Your paintings seem to hum with the voices of forgotten proverbs, fractured myths, and ancient echoes. When collecting these stories, what tells you a fragment is worth keeping? Do they come to you as whispers, or do you seek them out deliberately?

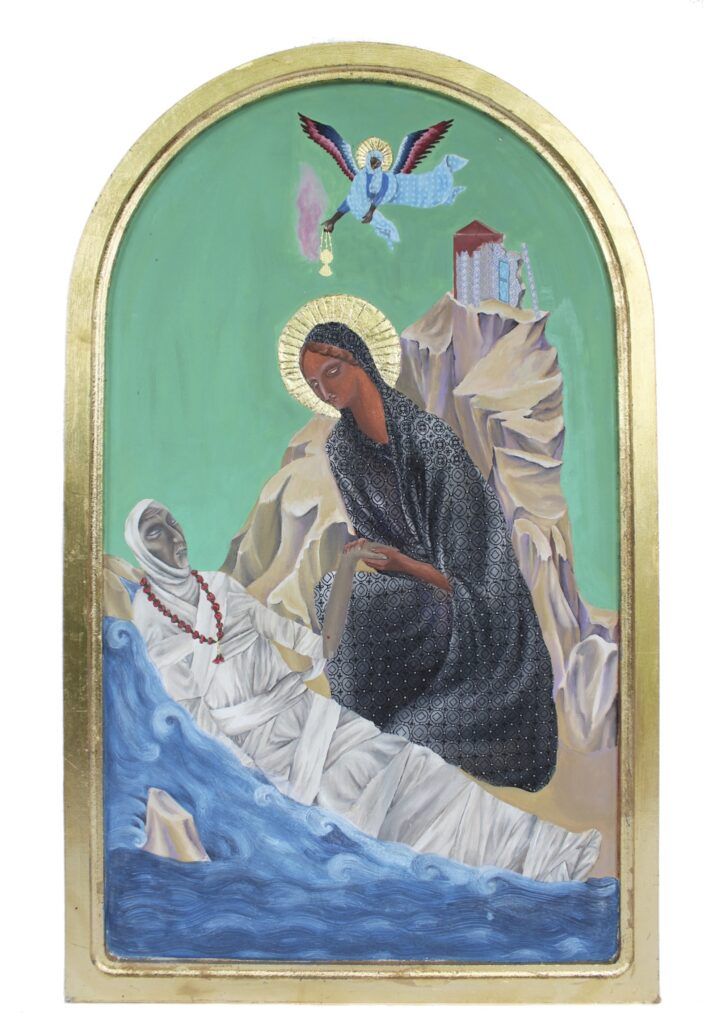

They definitely come to me as whispers – but it’s also true that I’m always seeking them, almost instinctively. I feel naturally drawn to them. Still, the ideas for new works often feel like they fall onto me from above, like something falling out of a balcony onto me. I’ll read something, hear an old saying, witness a ritual or a ceremony, and suddenly a detail strikes me like lightning – I see the work already made. Of course, it never ends up exactly like the vision I had. But that’s where another phase of creation begins, something more parental – that’s a different story. What I’m describing here is like an annunciation. It’s the most thrilling part: that sudden spark. The rest of the time, I’m just the vessel turning that flash into something physical, something tangible.

You’ve described your work as a way of “reading reality” – a reading layered with metaphor, contrast, and mystery. What do you think reality is failing to say out loud that art must whisper or scream in its place?

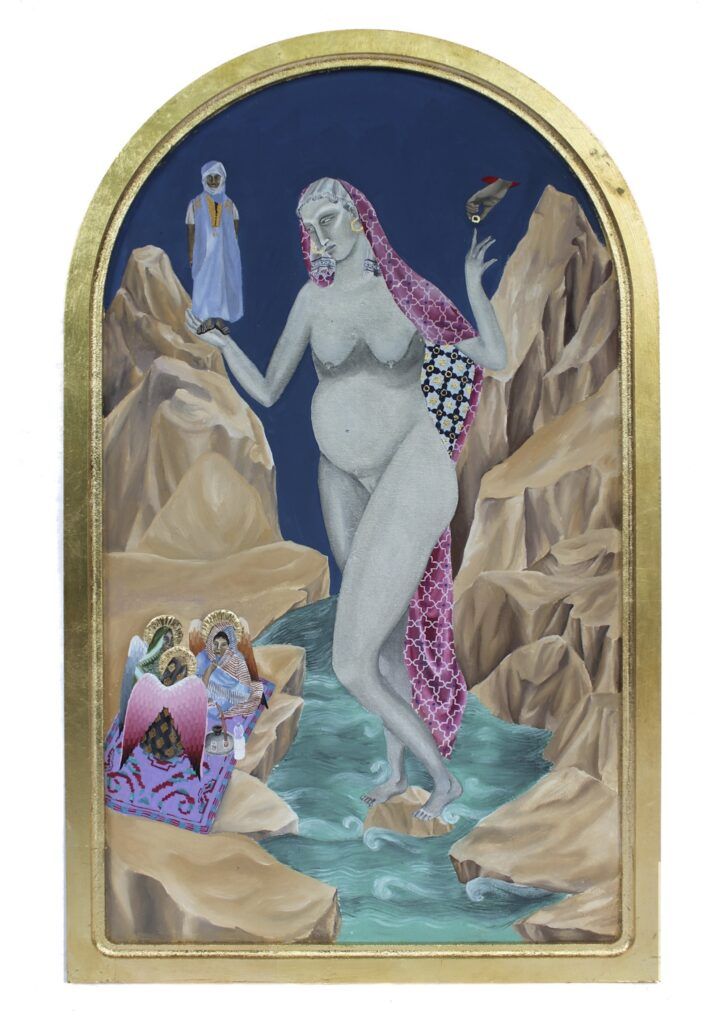

I think what reality, or at least how we tend to perceive reality nowadays, often lacks precisely this: metaphor, mystery, narrative, contrast. I realize I have a miraculous view of life or reality – not in the sense of denying its harshness or cruelty, but quite the opposite. That’s exactly what I want to speak about. I believe storytelling, proverbs, and rituals are ways of narrating life in a miraculous form – not to explain it away or neutralize it, but to see it, and through seeing, to accept it. To me, this is how we make space for reality to remain as unpredictable as it’s meant to be.

There’s something wonderfully contradictory in your images – comfort and devastation, miracle and ruin, sacred and earthly. What draws you to this kind of visual chiaroscuro?

Well, perhaps it’s something therapeutic – a personal attempt to accept every situation in its full integrity and complexity. All pleasant things carry their own shadow. If we avoid that shadow, what we’re left with is just a glare, a blinding illusion. And then, opposites – though seemingly contradictory – often collapse into one another if you look closely enough. Take sacred and earthly, for example: the miracle, I believe, is everything that is earthly.

You turn to the past not as a museum but as fertile ground for rediscovery. In this age of compressed time and flattened difference, what do you believe we’ve most urgently forgotten?

My work is deeply rooted in the past, but not in a museum-like, lifeless way, as you mentioned. My gaze toward the past is alive because to me, the past is something living, something that continues to resonate in the present. The present contains the past. That’s why, in my paintings, time is not linear. It’s more like a container, a reservoir I draw from freely and intuitively.

What I feel has been flattened and forgotten is, as I mentioned earlier, our relationship with mystery. We’ve lost the ability to live with the unknown without needing to dissect or resolve it. I believe mystery is our true vital force. What inspires me most is not the urge to explain everything, but the human tendency to embroider mystery to live with it, to make it our own through storytelling, metaphor, rituals, proverbs, etc.

That’s what I try to do with my paintings: I embroider mystery. Not to erase it, but to give it form.

And it’s interesting that you mention the flattening of difference – my work is, in many ways, an altar to difference. I believe that only by fully accepting both our own differences and those of others can we coexist without erasing our identities.

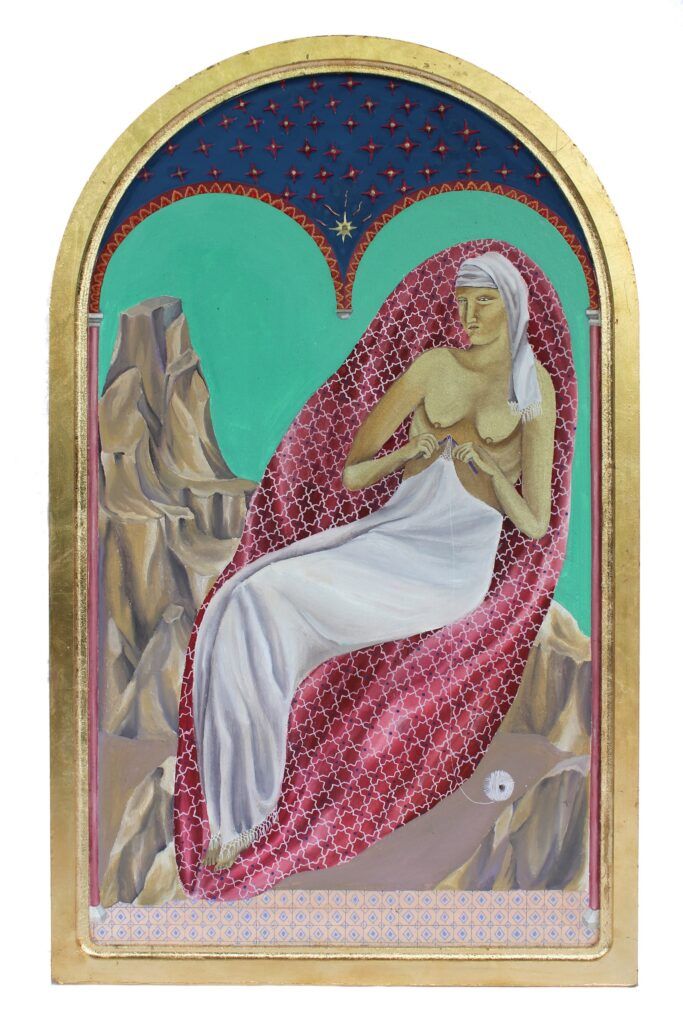

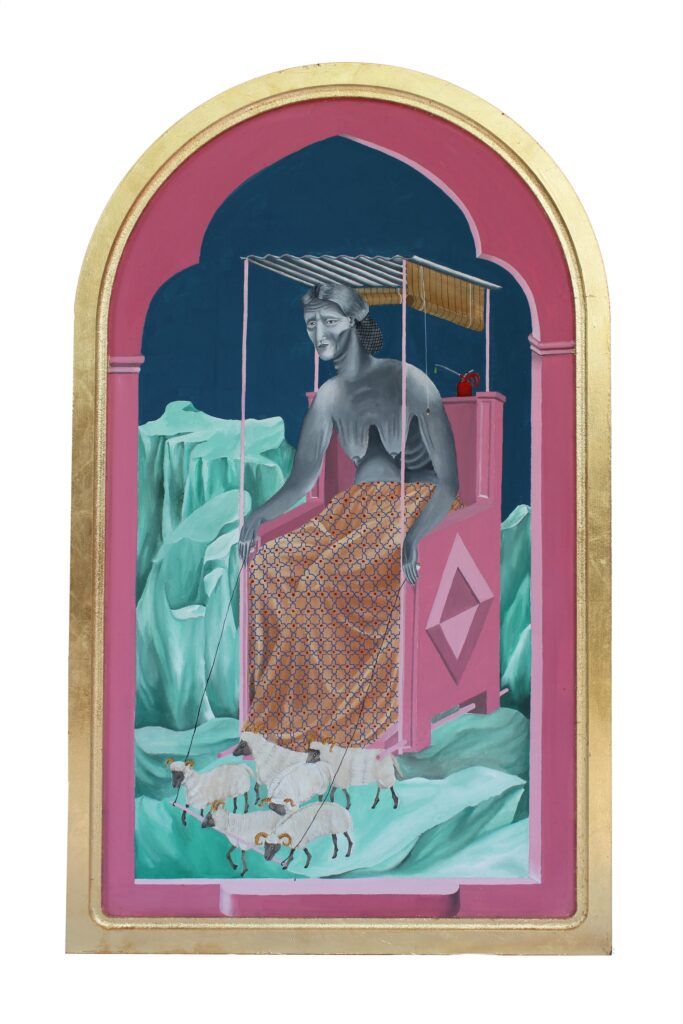

Your use of collage, gesso, and paper mache breathes a textured aliveness into your pieces. Do you see materiality as part of the story you’re telling – something that carries its own kind of folklore?

Definitely yes. I’m deeply fascinated by materials that have ancient roots, or that carry with them a sense of folklore, like papier-mâché, which is often used in fairs, festivals, and popular traditions. It’s a humble material, accessible, unpretentious – and that’s exactly what draws me to it.

Lately I’ve been placing a lot of importance on the support itself. For example, I try not to use pre-made canvases, but rather fabrics that already carry a story: old bedsheets, or handwoven cloths passed down from my great-grandparents. I need the surface I work on to have a story itself, to be alive in its own way. I want it to mean something before I even touch it.

The aesthetic lineage you cite – Giotto, Martini, the Lorenzettis – is rooted in storytelling, in devotional intensity. What kind of devotion do you think contemporary art still allows for – or perhaps, demands?

I believe the work of the artist is one of the few – if not the only – professions where everything is allowed. I honestly don’t see much difference between now and a thousand years ago in that sense. The changes are economic, social, cultural, historical – but at the core, the artist must have the space to represent anything they want, without limits.

I don’t believe in setting boundaries for artistic practice. Maybe it’s a simple answer, but what I love most about painting is exactly this: I can paint whatever I want. Anything is possible. And the message – whether intentional or not – can be shared, rejected, misunderstood, embraced. But in art, it’s allowed.

Many of your figures appear suspended between centuries, carrying small relics of lost rituals. Are these characters fictional, or do they carry memories of real people, spirits, or parts of yourself?

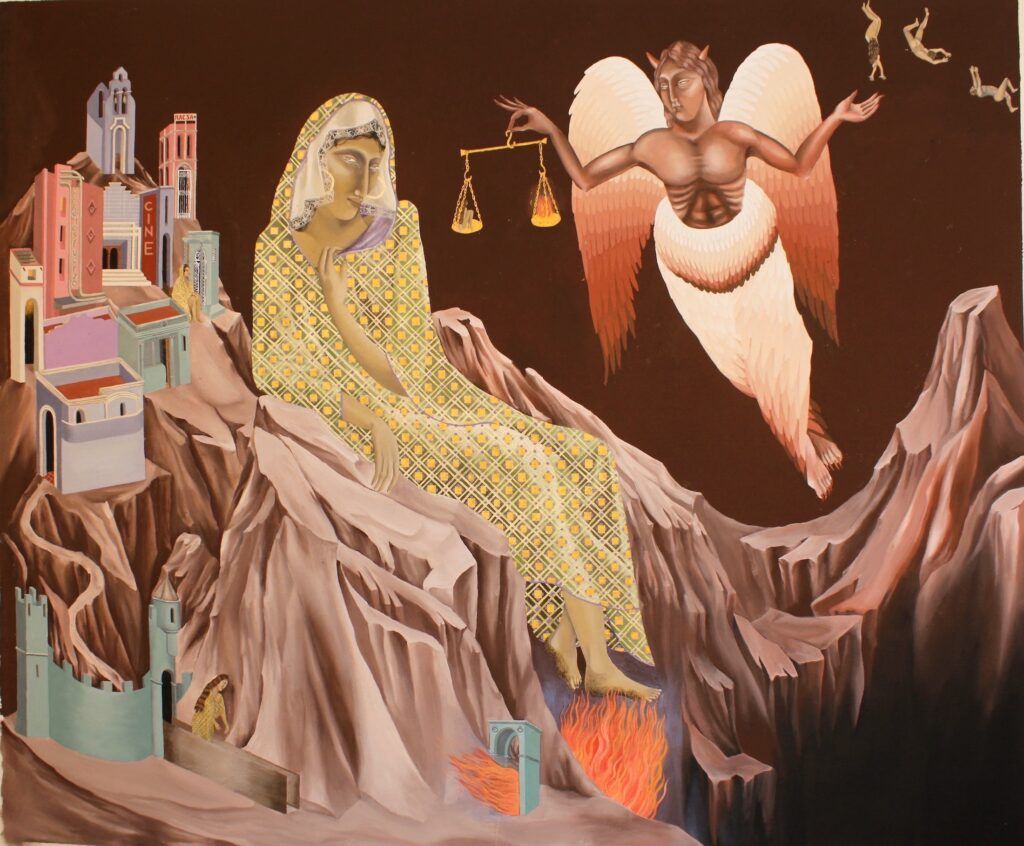

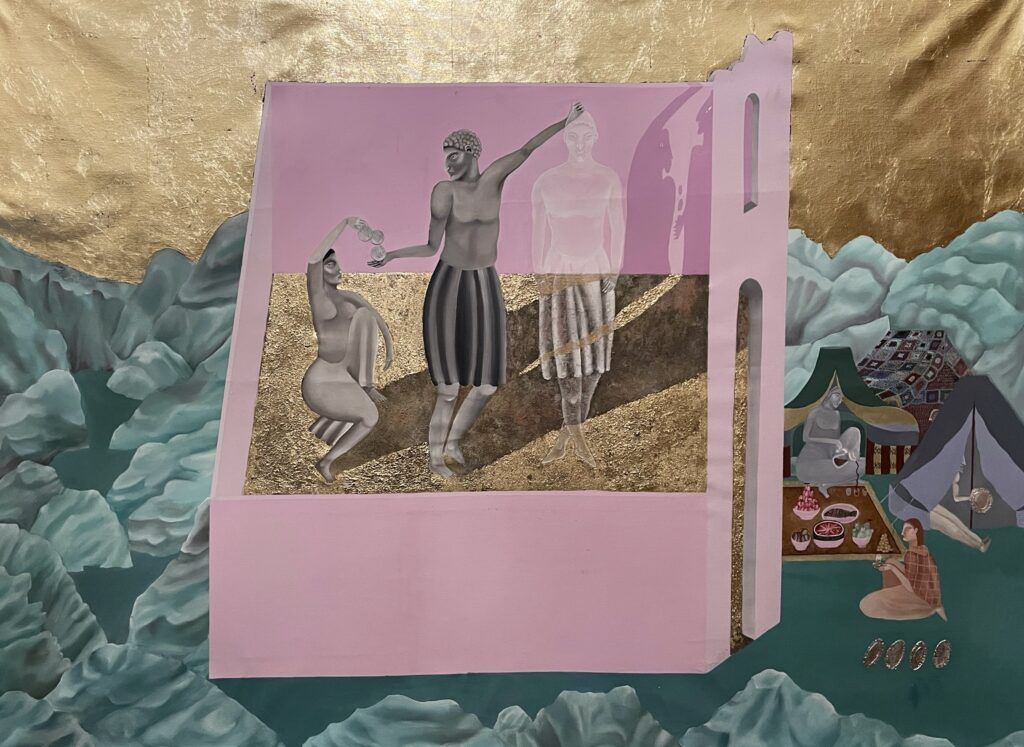

The characters in my work are, first and foremost, portals – gateways into the world that the painting, as a whole, evokes. The human figures aren’t the main characters. In fact, nothing is the main character. It’s more of a collective effort, a kind of teamwork among all the elements. Maybe that’s why my paintings often resemble theatrical sets.

That said, the human figure is what I love painting the most. And yes, there are faces, bodies, real people who, in the middle of a crowd, somehow “call” to me – and I feel I have to paint them. So I often depict real people, although always reimagined – because at the same time, they are many different versions of myself.

You’ve spent time in Italy, Asia, Australia, Senegal, and beyond. How have these different geographies shaped your visual vocabulary, especially your sense of what is sacred, symbolic, or invisible?

Many places I’ve lived in or traveled through have left a deep mark on my work, both visually and symbolically. There are different layers of “journey” in my paintings. One is the idea of multilateralism – I often bring together details, objects, or symbols from different cultures in the same work, allowing them to live together without erasing one another.

It’s also a way of comparing what might seem like opposites, cultural differences that, deep down, are rooted in the same human needs. During my travels, I’ve realized that across the world, the core impulses are often the same. The differences lie in how each culture responds to those impulses. So in my work, I like to juxtapose visual elements from different traditions – sometimes they may seem dissonant at first glance, but in the end they create a strong aesthetic cohesion, a visual harmony that symbolizes the deeper unity among cultures.

As for the symbolic, sacred, and ritualistic aspects: those are the ones that attract me most. I’m deeply drawn to ceremonies, rites, small everyday gestures that echo something timeless and mysterious. I often work with proverbs, idioms, traditional customs, superstitions – what I call cultural gems. These expressions carry a kind of sacred power, even in their most humble, daily form. They fascinate me, and I tend to weave them into my work.

Senegal, in particular, has had a strong impact on me. What struck me there is what I would call a joyful sacredness – something that lives both in people’s attitude and in the country’s aesthetic. It’s something I return to often in my painting, not only because of the visual richness, but because of how deeply it resonates with the themes I explore.

If there is an “inscrutable dimension of reality” threading through your practice, as you say – do you consider art a portal, a mirror, or something more like a spell?

Honestly, I feel that art is both a portal and a spell. It’s a vehicle that takes us toward that inscrutable dimension of reality, but in doing so, it performs a kind of magic – that’s where it becomes an incantation. Art draws from reality, yes, but it transforms it, pushes it elsewhere, gives it a new shape. In that act of transformation, it creates something that didn’t exist before – and that, to me, is a form of miracle.

Looking forward, where is your work pulling you? Are there new stories, materials, or forgotten deities waiting to be unearthed?

I like to believe that what fuels my work is that inexhaustible source of mystery that is, in my opinion, the very vital force. In this sense I feel like I am caught by new inspirations and new stories that make their way into my works – I am not even the one looking for them, I stumble upon them and they ask me to collect them!