After “A Report to an Academy,” you are once again returning to Franz Kafka’s work. What draws you to his writing, and why did you choose to adapt “In the Penal Colony” this time?

Both A Report to an Academy and In the Penal Colony are short stories and both are deeply concerned with looking and being looked at. In A Report to an Academy, an ape has a lecture in front of an academy of scientists, whereas In the Penal Colony a traveller is sent to a penal colony to witness the execution of a soldier performed by a machine. In my theatre practice, I am constantly dealing with the gaze between audience and performers, it’s one of the materials I work with. This is probably one of the reasons I am drawn to these texts by Kafka. In the Penal Colony examines more specifically what it means to watch the suffering of others. This topic has been on my mind a lot in the past few years: in my private life, in regards to my own media consumption, and as a broader social question in regards to the medial handling of the multicrisis the world is currently facing: what am I looking at and how can I connect to what I see? This is an unsolved question for me and one of the starting points of the concept for this show.

Your new project examines the phenomenon of spectatorship and the observer’s responsibility. How did you approach this complex relationship between the viewer and reality in the play?

I was interested in creating an execution machine for the stage and to consider it as the main attraction of a staging. Executions used to be popular public events, they were considered cathartic entertainment watched by large crowds. In Apparatus, we are trying to examine what this could mean as a reference point for a stage piece. In classical theatre architecture, the convention of the central perspective in a dark auditorium offered audience members an illusion of watching without actually being present, as though they were invisible spectators without any influence on the situation they were witnessing. The protagonist of In the Penal Colony watches the executions in the colony in a similar fashion. He does not consider stopping what is happening in front of him, to save the victims: he feels as though his role of spectator does not allow for an intervention and he refuses the idea of bearing responsibility for the situation as he does not believe he is part of it. His gaze in a way distances him from what is happening in front of his eyes. Our piece tries to play with this paradigm.

In “Aparát,” the execution machine, the power apparatus, and the apparatus of gaze all play significant roles. How did you work with these different layers in the staging?

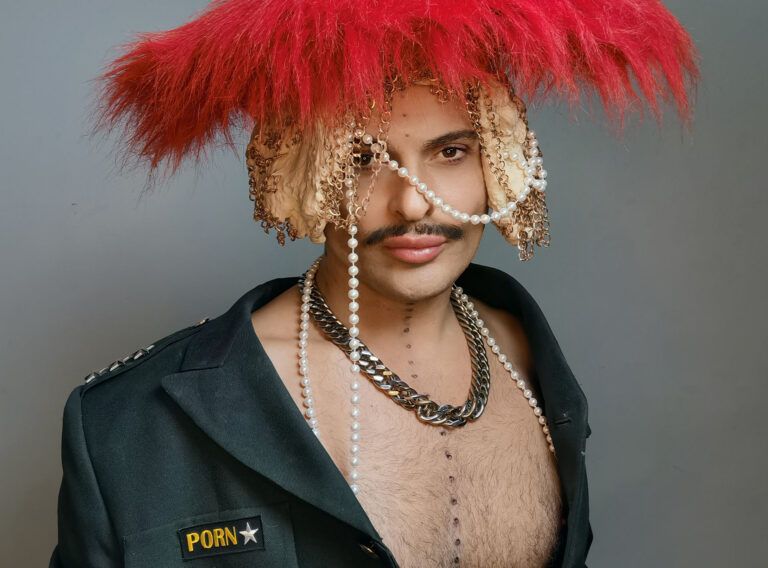

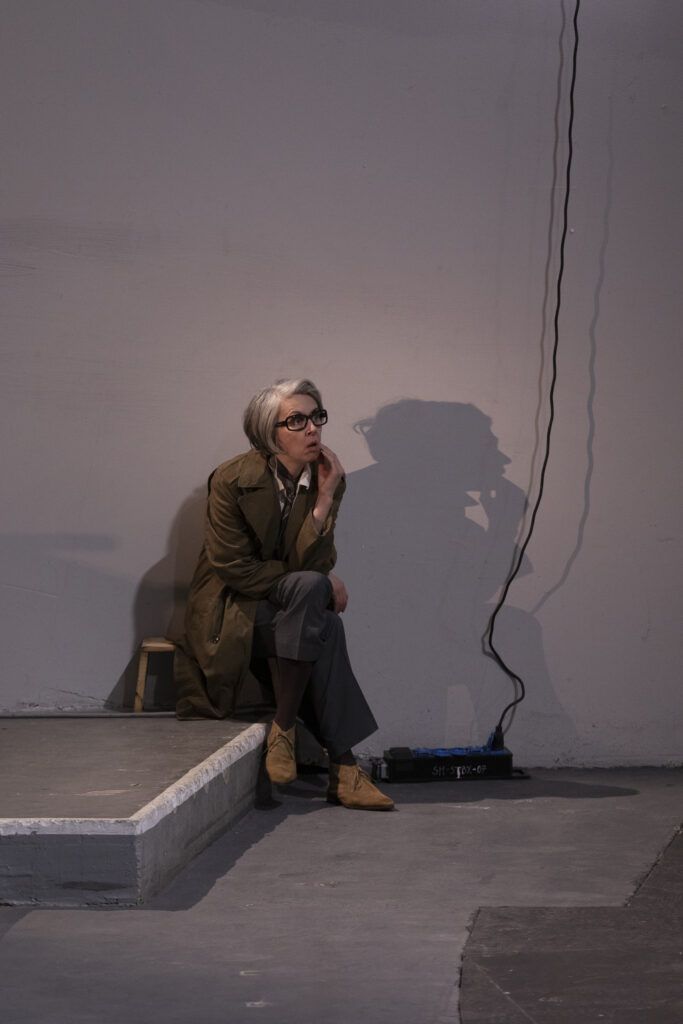

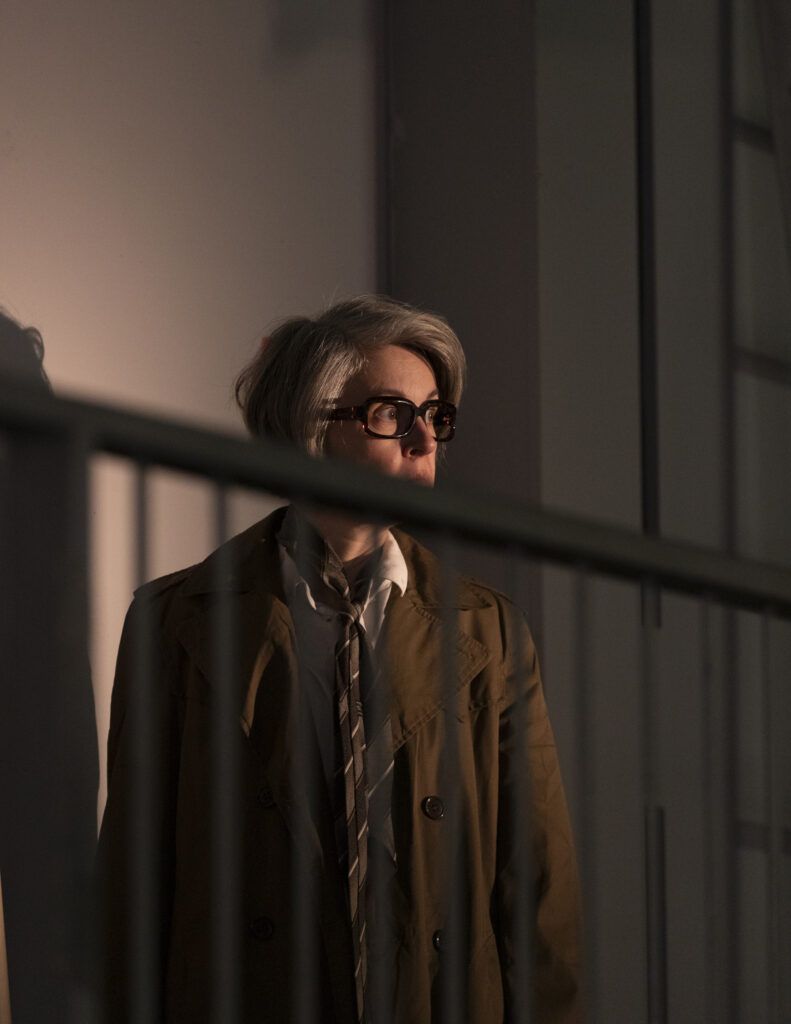

One of the starting points of our work was the concept for the machine itself, which I developed with set designer Pavel Svoboda. We knew that we wanted the apparatus to be the central point of the show and we were inspired by very different sources: construction plans for guillotines during the French revolution, the plexiglass box in David Lynch’s third series of Twin Peaks or the work of artist Rebecca Horn, who spent many years creating beautiful sculptures inspired by machines. A second step was the development of a compositional concept for the show with composer Christoph Wirth; investigating what the sound scape for the show would be, what the inside of the machine might sound like or the environment of the penal colony. Our cast is made of two actors, Ivana Uhlířová and Jakub Gottwald, who play the Traveler and the Officer, one performer, Pasi Mäkelä, who is cast as the Condemned, and Vojtěch Šembera, who is an experimental singer. Christoph is currently writing a composition for him, his character is functioning as the voice of the machine in the show, the voice of the law that Kafka depicts as fundamentally illegible.

The narrative explores the transformation of the officer from judge to condemned. How do you want the audience to perceive this shift in roles?

In Kafka’s story, the officer is deeply linked to the execution machine: he was one of its co-creators and whilst he prepares every execution and functions as a judge in the penal colony, he is envious of the executed and their experience, which Kafka describes as a 12-hour long transcendental journey. The officer wants to experience this for himself, he wants to become part of the machine. Once the apparatus malfunctions, he offers his own body as a demonstration of the machine’s greatness, but also as a treat for himself. His sacrifice is self-serving. In our staging, the execution scene of the officer is accompanied by an aria; it’s a dream-like scene. The performers go through several shifts of roles during the show, this is one of them. They are all connected to each other and to the machine as well; it’s a bit as though the machine were a fifth character.

You collaborated with set designer Pavel Svoboda, composer and sound designer Christoph Wirth, costume designer Patricia Talacko, and dramaturg Ján Šimko. How did this creative team influence the overall vision and execution of the production?

A staging is always a collaborative effort. Pavel, Patricia, Christoph and Ján are co-creators of the piece and so are the performers, our practices are interwoven during the rehearsal process. It’s the first time I am working with Ján Šimko and Vojtěch Šembera, but everybody else on the team is someone I repeatedly work with. I studied directing at DAMU and have been working regularly in Prague ever since, albeit a little less in the past few years. I am thankful to be able to return to Prague, to Studio Hrdinů and create this show with this specific team, it’s a privilege.

Can you share more about your directorial process? How do you navigate the balance between text, visual aesthetics, and soundscapes in your productions?

I usually start to work on my shows with an analysis of the space and I try to find a basic situation or metaphor for the gaze between audience and what they are going to see. Everything else develops based on this decision. In this staging, we work with a huge object in the centre of the visual field of the audience and with a voice-over of the text; except for one scene, there is no spoken word on stage. This means that text, staged imagery, as well as soundscape and composition develop independently of each other, they follow different rhythms and temporalities and each of these elements stands on their own. Sometimes, they come together, but they also create friction and absurd situations. And my directing of the performers thus has a choreographic quality, a focus on movement.

Your work spans spoken theatre, musical theatre, opera, and radio. How do these different forms influence each other in your creative practice?

They definitely influence each other! I studied classical theatre directing and my background is in that field and in playwrighting. I have been working a lot in contemporary opera in the past few years though, as a director and librettist, mainly on the development of new operas with contemporary composers and this has shaped my practice in theatre as well, especially the work with voice. In my theatre shows, the spoken voice is usually stylised in some form, it comes from unexpected sources, is slowed down, sounds like an aria or is unintelligible – there is usually some kind of obstacle to verbal communication. In the case of Apparatus, the spoken voice is a recording that the performers hear during the show, like a fairy tale, in which they themselves almost don’t speak. The whole show is like a dream in that sense; a dream of the machine.