Your practice weaves together painting, sculpture, poetry, and myth into a personal cosmology. In the context of our current theme Gilded Lure, how do you perceive beauty as a seductive force? Can enchantment be a form of camouflage… or a trap?

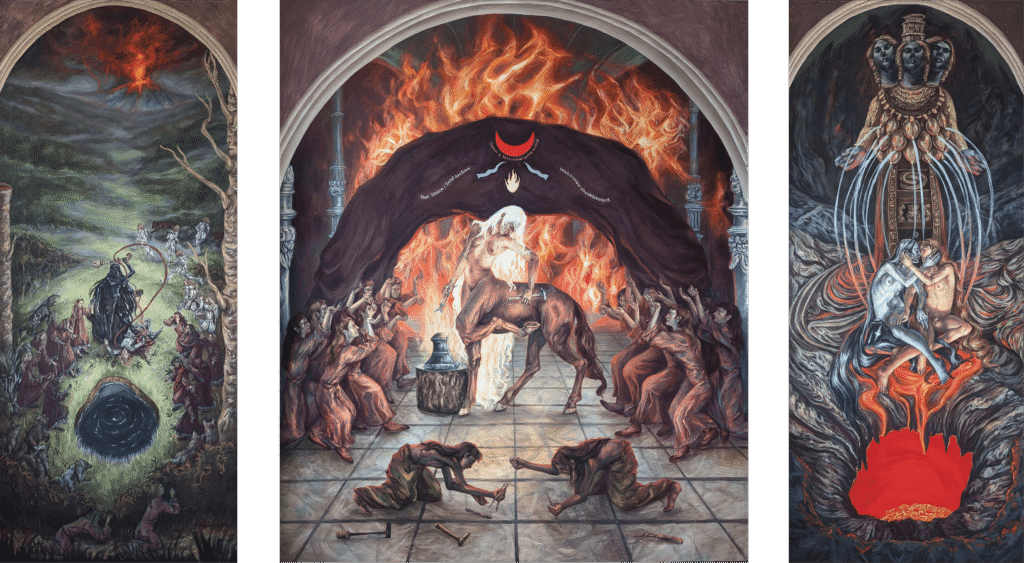

I see my practice as migrating between the beautiful and the not beautiful – however, this is not accomplished by pitting beauty against turpism or introducing direct contrasts into the visual realm of my work. Rather, I feel that I’m stepping into the costume of “beauty” to lean into subject matter that is actually filled with violence and trauma. Storytelling is closely intertwined with the tragic nature of the past and the present (perhaps the future as well, depending on the course of events).

When we look at paintings and engravings depicting what the supposed cabinets of curiosities might have looked like, it’s not easy to resist admiring the beautiful collections of things deemed by someone interesting. The setting for this space, however, is often cruel and embedded in colonial history. I approach world-building and the creation of my own narrative, as a practice full of risk and requiring attentiveness – playing the role of a person between the narrator and the listener. So I’m more willing to use what can be considered beautiful as a tool for subversion and shaking up the order. So, does this place beauty in the role of a trap? I am not fully convinced of this. I feel that a trap could blind a person to what is beyond that layer that might just appeal to somebody. Camouflage, on the other hand, also poses the danger of not getting beyond what is visible.

I have a deep sense that enchantment is more of a reaction to the subconscious. Deep down we know where something is sewn and it shakes us from the inside.

Figures in your paintings seem to drift between worlds – part vision, part memory. Do you see them as messengers, or perhaps as fragments of a larger mythology you’re still in the process of uncovering?

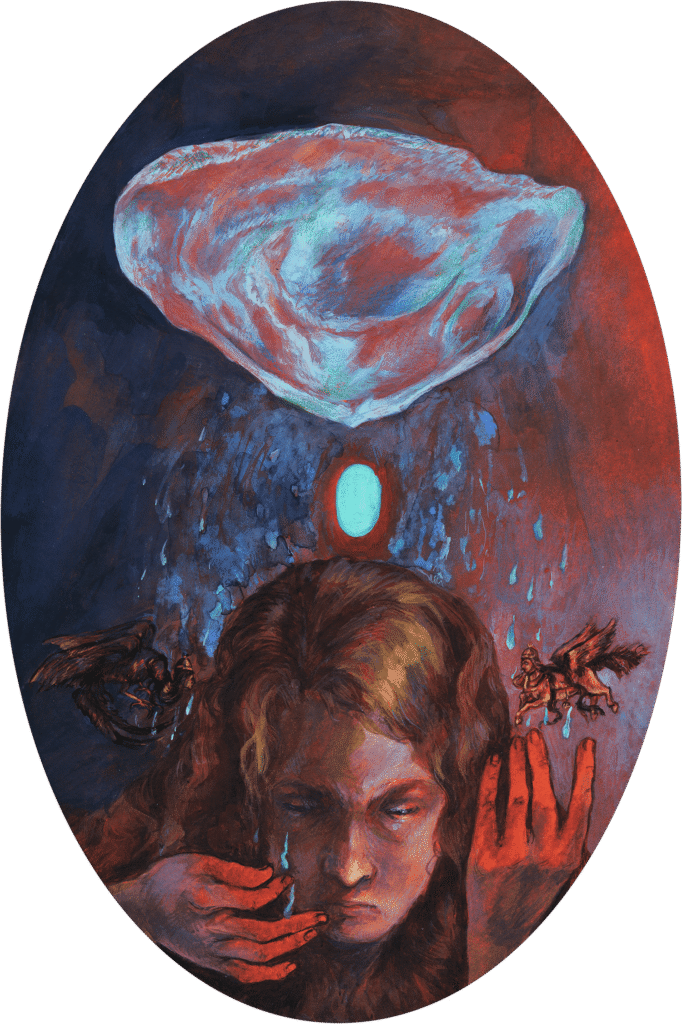

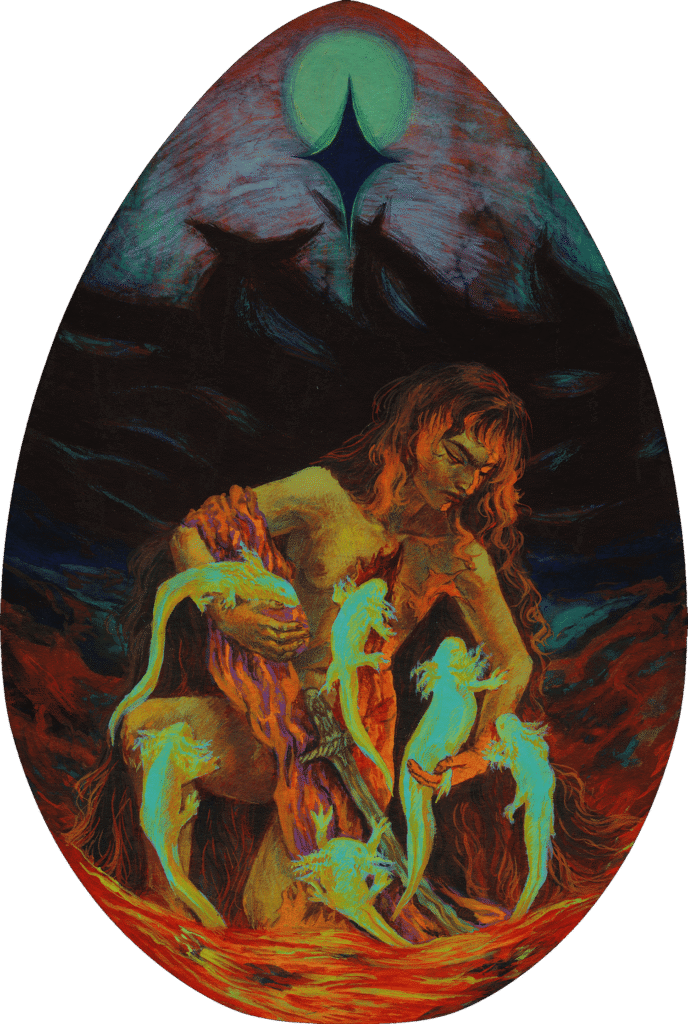

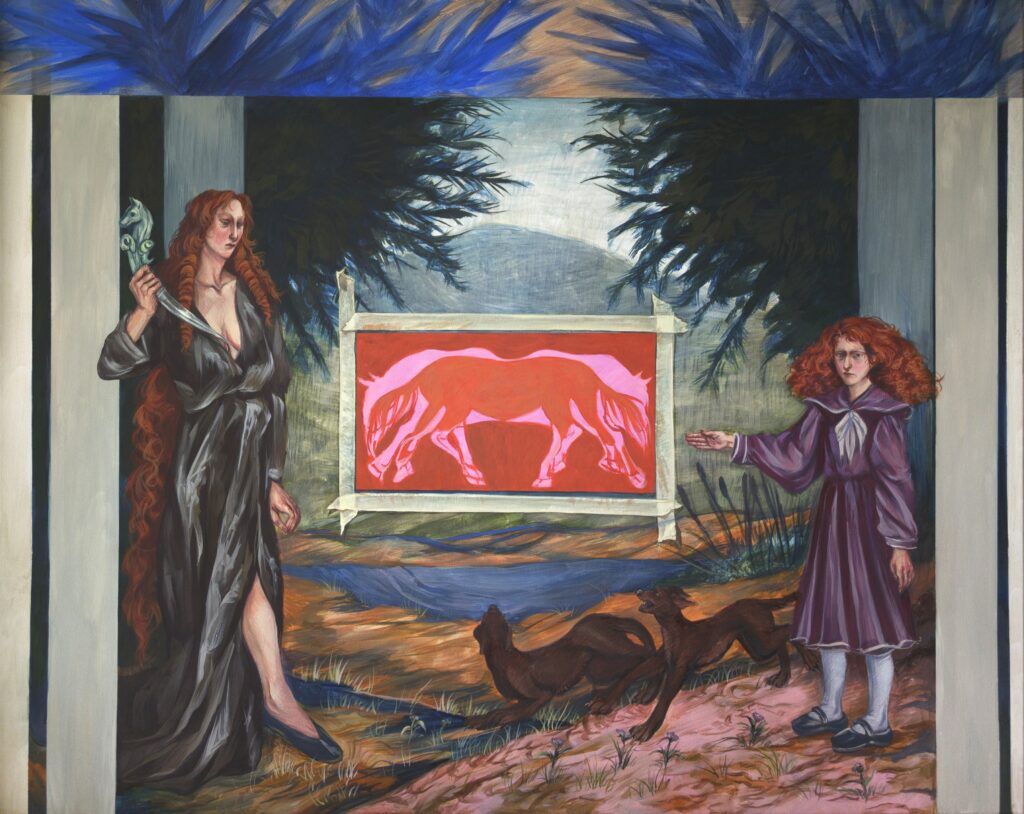

I deliberately detach my characters from specific originals. Nor am I in the habit of capturing, bringing to the studio or transferring every last detail of the models to my paintings. I use such a method primarily because the figures in my works are closer to archetypes, specific sets of traits or travelling images (following Georges Didi-Huberman and his analysis of Aby Warburg’s works), than to flesh-and-blood people. They have many human qualities in them though, as I am unable to turn a blind eye to the somewhat humanly whimsical and complex nature of many mythological characters, but they are not reflected in the real world.

However, even speaking of archetypes, I stress that my archetypes are fluid in nature. A character that is associated in one image with a certain set of characteristics and some specific symbolic situation does not belong to some fixed order. Characters transform and that’s how I capture them – most often at the stage of some kind of transformation. I see them as connectors between many worlds, but I do not give them full power. I consider my vision of these characters as one potential vision of many mythological heroes in one, but not the only one that is possible. This is also related to the specifics of my mythology, because as you say, I am actually still discovering it, and I am unlikely to ever fully explore the whole thing. Such an undertaking is quite impossible to complete. This is not the matter of leaving out some details and individual threads, but the fact that such a world has no end and alternative worlds are always probable.

In your poem-mythology, images evolve and recur like constellations. How do you think repetition, shimmer, or ornament function within your narrative systems? Are they protective symbols or tempting illusions?

For me, such means are primarily part of the narrative. They can be considered one of many tools that tell the story in different ways and introduce new contexts. For example, the introduction of a fragmentary image, a kind of picture within a picture, creates a different narrative area than what does not belong to this space. In the painting “Khavele,” the image in the background is a fragment of the Wawel tapestry depicting the Creation of Eve – the main character of this work is a travelling image strongly associated with the specificity of archetypes similar to the biblical Eve.

Multiplications are a very important element for me with an untoward, in a way subversive nature. On the one hand, they presuppose unity, on the other hand, they are part of multiplicity – they never represent complete, full homogeneity because of the nature of the human hand. Also, ornaments, seemingly mechanical, yet unique in nature, are, in my view, often the most direct transmitter of a fragment or whole narrative. Their specificity, however, within my work is closer to camouflaging worlds within worlds than to illusion.

Your interest in cosmogony feels like a tender rebellion against linear time. In a world that often prioritizes surface over substance, do you see your mythmaking as a way of reclaiming hidden meaning beneath the ornamental?

Most of all, I perceive some kind of defectiveness of linear time at least within the realm of narrating, storytelling, weaving and re-imagining. Reaching back to Jacques Derrida’s hauntology, I find it hard not to point out the rather distressing status of time as we know it. Haunted by what is past and doomed to an equally haunted future – this, unfortunately, is also the result of certain stories not being heard, erased, drowned out or remaining in a closed circuit. What interests me is why we don’t listen to certain stories. Who and what gives certain stories more rights than others?

Our history as a human species is not homogeneous, including in terms of time. So I create cosmogony as a world outside of a clear temporal and historical space, rather as a dialogue between many worlds. However, I feel that the times we live in, paradoxically, despite the technological revolution, once again call for storytelling and a somewhat romantic impulse. For me, the creation of myths is the result of the clash between personal and external space, which never exist in isolation from each other. I am closest to the practice of reclaiming overlooked and silenced stories and myths that require revisiting.

You mentioned being inspired by folk and esoteric traditions. These often carry warnings hidden inside beauty; cautionary tales wrapped in embroidery. How do you approach that kind of coded storytelling in your own work?

I believe that folk traditions are underlain by dread, but not related to horror movies, as is often associated within pop culture. Rather, it is a horror that stems from uncertainty and a certain deafness of history. Perhaps the most tangible warning is the song “A w niedzielę z porania,” which is the oldest surviving Polish song and tells the story of a girl being cast down to hell because of killing her own children. However, I do not see in these contents only a moralizing and warning aspect. For me, such sources are the first and foremost a testimony to an undoubtedly difficult history and part of the force that changed its course.

When I started working on the poem “Z pyętra pyątego”, I came into contact with Gnostic texts, and perhaps it is through them that this transformative aspect of the narrative is most relevant to me. In fact, every story is some kind of code that has different results in reception. It doesn’t even have to have a moralistic nature to do so. Narrative always has a transformative role – it’s part of the language that shapes our world and has more than its share in creating it.

Your figures often seem caught mid-transformation, as if drifting between human, divine, and dream-state. What are the causes of their transformation or is it always myth or story based?

The reasons for their transformation are very complex and depend on the travelling images they embody. However, in a general context, I see the revolutions and transmutations within my paintings as the result of various forms of oppression or opposing the dualization and linearization. The characters I depict transcend time, genre, space and gender. I rarely depict characters that are explicitly gendered, as I constantly move in the liminal space. Likewise, they are not grounded in either humane or divine nature, although individual characters in my textual work have these connections made more apparent. However, I do not consider my textual work to be the only possible version of these worlds, so I do not enforce my legendarium explicitly. The most important thing for me is that I do not associate travelling images with an unchanging and constant nature, but rather with water and fire, which are never completely fixed.

You work across so many media – painting, poetry, video, even sound. Which medium feels the most like a spell, and which feels like a confession?

Painting is the closest thing to a confession for me. In general, the visual arts, from my point of view, most directly affect our consciousness. For some reason we talk about travelling images – the image is an essential part of our consciousness both culturally and in our own imaginations. After all, we dream with images, and even text, in its graphic form, is a kind of image. However, I have the feeling that painting is closer to music than it seems. I have a rather synesthetic approach to sound and treat it in a similar way to visual arts. The text itself is closer to my definition of spell, although it is also part of the nature of my mythological poem. “Z pyętra pyątego” was created at first as a memo for a painting that could be impossible to fully paint. The text is never the most direct medium in nature, but rather requires a certain amount of gymnastics. But I also cultivate a way of writing as if I were painting with words, because I create a distinct dialect and work intensively with wordplay.

For this reason, this text will never become the most direct because of its hermetic nature. On the other hand, however, it is sometimes more intuitive to me than painting, although this is a bit of a paradoxical conclusion in relation to the image. I also think that one does not exclude the other, because each of these fields in me intertwines, and the seemingly unrelated matters coexist in close correlation.

In our theme, we think about the gilded surface as both a promise and a distraction. Have you ever made something you felt was “too beautiful”?

I don’t think I’ve ever made something that is too beautiful. However, I see myself as a maximalist, and while I don’t consider this a bad trait, I think taming maximalism is like domesticating a lion. Sometimes maximalism is necessary for me at some stage of my artistic growth. Other times I turn to a much greater degree of synthesis. I try not to stick to one way of doing things, and go after what the work suggests to me.

What does artistic growth mean to you at this stage? Do you feel called toward new forms, or is it more about going deeper into what you already do?

I’m in my fifth year at the Academy of Fine Arts, so it’s a peculiar time. I feel that things are changing so intensely that there is now much stronger pressure to be ready for anything even before leaving the academy. I don’t think there are artists at any final stage. Art is so changeable that the versions of worlds are really infinite. At this stage I try to listen to what new developments my creative path will bring me.

Looking ahead, what kind of spaces, collaborations, or audiences would you like your work to inhabit in the near future?

I would very much like my works to visit a couple of historical locations – primarily to interact with them, but also because I would like to expand the field of influence of my artworks. It is also important for me to explore the performative aspect of myth-making. I will leave collaborations in the domain of secrets that only the travelling images know.