Zu Kalinowska

Mortal Shell

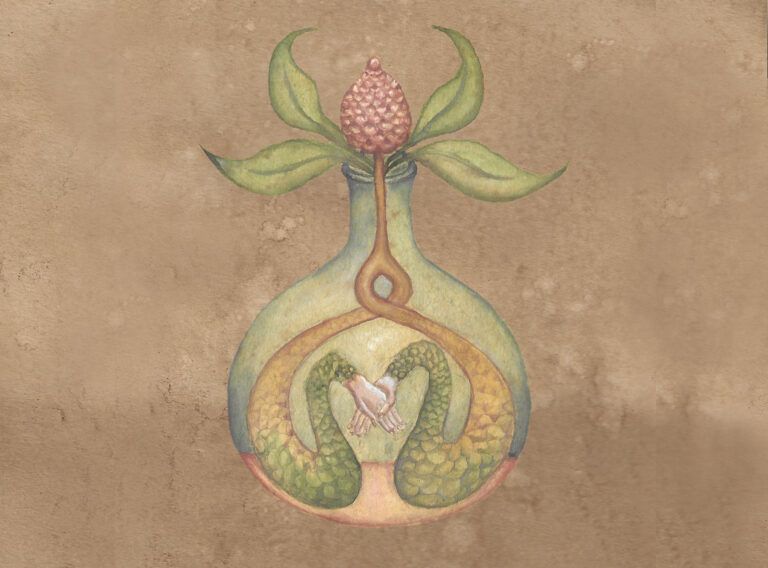

“Is it possible to create some sort of intimacy osmosis?” Posing this question as part of her exhibition at gr_und, Mortal Shell, Zu Kalinowska places vulnerability at the centre of her new body of work. For while intimacy sounds soft and sweet (or feels like stroking hair), when you consider how we actually reach (for) intimacy, it is often defined by something other than closeness or even love. It is necessitated by risk: of honesty, of being accepted, of falling in love. Intimacy cannot be cast in stone or concretised. It requires a continuous relational openness – sometimes prompting somersaults, sometimes tripping us up, bruising us – and it is therefore, to my mind at least, defined by our willingness to enter into a state of vulnerability.

I like the idea of intimacy osmosis, molecules spontaneously moving between us through permeable membranes, without thought, with instinctive reason. Equalising the solute concentrations on the two sides of our respective insides. Where touch speaks louder than words and turns us into willing particles of matter, seeking exchange. Searching out equilibrium.

Using both real and synthetic hair, Kalinowska’s sculptures bring together the natural and unnatural – an osmosis of sorts. She tries to determine control over it: plaiting, twisting, coiling it into shape; dying it with different inks, pigments and paints. In turn, her forms become their own organisms, which animate space: protruding, undulating and curving, surprisingly unnerving in their biomorphism. Take, for example, Occam’s Knot (2021), which is reminiscent of an embryonic creature, tucked away, embracing itself. Blonde hair emerges from its gentle curves, sweeping and falling. Orange woven hair cast in resin recalls a sea anemone’s tubular body with soft internal organs. There is the temptation to prod, grip or stroke it, to work it out, a tactility born of its material intricacy. In reference to Occam’s razor, a scientific method that says any accepted explanation of a phenomenon precludes an incomprehensible number of possible alternatives, this form prefers mutability.

Apostolic Hygiene (2022) is its own strange show pony: two overlapping limbs wrapped with reams of blonde hair – any equestrian dressage expert would surely salivate at this sight. Yet it is remarkably aggressive in its elegance, shooting out from the cobblestone floor. With the title’s allusion to the role of women’s hair in the Apostolic Church, which should not be cut, the sculpture’s locks are pulled tight, belted and clamped in a kind of controlled glory. Crowned with two stoppers (shells, hooves?), Kalinowska has embedded braids within resin that is set and repeatedly polished. Fossils, preserving time. The woven strands are echoed in engraved metal, reminiscent of pearls of wheat – perhaps another sideways nod at religious symbolism, this time the Parable of the Grain of Wheat, a Christian allegory of resurrection. At once organic, machine-like and animal, the work is both alluring and bizarrely grotesque. These are forms that simultaneously seduce and repel, binding our own responsive bodies in a state of uncertainty, willing us to both grasp at and grimace in the face of improbability.

Hair is indicative of intimacy. We caress the hair of our loved ones (or perhaps even clutch it, gently pulling). Once cut, it remains as a marker of time, rich with the colour and softness of the past. Kalinowska cites “the memory of hair. The phantom touch of a stray hair on your arm.” What it felt like to caress you. In this sense, hair is intricately tied to time. It holds time once severed from the body, but binds us to time while we are with it. It fades, greys, thickens. It gives us away. A work such as Portrait (2020) speaks to the slow onset of age, which we try to cover up amid cultural touchstones that elevate youth – Kalinowska’s grey, by contrast, descends from the roots, earthbound, held in place by plastic that will stand the test of time.

In a world obsessed with impossible tropes of beauty, as epitomised by hair, Kalinowska questions the idea of preservation and the inevitability of change; the mortal shells that remain when we strip it all back; the need for ontological fluidity so that we might last, becoming more than just human. The Softness of the Cold Shoulder (2022) is its own otherworldly anthropomorphic spine. Concurrently fossilised and futuristic, its intricate multicoloured vertebrae are connected with a mane of hair that flows from ceiling to floor. This is a prehistoric being continuously observing, mutating, adapting to its surroundings. Seen in this light, intimacy is perhaps parasitic, an organism that watches, waits, learns how to survive, lives in symbiosis with another at the expense of a host, always modifying to escape death.

Kalinowska’s works, however, are not a macabre exploration of death or the finite nature of being human. Rather, to my eye, they are a plea for pleasure in the face of our own mortality. They are undeniably sensual – kinky, even. As she says, “the making of these sculptures needs so much touching: sanding, rubbing, caressing, washing and sanding again. I often ask myself if it’s possible to transpose intimacy into an object, and if that intimacy can then be felt by the viewer.” These works have a material resonance that appeals directly to our sense of touch and wanting to be touched. And it is perhaps in this sense that some of these works embrace an aesthetics of sex toys; shapes that cheekily oscillate between a minimalist wink at purified geometry and a gorgeous lexicon of ropes and whips and butt plugs, didoes, garters and nipple clamps, bars to grab onto while you’re being fucked. They long for the push and pull between vulnerability, control and release, and the undeniable primal instinct of wanting to merge with someone else. La petite mort, which momentarily takes us beyond our own consciousness and into fluidity. Intimacy osmosis.

—By Louisa Elderton