In my mind, I always thought hard work, sweat on my forehead, and skin peeled on my hands with clay under my nails that cannot be removed with the most precise manicure would always feed me. I’ve never longed for a life in a large community where I would have a nicely padded ergonomic chair to process and distribute data. I’ve been through quite a few chairs, and this experience has led me to my final decisions: asceticism and working the land.

I did not have a deep relationship to my chosen profession, but I always had a friendly respect for it. Our friendship had ambivalent parameters and was adapted to the final volume of harvest I was able to produce.

The shifting seasons in solitude had formed a strong thread in me, but in places it was not enough to bandage the bloody calluses. I have always taken meticulous care of my exterior. During the solstice, I skipped every other serving of hops so I wouldn’t exceed my daily caloric intake. Despite my best efforts, the hard work in the field was taking a greater toll each passing year, and the long fingers with soft pads transformed into massive red tubes. Apart from the aesthetic illusions I had long ago given up, even the chestnut bath for my heat-weary limbs was no longer working.

That’s why I see robotized agrarian assistance as an essential part of my profession. There have been several assistants, and I have developed a deep relationship with each of them by accompanying them with daily rituals. For the readers of this report, I find it unnecessary to delve into my personal preferences, but I will informatively describe them one by one.

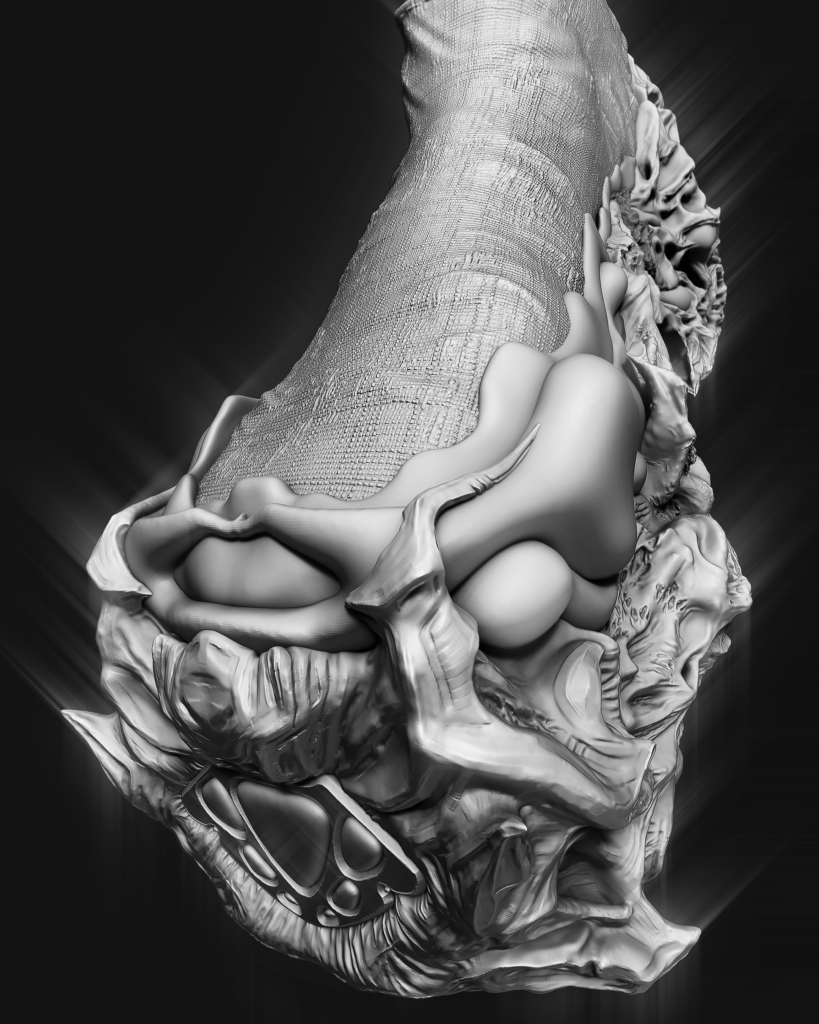

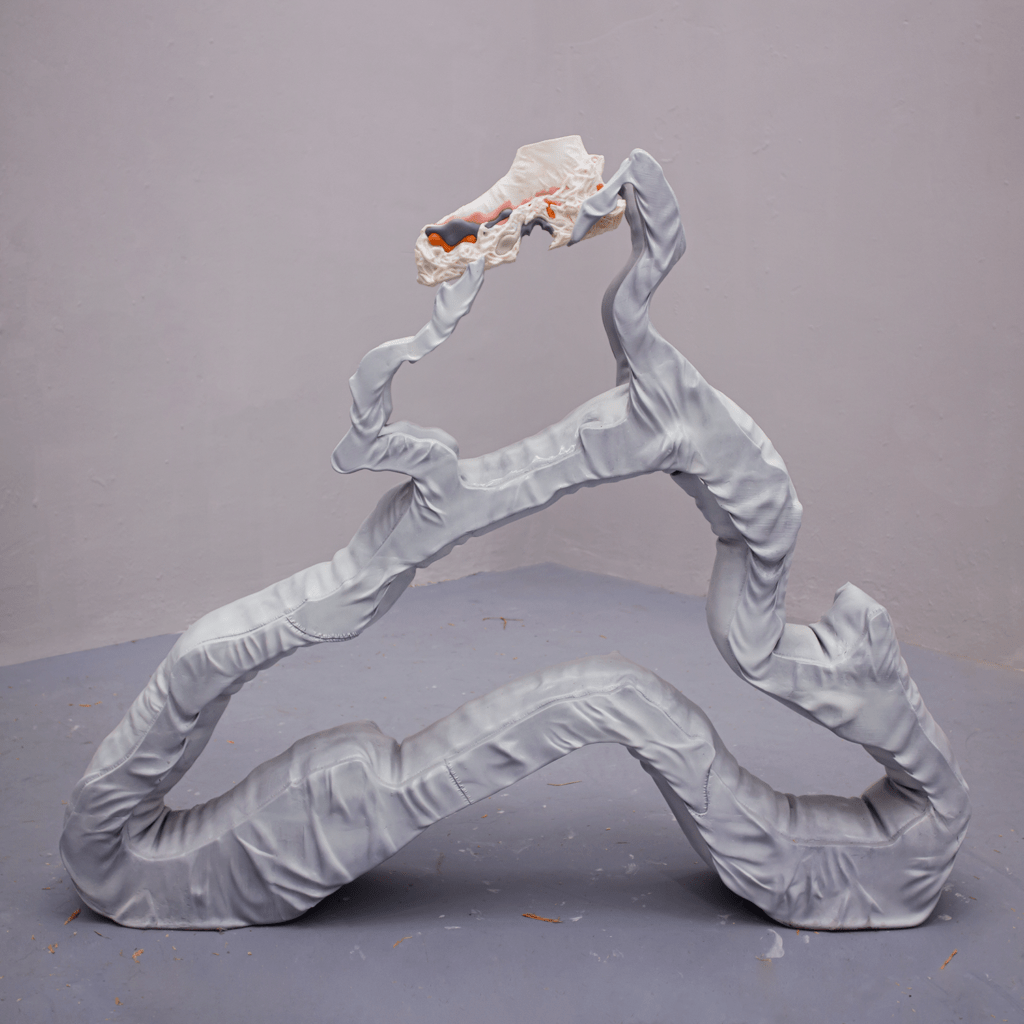

The first of the performers was the support extender, who fixed himself to my body every morning and then assisted any movements of my torso. The unisex corset would always adjust to the wearer regardless of their physical parameters, which came in handy when the volumes of crops changed.

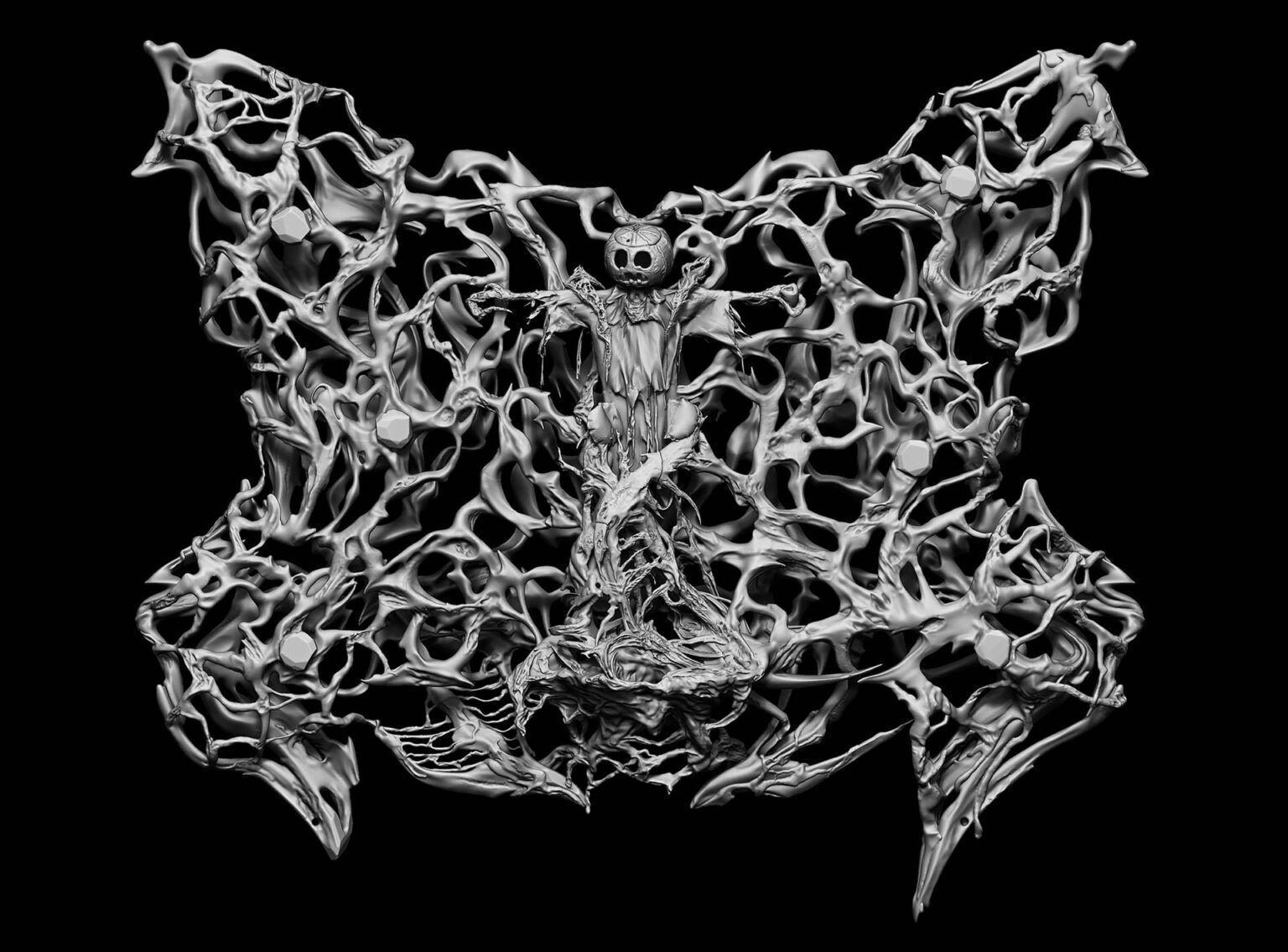

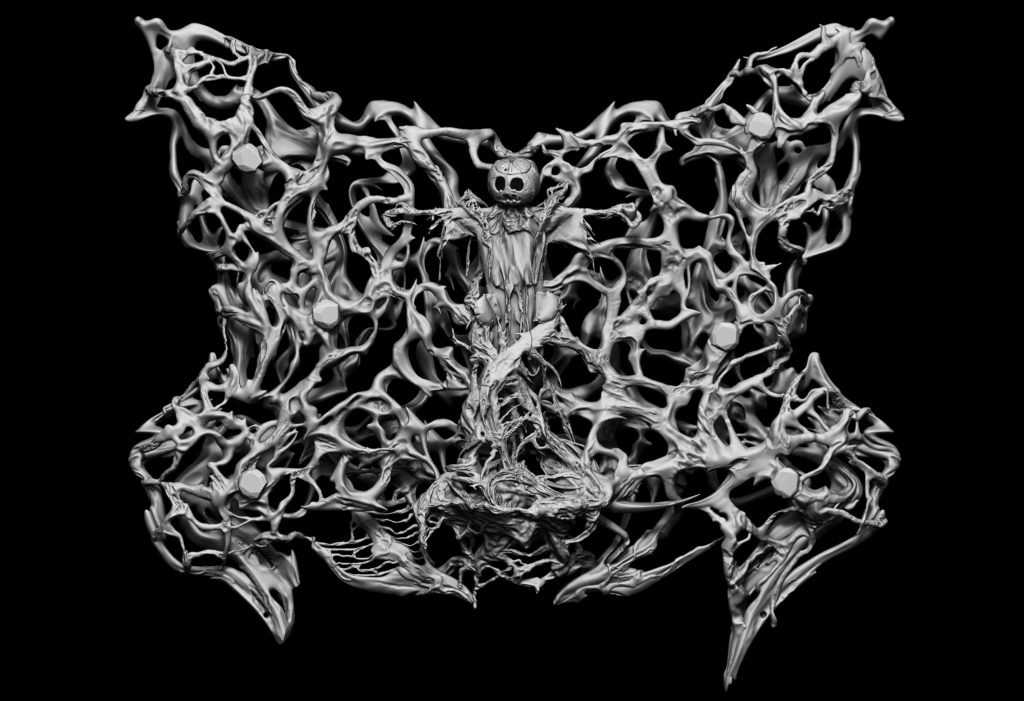

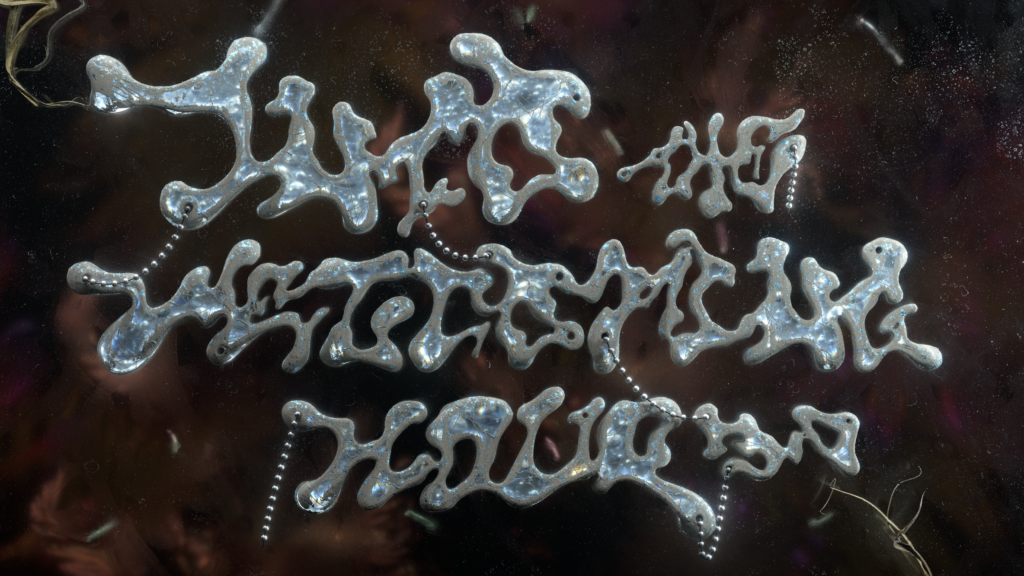

Another fashion accessory of mine were the ploughman’s boots which, when taken off, had an automatic mode. I’ve also used this feature in recreational goals in the form of mini races in tillage, which I usually lost and turned the shoes off halfway through. Although I never accepted the losses, I usually agreed to a draw so as not to be seen as a complete hoarder in the eyes of the referee. The verdict and the final score was delivered silently and without movement, by mere observation, by the field scarecrow.

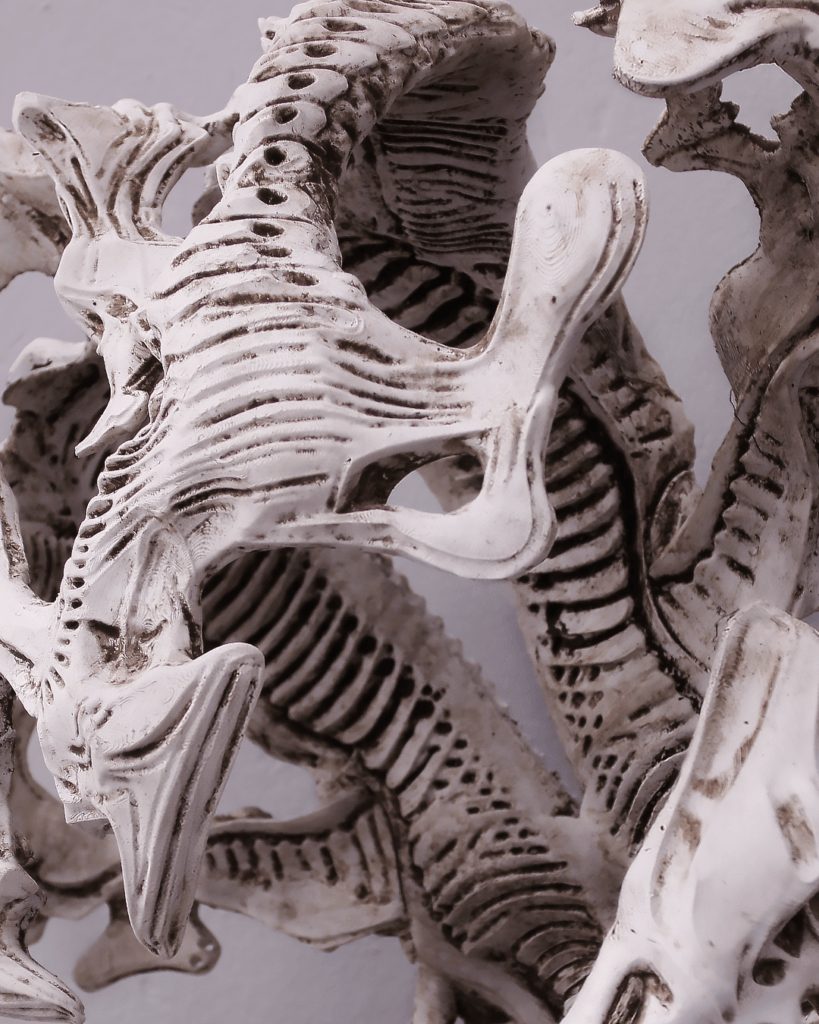

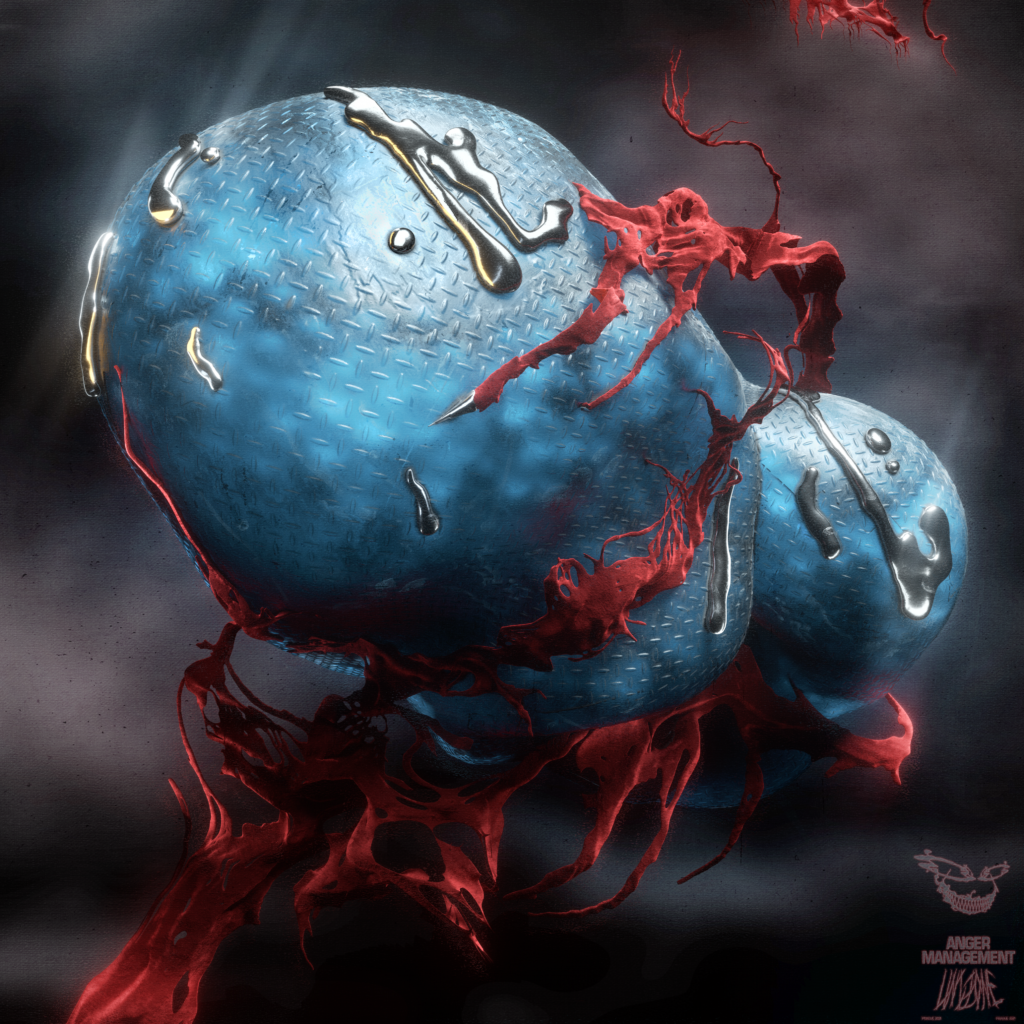

It was an outdated technology from my father’s youth, which I managed to restore after several sessions. Its primary function was to observe climatic variations and then adjust the programmed delivery of nutrients. Beneath the surface of my humble field there lies an elaborate system of fibers visually resembling the roots of a tall oak tree. The mute observer thus becomes not only a visually central figure, but also a place from which energy for the vegetation flows.

Its original function of scaring animals away became the responsibility of an integrated sound chip with a small internal memory. When the sensors detected an animal organism that did not match my proportions, the first phrase phase was triggered with screams that chased animals away. The second phase triggered an annoying alarm designed to wake me up if the animal remained in the field.

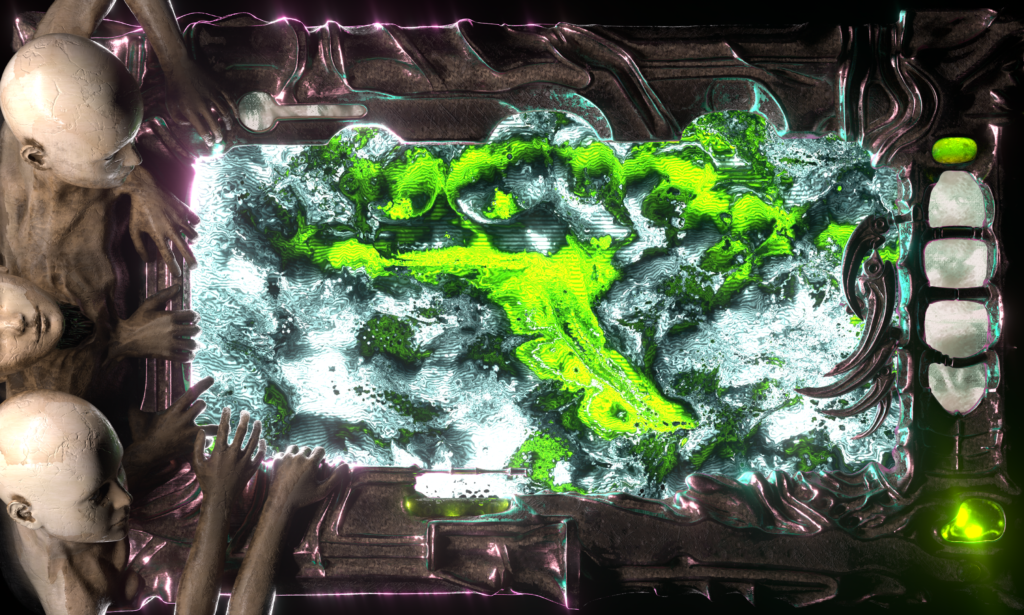

For a quarter of a year, I have been living with my agrarian ecosystem, harvesting a summer crop of red sun-soaked tomatoes. My eyes were filled with twinkles from the sun. Every time I reached for another tomato, in addition to the spots I registered the silhouettes of my co-workers.

- 52 tomatoes

It echoed behind me, and the wave stirred each of my receptors. With acrobatic precision I executed a quick spin landing on my rear in soft dirt mixed with tomato juice. The freshly stirred compote pleasantly hydrated me. I saw clouds floating by and an internal moment of calm told me I wanted to stay in that tub.

- 52 tomatoes

- 15:34

The sound came again, the newly added information leading me to leave the bath. Picking myself up, I did a quick count of the number of tomatoes in the basket and went to the scarecrow.

- There’s 51, you got the score wrong.

It was in no hurry to answer, nor did I expect it to.

- 52 tomatoes

- 15:41

- Air temperature rising

The ground vibrated and lifted 10 centimeters with me from where I stood. Its artificial stance, with its face deathly fixed, irritated me immensely. I looked into the empty holes that were supposed to represent eyes. The liquefied dew in its hollow head danced in the sunlight along with my reflection. The reflection irritated me too. My mimicry was stiff, silent, trying to mimic its static, sculpted grin.

- 51 tomatoes, there are 51 tomatoes in the basket. There won’t be one more today.

Scarecrow

- 52 tomatoes

- 15:50

- The air temperature is rising.

- The humidity in the air is decreasing.

An uncontrollable whiteness ran through my entire body. I tore wire after wire from its hulls with a delight I had not felt during a single harvest in this field. When I felt the cold touch metal walls of its interior I left the rhythmic seizure and sat in the clay settled with a wide, artfully colored spectrum. The clouds continued on, the wires hydrating only the inside.

Then, I returned to my hut, calm, feeling the earth tremble steadily on the way; perhaps I was too long. I leave this report for the next ascetic and go south to the sea. I hope the old nets are standing strong, it’s been a long time since I felt a sea breeze.

The ground vibrated and lifted 10 centimeters with me from where I stood. Its artificial stance, with its face deathly fixed, irritated me immensely. I looked into the empty holes that were supposed to represent eyes. The liquefied dew in its hollow head danced in the sunlight along with my reflection. The reflection irritated me too. My mimicry was stiff, silent, trying to mimic its static, sculpted grin.

- 51 tomatoes, there are 51 tomatoes in the basket. There won’t be one more today.

Scarecrow

- 52 tomatoes

- 15:50

- The air temperature is rising.

- The humidity in the air is decreasing.