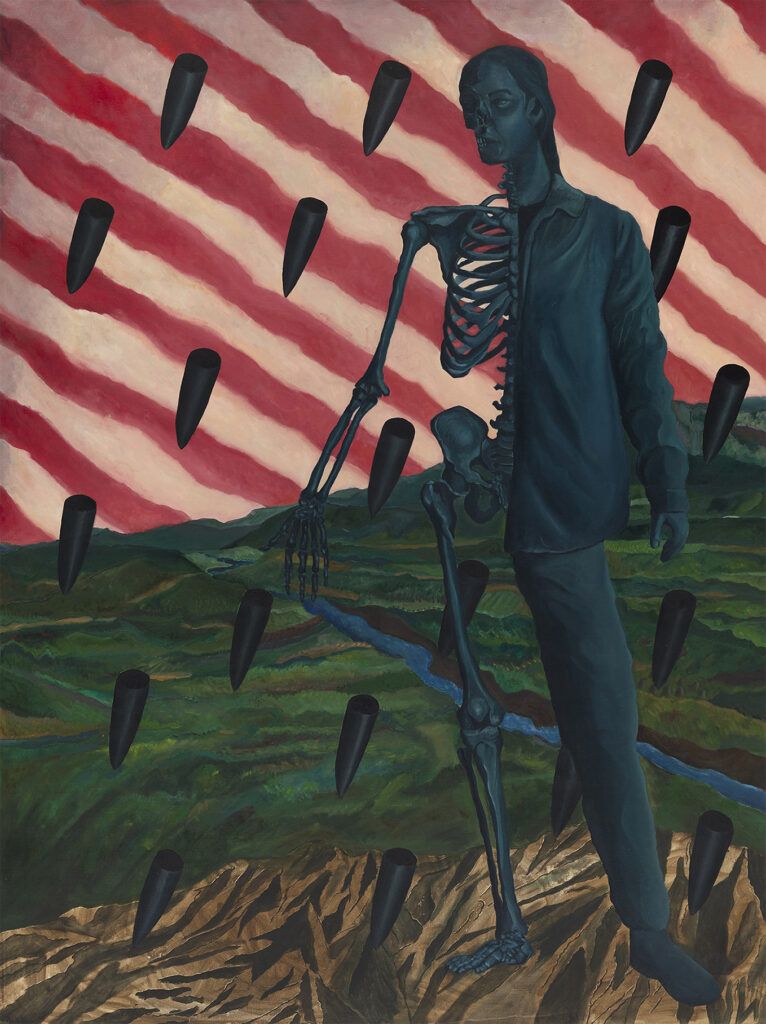

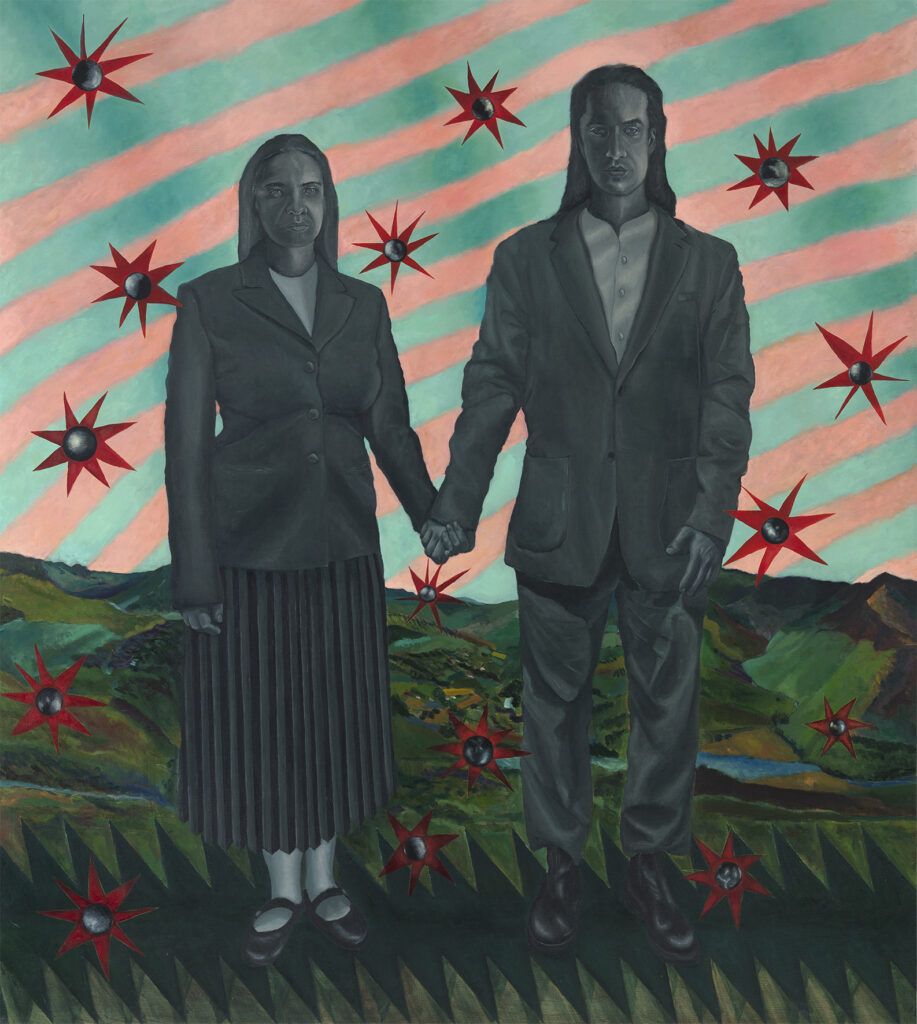

My practice is a constant battle of many opposing aesthetics and it is not a homogeneous imaging. Therefore, I do not have a clear answer, I do not have one designated method of working, a recipe for imagery. That is why the landscape in different paintings has different goals. When I started thinking about war representations 3 years ago it was a kind of impulse. I did not impose tasks on myself, I did not define goals. I acted ad hoc, implementing experiences from earlier paintings that played out in the face of nature, sometimes in opposition to it, so at first, situating the ‘place of action’ in the midst of the landscape was a natural, proven – also aesthetically – solution. Intuitively, I identified nature as the thing over which the game was indirectly played. Without being a cloying landscape, it appeared as the ideal counterbalance to the horror, the evil of the foreground. On the other hand, I never tried to aim for exaggerated realism, rather only to synthesize the whole situation, to suggest, to refer back to the memories and emotions of the viewer. Over time, the backgrounds took on different forms and thus different meanings. From those suggested only by the line of the horizon, to those looking like a field prepared for sowing grain in spring, to those already being a shapeless mass, trampled, squashed, crushed by the caterpillars of a passing tank, digested and spat out. Today, with the benefit of hindsight, when I have forcibly started to rationalize everything, I have found many of the initial decisions interesting as fertile meaning material, and the clash areas as sacred, mythical and mystical places.

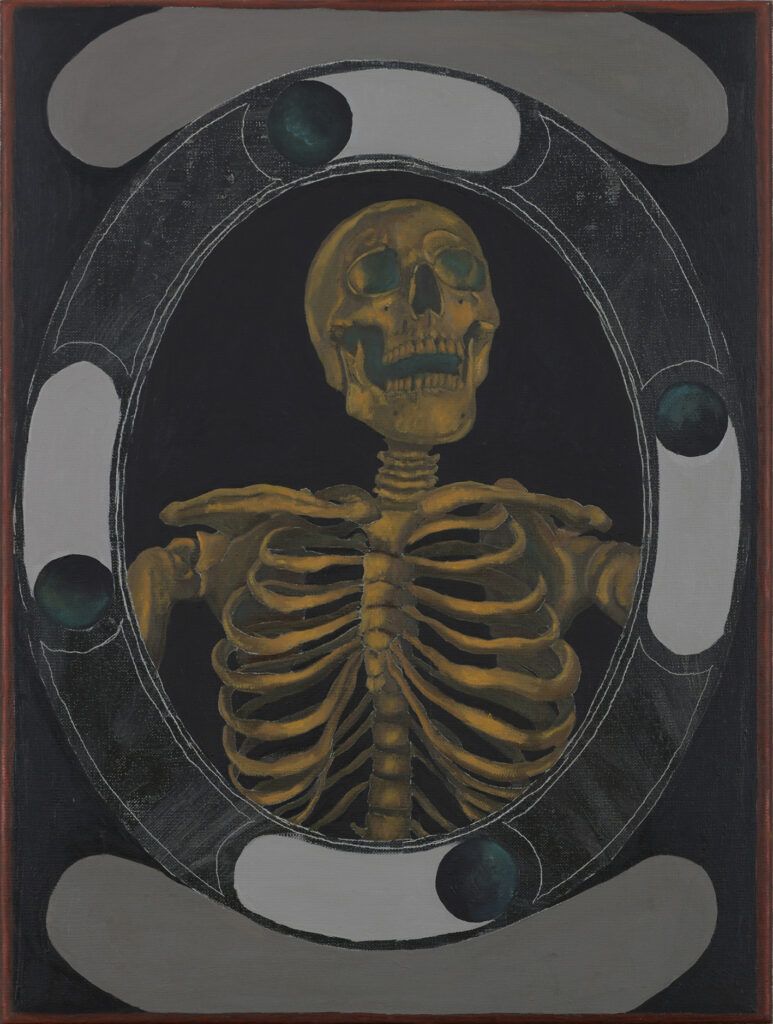

Your work fuses Baroque visuality with 20th-century avant-garde logic. What happens, in your eyes, when these temporal and ideological layers collapse into one image?

It seems to me that the current time and its visuality is very eclectic. There’s no specific, dominant trend that artists follow, so I think I’m a child of my time in that respect. The whole history of art is at your fingertips, you can reach out and use whatever you happen to feel like. You can mix up competing or canceling aesthetics. It seems to me to be wildly interesting and offers endless possibilities. I think that, despite appearances, the avant-garde and the baroque are not that far apart. Both arose as forms needed to describe a changing, crumbling world. By analogy with the current situation, when every day reaffirms that we are living in a declining moment, I balance between different aesthetics, distilling elements that are still relevant today. Avant-garde artists sought to break with the conventions that had dominated previous centuries. I link the twilight of battle painting to the development of the avant-garde, which revolutionized art at the beginning of the previous century, moving away from traditional forms and themes. I somewhat perversely draw on their imagery, resurrecting the forms to whose disappearance it contributed.

The question “Is war an abstraction?” threads through your current project. How do you personally answer that question, or are you leaving it open deliberately?

This question is a play on words, a reference to the art form proposed by the avant-garde and a polemic against the paradigm of the end of history, which has been in force until recently. It seems that the current dynamics of change in the world is only a prelude, and that the experience of war from the point of view of a European is no longer an abstraction, something unreal and distant. I think that many people are surprised to find that more and more solutions are being imposed from a position of strength, even at the rhetorical level. I fear that the answer is increasingly less optimistic.

The concept of a large-scale painting panorama—once a popular format and now largely abandoned—is central to your practice. What excites you about reviving this form for a contemporary audience?

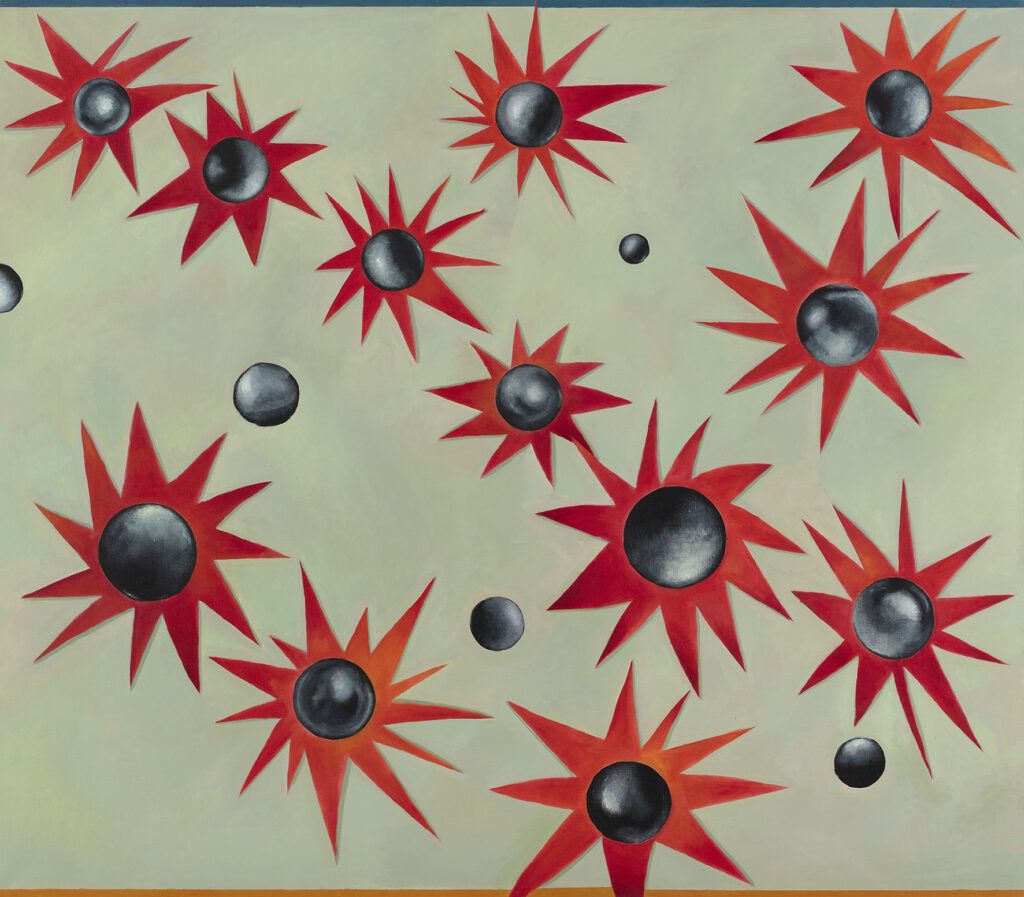

My impression is that there is currently a renaissance in painting of many classical, academic subjects, from still life to landscape and genre scenes. And such a large and rich iconography as battle painting has – despite the geopolitical situation and the threat we all find ourselves in – no resonance. In my project, I want to restore this unique format by implementing updated visual means. In contrast to historical panoramas, which are homogeneous, chronological, illustrations of events, my thinking on this phenomenon is closer to Werner Tubke and his ‘Panorama of the Battle of Bad Frankenhausen’, in which he combines realism with symbolism and allegory, and in which his work is not just a historical reconstruction, but a reflection on human nature, war, revolution and history. I am working on a series of works that, when juxtaposed, will form a single sequence. They will be juxtaposed with alternating figurative and abstract images. On the other hand, they will be conceived in such a way that they can be arranged in almost any way. Like LEGO bricks, with each combination telling a different story and creating a different context. I believe that painting, with its capacity for symbolization or abstraction, can better capture the essence of war and its impact on human beings, offering a space to go deep and not just shock therapy as is the case with ‘new’ media.

Your imagery draws from eclectic sources—Baroque engravings, ancient mosaics, even caricature and comics. What governs your visual sampling process? Is it instinctual, political, symbolic?

In a sense, each of these terms is adequate. The distillate is intuition, predilections and predispositions, then environmental and cultural conditions come in, and finally the place and time in which I move, which means politics and social thought. Theories such as ‘technofeudalism’ and the ‘New Middle Ages’ point to the immutability of human nature, to a certain cyclical nature and a return to old patterns. It is natural, therefore, to be inspired by the art of those times, subject to evolution and updating. I often wonder whether I am not merely compiling fragments that have been included elsewhere, and whether I am not thereby becoming like AI, because my practice is a montage of random, often unconnected experiences. In my mind, the provincial baroque mixes with the Łódź avant-garde. Propaganda posters from the Russo-Japanese War with ancient mosaics bitten by the teeth of time. I see hundreds of twisted maps and cacophonous battle scenes from Merian or Callot. And on them, piled up clouds of cannon smoke, rows of evenly aligned cannons, the precise rhythm of lances, whole troops lined up like pawns on a board. Numbers, bullets, explosions. The abstract shapes acting as decorative cartouches are like an interface from classic RTS. Close-ups and even caricatured close-ups like in ‘Torpedo…. Fate!’ Lichtenstein contrast with the perspective of the panoramic view. High art clashes with ludic art. I think that spanning the area of inspiration combines elements of different cultures and historical periods, it is necessary to reflect the realities of the modern world, of contemporary conflicts, where the boundaries between enemies and allies are often blurred and war has many dimensions, from the physical to the psychological and cultural. This perspective makes it possible to create a narrative that goes beyond a simple description of historical events.

Your work reconstructs the ornate visual vocabulary of Baroque art—a style known for its theatricality, excess, and grandeur. How do you navigate the line between sincere reference and ironic reappropriation? Is beauty in your work ever a form of camouflage?

My paintings, despite the seriousness of the subject matter, are not entirely serious, I try to make them have a bit of humor in them so that they are not pathetically inflated, so in that respect there is a bit of irony in them. A lot of things in the ornate visual vocabulary of Baroque art just sincerely appeal to me and I use that. There is indeed a lot going on in my latest paintings. There is a certain theatricality and excess in them. I often add element after element, being careful not to cross the fine line after which everything becomes unbearable kitsch. I hope it succeeds. I’ve never aimed to paint pictures whose paradigm is beauty; I’ve usually heard of them as being rather sad or gloomy. But does beauty mask anything? In one recent work, the titular Tiger (The Tyger /William Blake/), which in Blake’s poem is the epitome of evil, is merely a frightened, fleeing animal when confronted with a human being, or a shape that was originally a deadly projectile evolved to become a beautiful flower in one painting, while in another it was already a bird of prey. So yes, there can be evil behind the beauty.