The photographs and texts (authentic smartphone selfies, Facebook statuses, diary entries and the goodbye letter) that make an appearance in the Chimera series must’ve required a large portion of trust and intimacy between you and Gabriela. How long have you known each other?

Long before her transition, Gábi used to be a classmate of my ex-husband at a grammar school – they’ve known each other since they were twelve and used to spend a lot of time together. The moment we moved to Prague with my then husband seven years ago, they got in touch again and she (still male-presenting and under her birth name at that time) started to hang out at our place a lot. Then came a time when the visits ceased and we knew something was up and after a month, my husband received a message that she needs to talk to him. We were wondering what’s happening as she was always eccentric and coming up with unbelievable ideas but none of us expected what the news was. Frankly, I was fascinated by the notion and immediately thought that it would be amazing to document such a transformation of someone close to me as I was always drawn to things and people outside of the box. Norm-breakers, if you will. And because Gábi has always been a natural-born exhibitionist, she enthusiastically agreed, more or less. That was something new to me as I’ve mostly encountered reluctance when doing documentary work with people before – not many are overtly happy to be photographed in their day-to-day lives. But Gábi really enjoyed herself and these moments were wonderful for me as she allowed me to do what I wanted without objections.

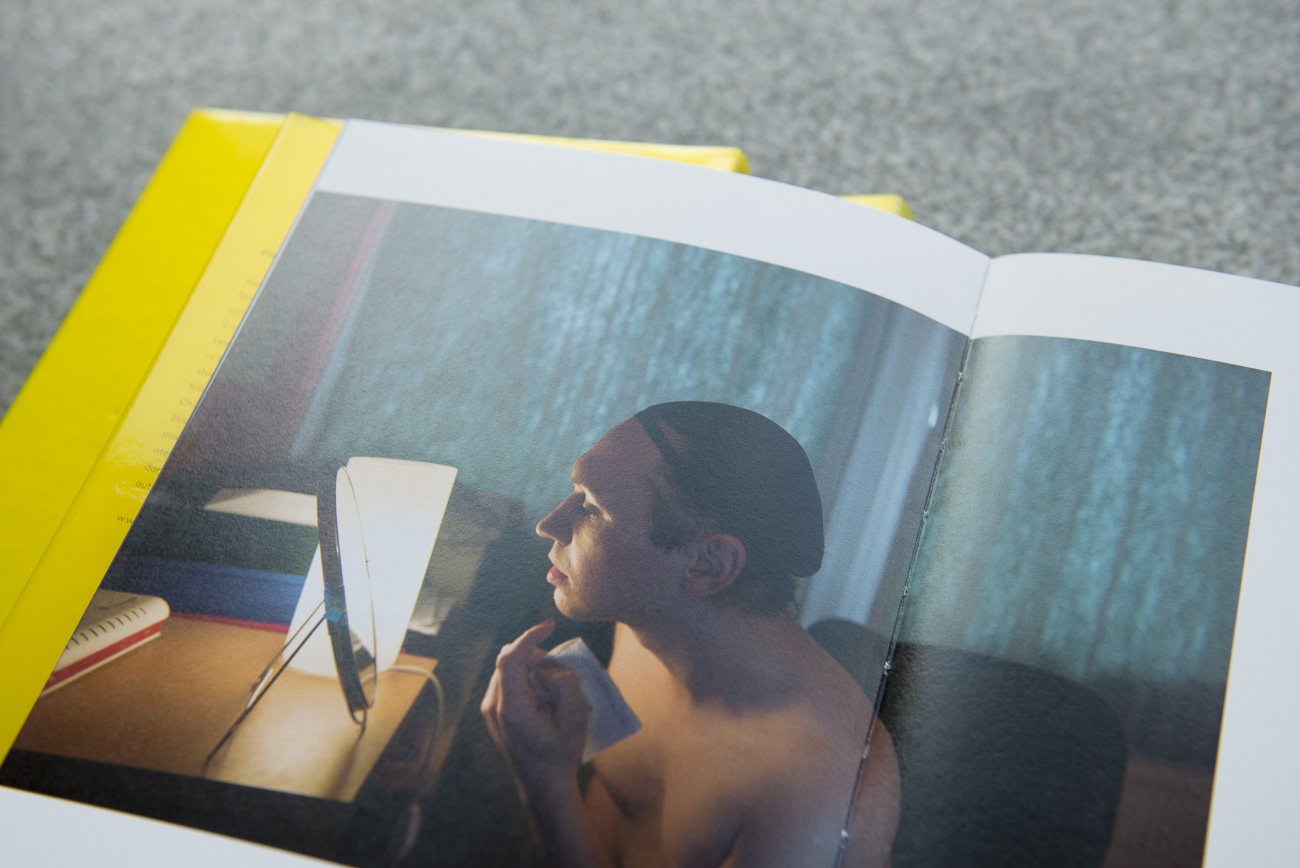

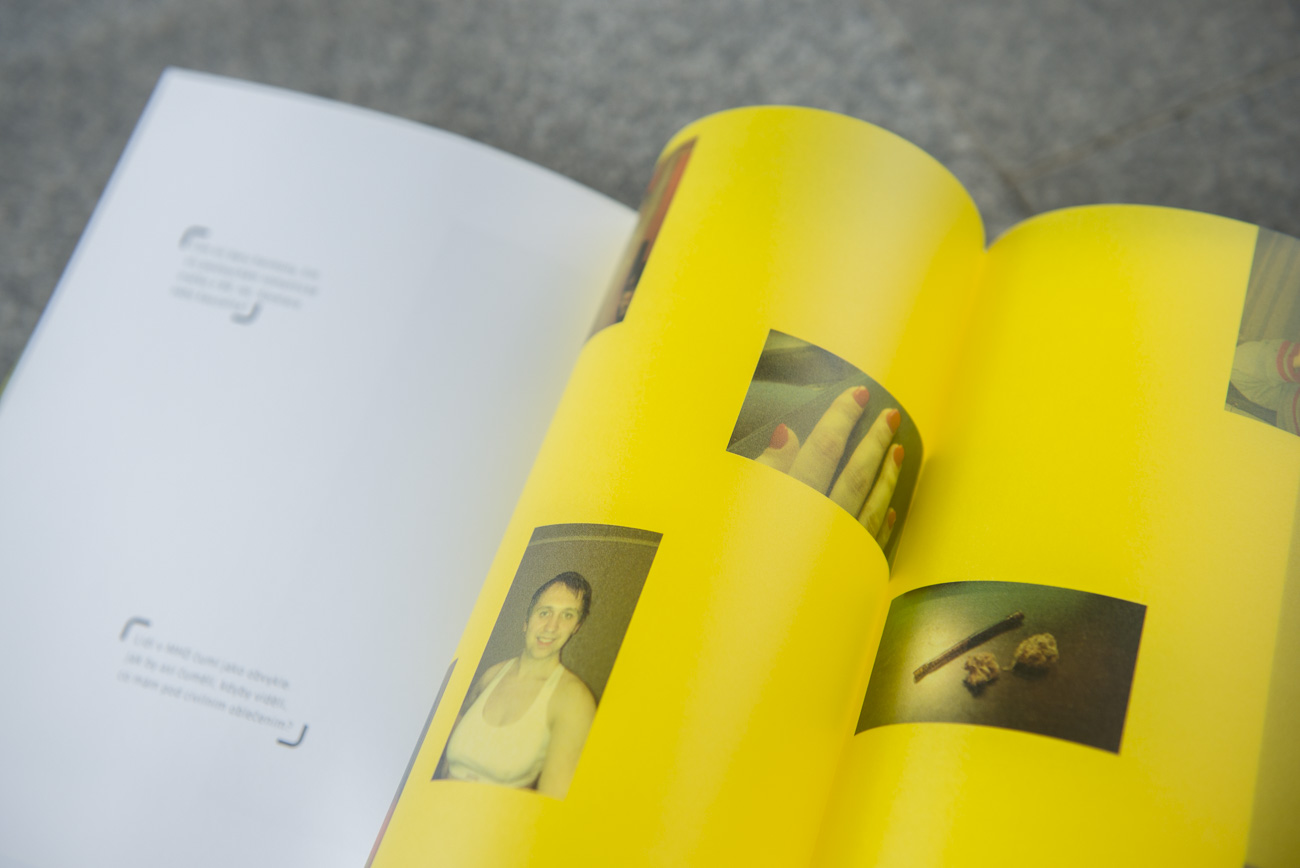

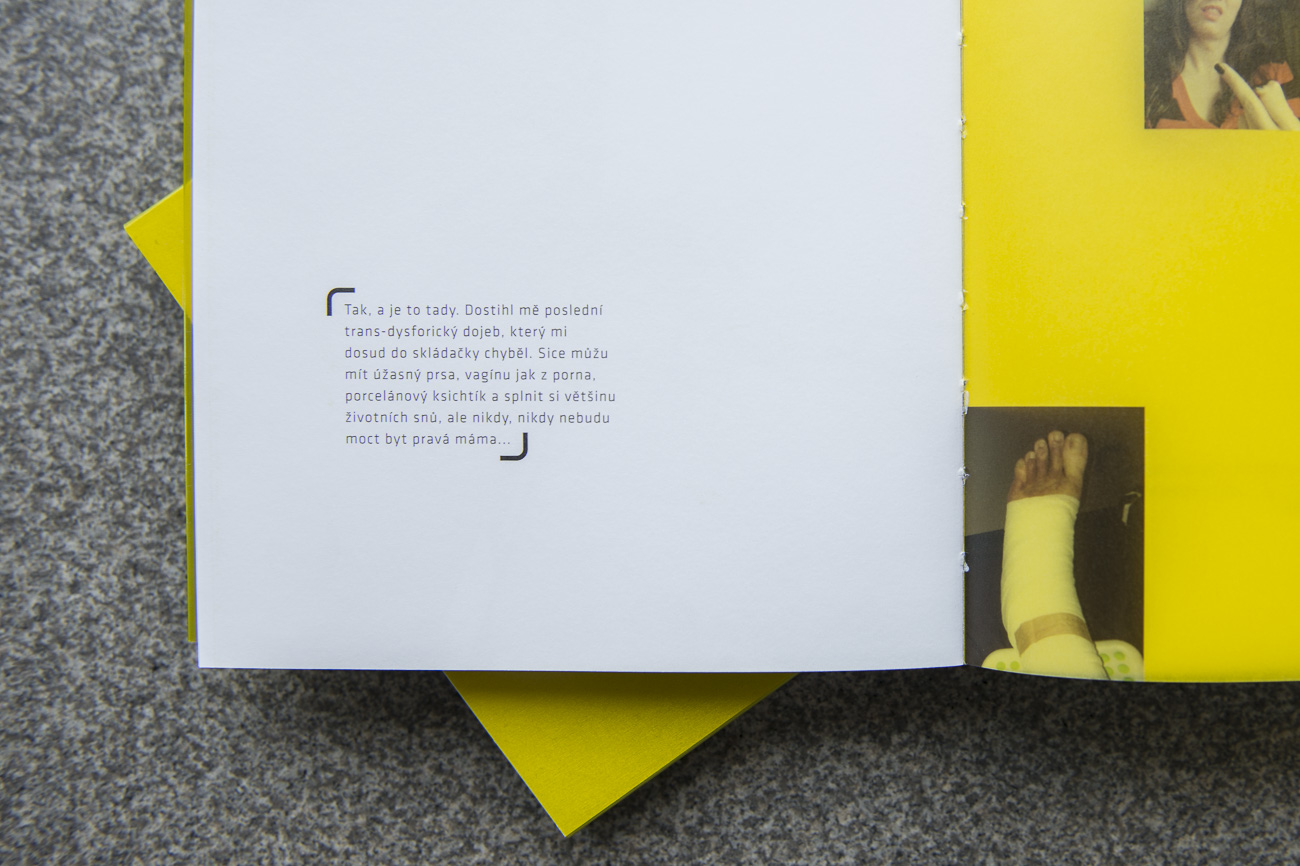

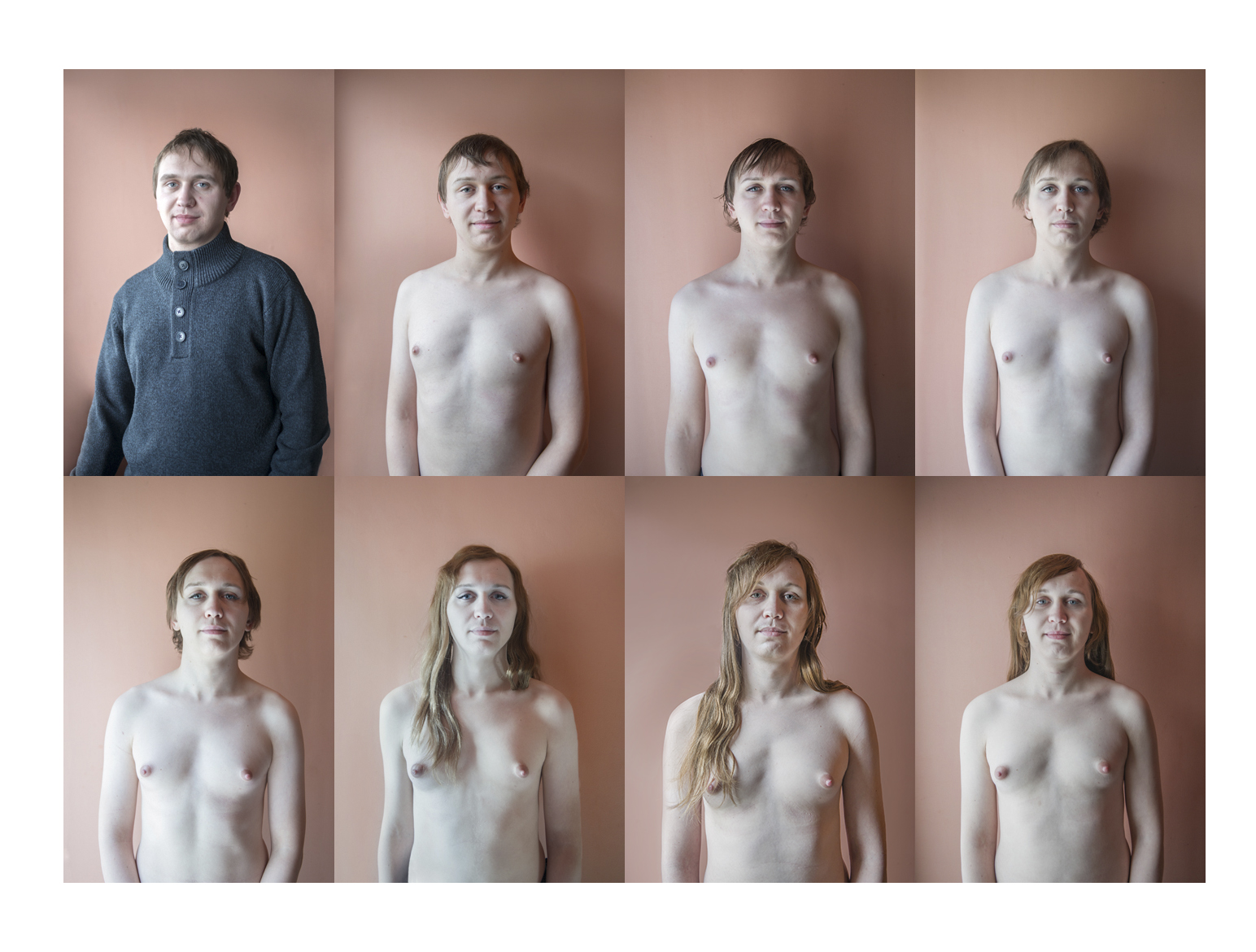

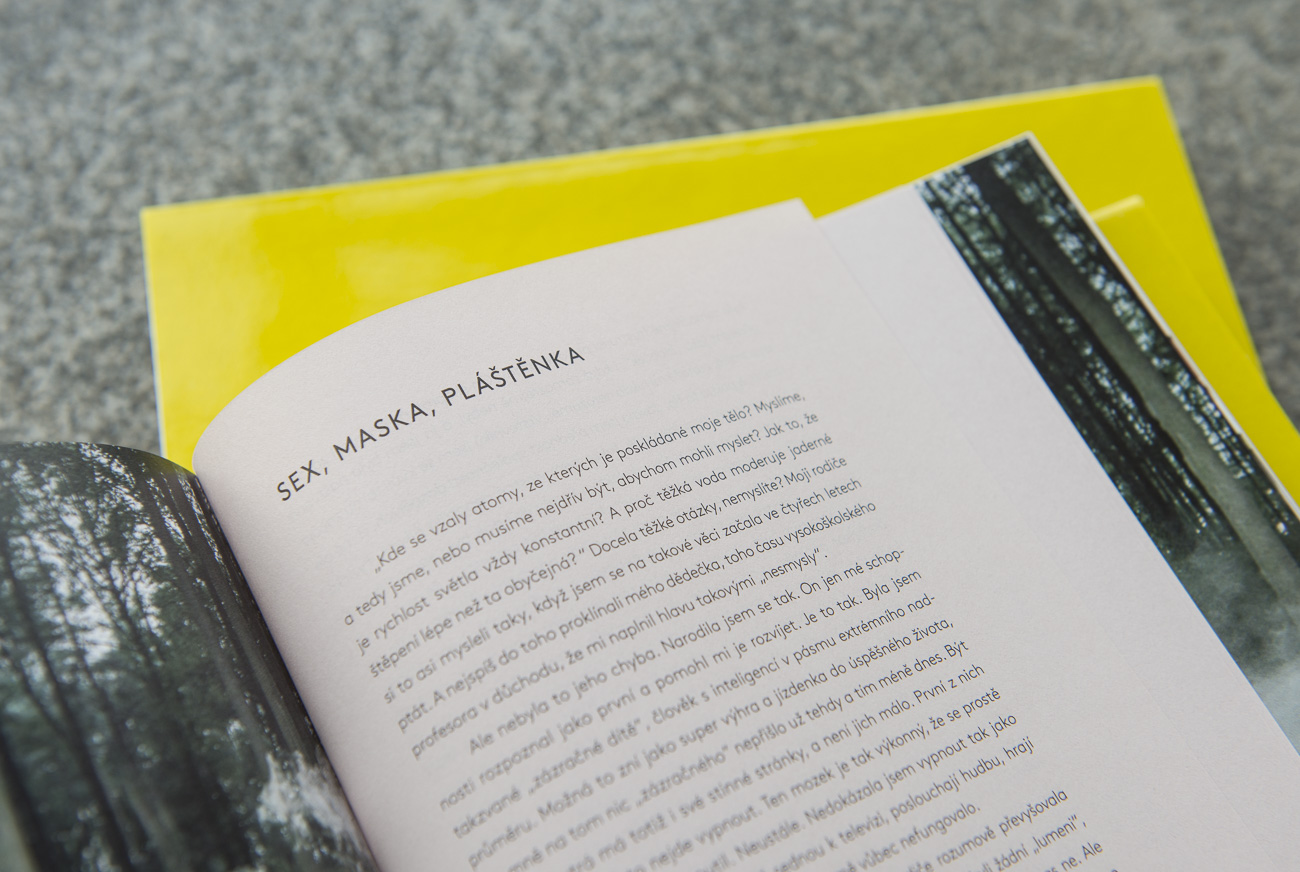

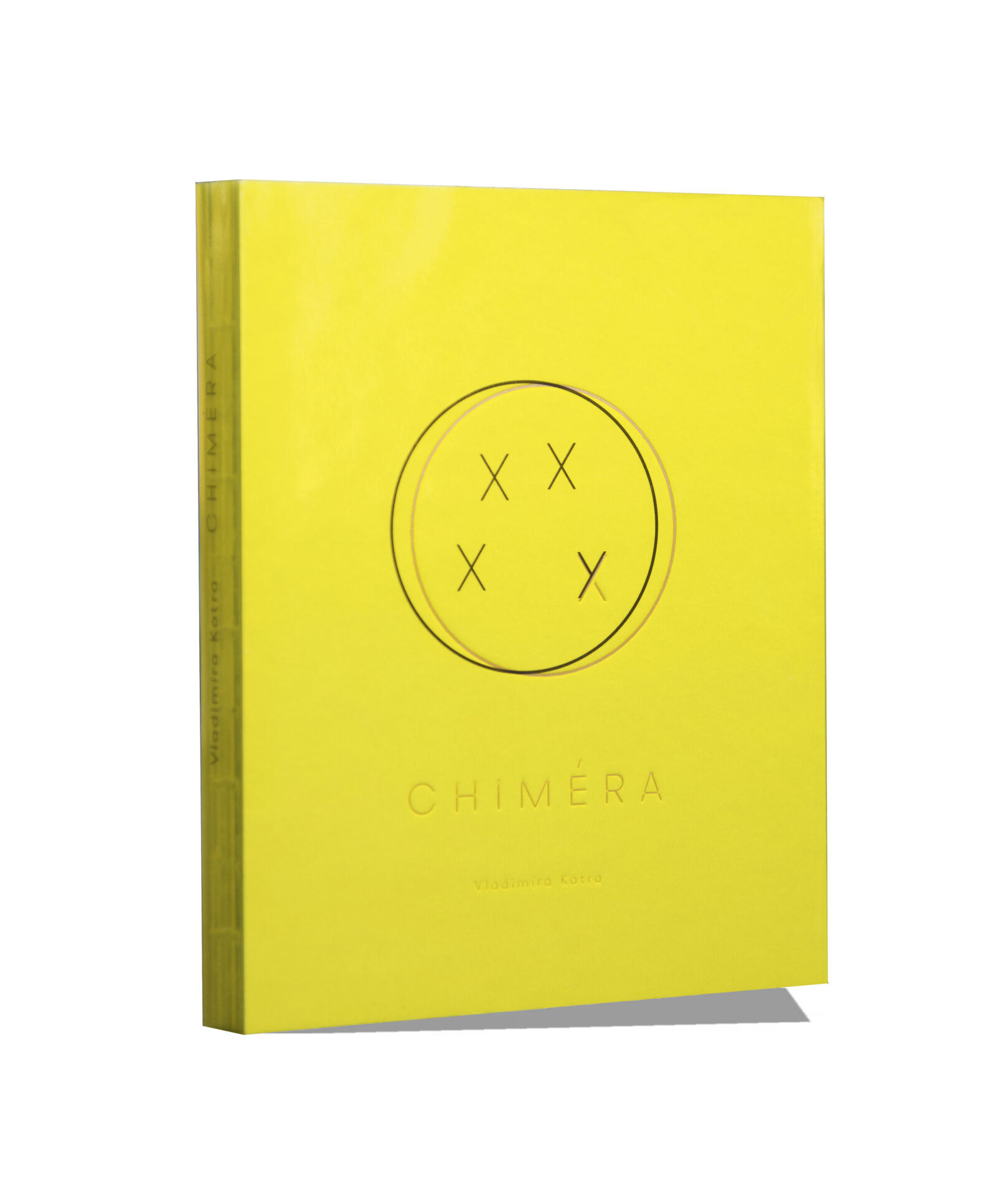

So, the whole project started with me asking and her agreeing and leaving me with a blank cheque. We started to see each other few times a month and I started to take time-lapse portraits in the same place and under the same lighting every two months, focusing on the bodily changes caused by the hormonal replacement therapy. I’ve started the project already knowing I want to turn it into a book because this project needed it. I knew it would be great to include a lot of different media such as her selfies because, in the beginning, she diligently documented each and every detail: how her hair has grown, the first time she painted her nails, the first time she went out as a woman… You could just feel the excitement. She kept a diary blog at the same time and shared her feelings about the transition abundantly on Facebook. That later proved to be rather challenging for friends who cared and still care about her. She was really enjoying the first six months of the changes and the elation of finally having found herself, believing that her misplaced identity was the constant source of unhappiness in her life. But after those six months, she started to painfully realize that she’ll never be a “perfect” woman, according to her, because she can never have a child. Those were hard times even for me because it was difficult to find words of solace even though the world is full of women unable to bear a child, which doesn’t make them any less of a woman. She subsequently started to suffer from really strong bouts of depression and to hate her new body, scrutinizing every detail, thinking she’ll never reach the image of her “ideal” woman; her looks were a source of disappointment to her. To me, she looked more beautiful and changed every day but I believe this is a transition phase probably all transgender people sadly go through.

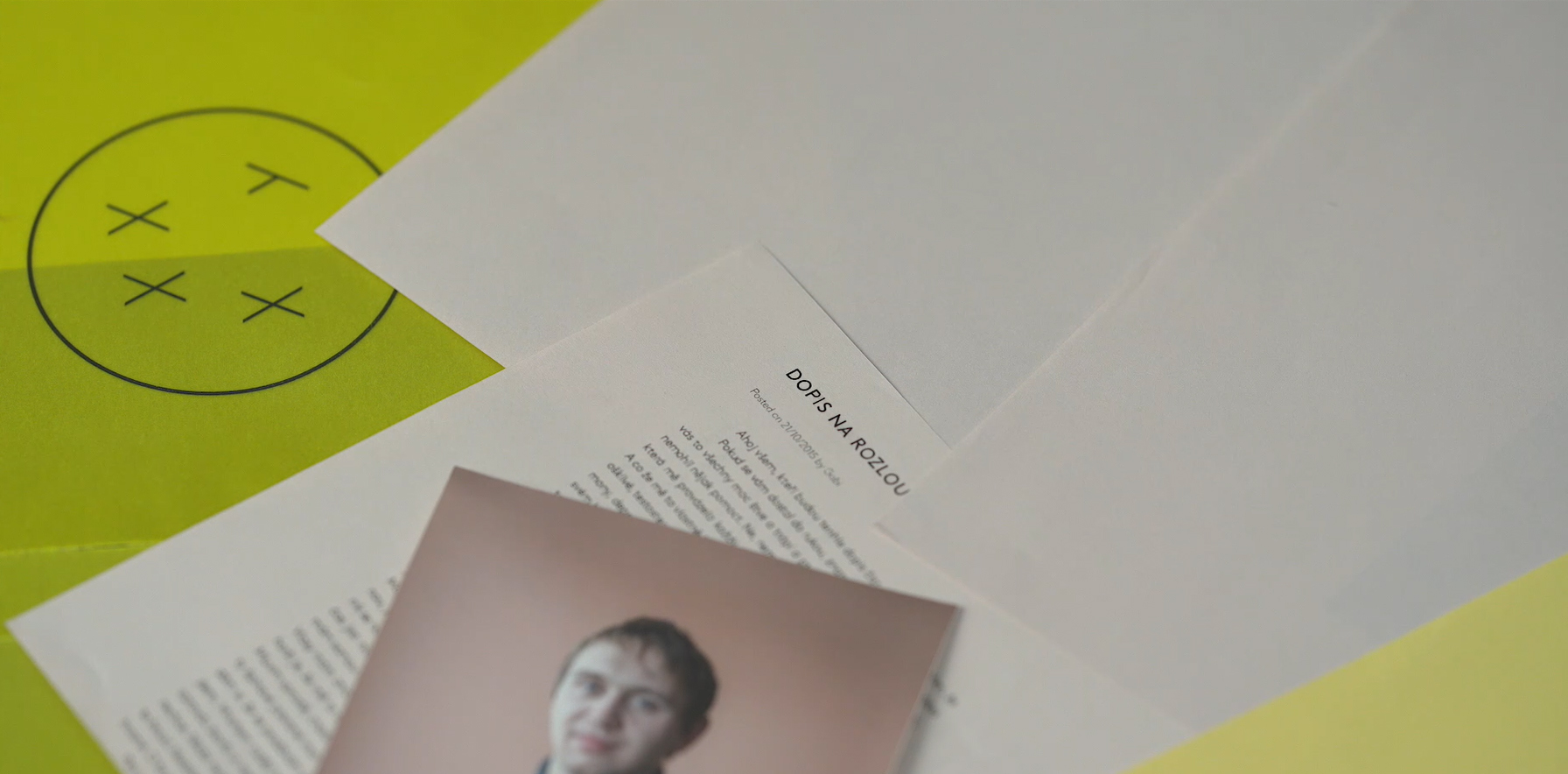

One November day, about a year after she realized she’s a woman, all this culminated with a goodbye letter posted to her Facebook. I’ve noticed it immediately after arriving at my work shift, shook off the shock and started sending people to all the places she could be. A colleague finally found her in her studio, badly messed up but alive and that’s all that mattered.

In one of your previous interviews, you said that the first photo exhibition and the book release itself was preceded by many negotiations with Gábi who changed her mind several times and didn’t want the photos published. How does she perceive the project now?

After that goodbye letter and all that followed, the relationship of Gábi, my then husband and I started to be quite tumultuous. Due to her high IQ, she never respected any therapist or psychologist and often felt not enough supported by her circle of friends. Regarding the two of us, this resulted in her constantly changing her mind about the photos and the exhibition – one day she wanted them published, the next she didn’t, which continued over several years but I have always tried to respect her decisions despite all the tense moments. Understandably, she didn’t mind me publishing her selfies but she wasn’t a fan of seeing our pictures from the onset of the transition, which triggered her dysphoria. About a year ago, she gave me the final permission to actually publish the book. In the book, I constantly highlight that it documents just the first and pivotal year of the transition and that she is now miles ahead of it five years later. So much that people who knew her “before” don’t recognize her and she’s living a new life, doing something she loves, which fulfils her and makes her content.

Did your relationship with Gábi change in the course of the one-year documentation and after five years since her transition? Are you still in touch?

Everything changed in those five years. Not only my relationship towards Gábi but also towards my then husband. We haven’t been in contact with Gábi for a long time but my ex-husband still is so I know a little bit about what she’s up to these days.

You’ve mentioned before that Gábi is not, according to you, a typical representative of the transgender or intersex community because her feelings of dissatisfaction and discomfort didn’t just stem from dysphoria and the assigned-male-at-birth identity crisis, but from the nature of Gábi herself. Do you still hope that your book could lend a helping hand to someone in a similar situation?

There was a moment I was reluctant to publish the book and was constantly ruminating over whether it can be hurtful to Gábi even though she gave me her permission. But then I went over all the texts, blog posts and photos included and saw how important it is for the book to come alive. That it might truly help someone facing a similar situation and give them a different outlook. And because Gábi is a really interesting person to look at and read about, alongside her great insights on being a lifelong outsider, there are many questions and contrasts in between the lines, which I mirrored in the photography styles I used. Especially, I would be glad if this book could help the general public to understand how difficult it is for people like Gábi. No one chooses to just transition deliberately, on a whim, as attention seeking. What these people must go through can be likened to a little hell and that is what I mainly wanted to show with the book. I wanted to zoom in on the feelings of a person who decided to transition so people could empathize. On the other hand, the Chiméra book is a rather niche artistic expression in a limited edition, I’m not naïve to think it could reach a large portion of the general public. It will mostly end up on photography enthusiasts’ shelves but they too can and will have prejudice and this book might challenge them.

Also, Gábi claims that, about two years into the transition and during a pre-op check-up, they discovered chimerism in her body. She apparently absorbed her twin in the womb, which means she’s carrying two distinct DNA patterns and a rudimentary uterus and other organs. At first, she wasn’t too happy to discover this but only because Czech healthcare doesn’t really know how to medically pigeonhole such individuals and she was worried about the progress of her transition. But all went well in the end and she took this as a confirmation of something she has felt for a long time.

Your project came to life in the Czech Republic. How open do you think is the Czech society towards such themes?

I think that Western society is more open towards these topics and Czechs need to step up their perception, especially outside of the capital, Prague. But I’m from Ostrava, the Czech Republic, and I was glad that when I showed the texts to my family, their reaction was pity and sympathy. I know Gábi wouldn’t be happy about that but I saw that was the thing that made them change their opinion on this topic and made them realize that similar people are only human, with all their human emotions, and that we need to help them instead of undermining them and mocking them with needless bureaucratic nonsense.

Did you register any reactions to your book/exhibition that surprised you?

I can’t really pinpoint the reaction to the book and the exhibition. People mostly commented on the visual style of the book and my approach to the topic, not the topic itself. We talked about the story and Gábi and her life in general. In the end, Gábi herself didn’t make it to the exhibition although she wanted to because she was still constantly changing her mind about it. Nowadays, I think she is finally at peace with the book and its publications, also because it was only about 300 pieces that were, according to her, taken home almost only by my “photographer friends”.

Do you plan on exploring a similar “documentary” line of work concerning gender and identity in the future?

I’m grateful that I got to get closer to the community and the world that surrounds it thanks to Gábi. Honestly, I’ve never given much thought to gender in general before I met her and she made me think about what being a woman means to me. It made me rethink various boxes I had in my head, even about self-determination. But still, I think five years of focus were enough for me and I want to photographically pursue entirely different themes in the future. All my projects are based on a momentary interest of mine, they need to stem from it, and I feel that I’ve fulfilled and exhausted the topics of gender and identity – meaning for me, personally, for now. I don’t think I will be back to it but one never knows. Some say it’s good to have a signature artistic style and aim but I’ve never really played along with that, as you can see in my portfolio.

Is there a question about Chiméra and working on it you would wish to answer but no one has asked it yet?

I would like to mention Gábi’s happiness. The book is centred around searching – for general happiness and satisfaction – and I think that Gábi found hers not only because of her transition and the realization that she’s a woman but because she also managed to come to terms with her temperament and personality. That’s my hidden message in the book: that no external influence, no other person, and no career or other successes can make us entirely happy and that the key to happiness almost always lies within us. Of course, Gábi did a huge step towards her happiness by realizing and acting upon this pivotal realization but that wasn’t the thing that ultimately made her happy with her life. She found that in an amazing job that fulfils her and in realizing her talents and putting them to work.

BIO / Vladimíra Kotra finished her Master’s Degree (June 2018) in Creative Photography at the Institute of Creative Photography at Silesian University in Opava, Czech Republic. Her final project at school was a photo book called Chiméra (Chimera), which deals with the complicated state of mind of a human being transitioning from a man to a woman. Kotra combined photography with her model’s Facebook statuses, smartphone selfies, blog posts, etc. For this project, she was shortlisted in the Portrait category of the 2017 Czech Press Photo awards. The Chimera dummy book was finished in 2018. The Kassel Dummy Book Award, Self Publish Riga and Singapore International Photography Festival shortlisted the Chiméra dummy book among the Best Photo Books of 2018 thanks to which it made rounds at various European photography festivals. Chiméra was finally published and debuted in July 2020 in a limited and signed edition of 60 English and 240 Czech copies.

For more of her work and to order the book, visit Kotra’s webpage: www.vladimirakotra.cz

Interview & Translation / Franiška Blažková